1 Introduction

The V&A identifies its audience in terms of six definitions of visitor type, which are not mutually exclusive. They are: independent adults, students, families, organised groups, schools and adults from the Creative Industries (CI). Whilst the V&A has a long association, dating back to its foundation, of working with artists and craftspeople, it is only within the last decade that this latter group of visitors has been grouped together under a particular label. Developing an agreed definition of the CI as part of the visitor segmentation post-opening of the British Galleries in 2001 had been somewhat of a struggle, but by 2004 the Museum had a set of six audience definitions, including one for the CI. However, this was an ‘internal’ definition, so to speak, and during the last decade the nature of the CI has become something debated far wider than within the V&A as an institution. The introduction of the term ‘creative industries’ in government language in the late 1990s was the beginning of an attempt to bring unity to a fragmented selection of industries identified as contributing significantly to the British economy. Since then, there have been significant developments in policy aimed at nurturing, benefiting from, and ensuring the continued growth and success of, the Creative Industries. Responsibility for this sector lies nominally within the Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), but both the Department for Skills and Education (DfES)1 and the Department for Trade and Industry (DTI)2 have launched initiatives and commissioned reports investigating the growth of the creative industries sector. The Cox Report, a review of creativity and design in UK business, was published in December 2005.3 One of the objectives set out in the V&A’s 2007–2012 Strategic Plan is, ‘to promote, support and develop the UK creative economy by inspiring designers and makers and by stimulating enjoyment and appreciation of design’.4

In response to this, and as part of a long-term programme to revisit the definitions of its six visitor categories, in 2006 the Head of Gallery Interpretation, Evaluation and Resources at the V&A launched a research project aiming to redefine the V&A’s audience segmentation description of the CI. After an initial literature review was conducted, data was collected over the course of nine months and consisted of three phases:

1. In-depth ethnographic interviews and observation with twelve participants from a range of CI professions:

- Jewellery

- Ceramics

- Textiles

- Film production

- Architecture

- Web design

- Theatre production

- Public relations

- Auctioneering

- Publishing

2. Guided discussion and accompanied visit to the V&A with three subjects representing three different CI professions:

- Ceramics

- Film production

- Architecture

3. On-line survey of eighty-one participants randomly sampled from fourteen CI professions:

- Architecture

- Advertising

- Audio-visual and interactive media

- Cultural heritage

- Cultural tourism

- Design

- Fashion

- Museums, libraries, archives

- Music

- Publishing

- TV and radio

- Visual arts

- Performing arts

The findings from this research project were extensive and complex. This short article will present one aspect only of the findings, which is an exploration of the appropriateness or otherwise of considering the CI in terms of a community of practice. Within the terms of the research, it was necessary to establish this before going on to consider the findings in terms of the nature of the relationship between the CI and the V&A. These latter findings will be presented in a further paper to be submitted to the V&A journal at a future date.

2 Defining the Creative Industries

It was first necessary to identify current definitions for the CI in a wider context external to the Museum. The literature review looked at government publications and reports related to the CI, and explored a number of agencies and forums that have been set up to service the CI.

There were several findings with direct implications for V&A thinking about CI visitors. The first was that they include those not actually involved in a creative occupation themselves (e.g. an accountant at a design agency) and those involved in a creative occupation but not actually working in a creative industry (e.g. an in-house designer working for a city firm). This type of definition dates back to early thinking about the CI, such as the 1998 report ‘Creative Britain’.5

The second finding was the inclusion, by agencies such as the Creative Industries Task Force,6 of industries where creative processes are utilised. Therefore the CI in their broadest spectrum are considered to consist not just of’core’ industries with obvious creative output but also industries employing ‘creative strategies’. These are termed ‘related’ industries and activities and are included in all government strategies for the CI. These first two findings can be said to form a spectrum of ‘creative activity’ ranging across a variety of type and depth of engagement with creative practice in people’s work.

The third significant finding was that, despite much discussion about the potential educational and social benefits to be gained from nurturing the CI in the UK, ultimately economic benefit to the UK is the primary outcome Government Departments responsible for CI initiatives are interested in, as emphasised in the 2006 report by the Entrepreneurship and Skills Task Group (ESTG).7

Finally, and in notable contrast, it was found that that many elements within the CI sector do not necessarily label themselves as such. The literature review looked at current magazines and journals associated with sectors identified under CI, such as “Blueprint”, “Crafts”, “Design History Newsletter” and “Frieze”, and found that there was little or no reference to the CI. It also is worth noting that the Office of National Statistics, in a recent publication of figures of the UK workforce segmented by industry, does not have a separate segment for the Creative Industries.8

The broad ‘creative activity spectrum’ identified has attendant issues for anyone interested in working with the CI, and particularly for this research project, because of the enormous variation of scope and activity within the unit of study. This makes it a challenging sector in terms of visitor profiling for the V&A.

3 Communities of Practice

Given the issues in defining the CI, the researchers used Wenger and Lave’s ‘Communities of Practice’ methodology as a framework to define the research.9 ‘Communities of Practice’ is grounded in sociological theory of practical knowledge, and pedagogical theories of situated and social learning. It aims to identify groups of people bound together through knowledge, and is based on a definition of knowledge that includes tacit knowledge that is shared informally through human interaction processes such as storytelling, conversation and coaching or mentoring. Their greatest value lies in intangible outcomes, such as the relationships they build among people, the sense of belonging they create, the spirit of inquiry they generate, and the professional confidence and identity they confer to their members.10

However, ‘Communities of Practice’ also acknowledges that this shared knowledge is dynamic: constantly changed, transformed and updated through these same processes. Members spend little time on searching for solutions to short-term problems because they can get access to help or immediate solutions quickly through their community or communities. Members are also more likely to take risks as they feel they have back up and support from the community of practice. This has the intangible outcome of a sense of trust, which in turn has a tangible outcome of an increased ability to innovate.

There are three indicators of structure for a community of practice:

- A domain of knowledge with a defined set of issues, which creates common ground and a sense of common identity. The domain also inspires contribution and participation. However, it requires participants to know its boundaries, in order for members to be able to present ideas and pursue common activities.

- A community that creates a social context for learning. The community interacts and fosters relationships based on respect and trust. An effective community of practice handles dissent productively. Members are able to share ideas, expose ignorance and ask difficult questions. This interaction fosters learning and also a sense of belonging and commitment. However, members remain individual not homogenous, and develop their own specialities and styles.

- A practice consisting of a framework of shared ideas, tools, information, language, stories and documents. This forms the basic knowledge of the community that all members share and from which development and innovation can spring.11

4 Findings: The Creative Industries as a Community of Practice

4.1 The creative activity spectrum.

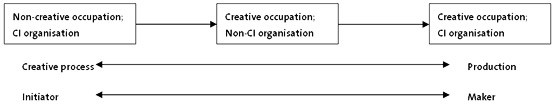

The spectrum of occupation within the CI can be said to look like this:

4.2 The Domain, Community, and Practice across the Creative Activity Spectrum.

Exploring potential indicators of a domain indicating a community of practice, the following shared issues were found to be consistent within the CI:

- The design challenge: pushing boundaries in all areas of practice, e.g. working with new materials such as casting glass in microwaves, ‘using new technologies and integrating them into the craft process’ (Jeweller).

- The business environment: participants made very clear choices about assuring at least a base level of income. This was perhaps not their ideal practice, but freed them in their other time to follow their own practice, as ‘the idea really is that we can say no to jobs that we don’t want to do rather than just having to take everything on’ (Architect); the practical motivation for this work did not mean they would compromise on quality.

- Validation through peer and commercial success. Participants were very concerned about making the right product for the right audience.

- Validation through ‘client’ feedback. This was particularly so at the initiator end of the spectrum, as for example an auction house director felt ‘well we are seeing it from the sales but we get good feedback, we have had excellent feedback from things but the great thing about (x) is that you can see whether something is working, you can get a good feel for if something’s working from the results of the sales’.

- Personal ambition: the need to constantly push further. The jeweller disciplined herself to do one collection per year during the summer to ‘prove to the outside world that I can still do it’ (Jeweller).

- Risk taking and innovation: a key motivation and widely recognised indicator of creativity across the spectrum, which encouraged innovation because ‘you don’t hit brick walls because probably our sheer audacity is doing something that people haven’t thought of doing before’ (Publisher).

- Enjoying problem solving, rather than seeing problems as blocks to success. A jeweller highly enjoyed and valued this, saying ‘it comes very naturally to me, problem solving on the spot’.

- For a majority of makers, but significantly less so for initiators, an academic research element and formal education was integral to the domain. A textiles designer particularly emphasised that ‘for me educating is the consequence of the experience as a designer and I think that if I stop designing … I’m not saying that I won’t have stuff to give, but in a way that was the process for how I came to education … I think it’s a two-way flow and I think that has to keep going, if you’re going to be effective’.

- Quality control: performed informally through peer-review and self-discipline.

The above are issues that work well as a shared domain within the communities of practice framework, and during the data collection, particularly in-depth interviews, participants themselves also identified some of these indicators as shared across different creative disciplines. A publisher articulated this as being creative skill rather than specifically discipline-related: ‘if you have the medium then you apply that medium, that skill to whatever you are supposed to be creating but the creation process I think is equal across the board in the creative world’.

This research found that nature of the CI domain, as identified through the indicators described above, makes this community of practice more than a set of relationships and goes some way to giving it an agreed identity. This identity fosters commitment to care for the domain, and makes the CI a community of practice, more than a collection of individuals with an informal communication network. However, it was fragile and there was constant flux within this domain. For some participants this was a source of anxiety as well as challenge, because ‘it’s an industry that changes constantly, it’s very easy to fall behind and not be aware of current activities that are part of the working environment’ (Textiles designer).

Looking at the nature of the ‘community’ within the CI, this research found that the network was primarily how people across the entire spectrum tried out new ideas, and tested them. A publisher described ‘you know everybody comes up with bad ideas but luckily there is a good filtering process. The more people you talk to, you can weed all those out before they get any further and cost a lot in development’. Within the community, creativity itself was described predominantly in terms of a process, that ‘creativity is the thought process needed to produce or provide’ an identified outcome (Jeweller). Notably, at the maker end of the spectrum, people defined themselves as academics and had planned to do so, as a jeweller recalled: ‘I had applied also already for the RCA because I wanted to become a teacher really, that was always my plan’. This was part of a desire to pass on skills and intangible knowledge gathered during experience, not just in terms of creative skills but also business skills, considered vital: ‘I wanted to feed that back, to channel it back in to younger people to fast-track their experiences in a lot of ways through the experience that I’d had and transmitting those to someone, so that they didn’t have to go through the same experience to an extent. That they could accumulate that, based on someone else’s experience, that had gone before’ (Textiles designer).

Often, the aim of working in the CI was a vocation the participant was aware of from an early age, for example a theatre director who said ‘I have a feeling that I have been working towards it all my life’. Surprisingly, being creative was actually seen as only a small part of the criteria for professional success. However, it was the kernel that made all the difference to their enjoyment of work, as ‘it’s the idea to go back and be able to talk about ideas and spend hours in a whole day talking to people about ideas and process and values and that’s a great luxury’ (Architect). It is this luxury that allowed participants to innovate.

Mentors played an important role, even during relatively unfocussed times of early professional development. This ranged from sensing a feeling of empathy with like-minded people, to meeting someone particularly inspiring and nurturing. A publisher described: ‘I was picked up by a brilliant Dutch designer from Pentagram. He liked my attitude, I think it was very similar to his and really he gave me an apprenticeship which I am so grateful for’.

Finally, collaboration with others was critical as a way of participants finding their path in the community. Across the data, people described themselves as part of a chain within which they maintained their individual aspect.

The community factor within a community of practice should be essentially a network of relationships that allows exchange of ideas and risk-taking within a safe, non-judgemental environment. The network of relationships in the CI found amongst participants was based on five common elements: ideas, process, experience, innovation, and collaboration. This gives confidence to its members. Members are able to take risks and expose themselves to failure because there is no ‘hierarchy’ within the community.

The research found that the community network is well established within individual disciplines, but less so across the whole Creative Activity Spectrum. The shared issues identified above are not specific enough to coalesce to form a domain that works across differing disciplines within the community. The lack of these defined boundaries, affecting the community network, is possibly an issue that contributes to a lack of self-identification of the CI with the UK Government concept of CI.

‘Practice’, the third indicator of a community of practice, was important for the CI across the spectrum. It was the area where the research identified the most unifying factors, for example the huge proportion of participants who read The Guardian (82.9% of on-line participants). Within practice, the notion of a spectrum of process and practice came through strongly. However, it was also where the most complex debate around the nature of creativity itself occurred. Many participants spent a long time in discussion through the various data collection methods considering creativity, but one jeweller summarised the open-ended nature of the debate by saying ‘creativity is easy to assume, but not so to define. The concept is wide open depending on its context and it would be unwise to be so reductive’.

An issue that came up many times was the importance not just of design and practical skills, but also of understanding how to negotiate the field. The need to ‘understand the professional, the profession and your role within the profession’ (Textiles designer) was critical to people’s sense of professional identity. A significant skill was the ability to see a concept through to production, requiring project management and people skills. Being able to foster and maintain an original concept through this was seen to be the ultimate in definitions of creativity. ‘For it [the final output] to resemble what you had in mind in the first place is another great leap’ (Architect).

This was reflected in the workplaces that were visited as part of the ethnographic data collection. For the most part open plan, sometimes with specific work areas allocated to tasks rather than specific people, all were extremely well organised and had areas where the ‘bones’ of projects being worked on were exposed. For example, the textiles designer was very clear about separation between what he called ‘the workplace’, which is the commercial production environment for textiles, and the ‘educational environment’ which is for teaching, even though physically there may not have been a difference to the untutored eye. All participants talked about cycles of working practice they had developed to ensure multiple project management. An auction house Director described himself almost as the eye of the storm: ‘My job is to make sure that it all comes together in a timely fashion and I also work to pull the images together so I can let all these people know, certainly from the creative side of things’.

Participants felt that their chosen area of design was a matter of application rather than vocation, although working generally in the CI field was a vocation. A ceramicist described herself as a visual artist who predominantly works in clay; a textiles designer had started off training as a ceramicist. This was not just a matter of the type of output but applying creativity across a whole range of skills, as a theatre director described: ‘certainly I would advocate that now people are much more, you know you’re not trained just to be an actress, just to be this, just to be that, and that there is something creative entrepreneur, cultural entrepreneur, a real subject … you have a much broader view of what you could do’.

Participants were not necessarily specifically formally trained but nearly all mentioned informal continuing development (90.8% of on-line participants). Notably, at the maker end of the creative activity spectrum, participants had been engaging with their creative practice from a very early age. By the time they were ‘mid-career’ professionals they could easily have been working in various creative disciplines for twenty-five years. This meant that students were already viewed as professionals even by their tutors.

Collaboration in the community was about working as an individual within a collective, with ‘like-minded people’ rather than in the same discipline. The need to retain individuality was directly related to professional ego, as a textiles designer described: ‘I’m happy to work like that in my own design field and then go out and discuss but actually the design process is a quite personal one’. However, in contrast to feelings about collaboration, ambition and self-promotion came through strongly in terms of self-discipline. This combination of seemingly conflicting factors resulted in a key indicator of the CI community of practice, which was that all the participants were very adept at analysing their own strengths and weaknesses and using collaboration to address them. They were therefore good at finding people with the right skills and knowledge to help them achieve the ‘vision’ of their practice. A publisher described using his network for this: ‘I like people who come up and can be incredibly resourceful, can realise something while still being really resourceful and that is why I like to employ people with a lot of contacts who have worked in and around the creative field’.

It seemed that the primary shared feature of practice was the interest in process rather than product. Whilst people were interested in following their own practice, and organised their work commercially to enable that, they also liked competitions, which they felt set boundaries that challenged their practice and therefore produced better work.

5 Conclusion

This research showed that the Creative Industries closely resemble a community of practice. A notion of a spectrum of creative activity from initiators to makers emerged, and elements within the domain, community and practice varied slightly according to where participants sat on the spectrum. Across the whole spectrum, but noticeably with makers, the idea of creative industry was seen as something applicable across many disciplines. There was very strong self-identification for makers from an early age, which was not necessarily related to the stage of formal training they may have participated in. This was in part because creativity was seen much more as a process than a product, but also because people were very aware of their own strengths and weaknesses, and viewed collaboration as key to addressing them. This was balanced with an awareness of their own individual skill and unique selling points. Informal recommendation and word of mouth led to the most successful collaboration. Contrary to a generalised view of people who are ‘creative’, commercial success was more important than commonly assumed.

The creative activity spectrum identified in the research can be thought of as relating to the intellectual property of creative process, as well as to creative production. Significantly, the former can happen without a notably ‘creative’ output, but with a notably creative outcome, which is what the DCMS was particularly interested in cultivating to encourage economic success.

According to Wenger, the most successful communities of practice thrive where the goals and needs of an organisation intersect with the passions and aspirations of participants. If the domain of a community fails to inspire its members, the community will flounder.12 However, in this case the domain of shared issues was the weakest of the three indicators. The community was strong but with fuzzy boundaries, and the practice was most defined. For the V&A, this means that it is extremely challenging to nurture a relationship between the CI and the Museum which both contributes to V&A objectives and could also be proven to contribute to Government objectives. Furthermore, and most challenging for the V&A, is the great difference between Government thinking about the CI and thinking within those industries themselves. However, the benefits of the V&A considering the CI as a community of practice is in the potential the Museum could have to contribute not only to the knowledge management of the CI, the domain, but also to the practice that applies to this knowledge management.

Endnotes

-

As of 28 June 2007 this Department no longer exists and responsibility for formal education has been split across two Government Departments: the Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF) and the Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills (DIUS). ↩︎

-

As above, from June 2007 this Department has been disbanded and is now called the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (DBERR). ↩︎

-

Cox, G.S. The Cox Report: Creativity in business 2005 [cited 2007 15 March 2007]. ↩︎

-

V&A Strategic Plan 2007-2012, p.18 ↩︎

-

Authored by the then Secretary of State for the newly created Department of Culture, Media and Sport, Chris Smith. This report specifically identified the role of Government in bringing disparate elements of organisations and industries involved in creative production together, and nurturing it for economic, educational and social benefit to the UK. ↩︎

-

This was set up by Chris Smith (see note no. 5) to launch inquiries into identified ‘creative industries’ in order to make recommendations for steps the UK Government could take to aid productivity. For example, the Creative Industries Task Force Inquiry into the Internet, published June 2000. ↩︎

-

This is part of the DCMS Industries Education Forum. The report identified the CI as the fastest growing sector currently in the UK. ↩︎

-

UK Labour Market Statistics, ONS December 2007 ↩︎

-

Wenger, Etienne. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, 1999. Lave, Jean. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, 1991. ↩︎

-

Wenger, Etienne et al. Cultivating Communities of Practice. Boston, 2002. ↩︎

-

Wenger, Etienne et al. Cultivating Communities of Practice. Boston, 2002. ↩︎

-

Wenger, Etienne et al. Cultivating Communities of Practice. Boston, 2002. ↩︎