Abstract

This article investigates a 19th-century panel worked in the demanding technique of ‘intarsia patchwork’ that overturns our assumptions about patchwork as a craft practiced by female amateurs, used to decorate the house and to reinforce emotional ties. The panel forms part of a group of patchworks made by male professionals and exhibited for personal profit, and to promote social causes such as Temperance and Electoral Reform.

This small panel of ‘intarsia patchwork’ (fig. 1) is evidence of a tradition of patchwork made by male professionals and exhibited in public for profit. It highlights divisions between working-class craftspeople and middle-class critics over the definition of ‘art’ at the Great Exhibition of 1851. It reminds us that what seem to be individualistic artefacts were understood by their original viewers as part of continuing technical traditions and of contemporary visual culture.

The panel, measuring 43cm by 46cm, has a 23cm by 27cm central image of a farmyard, with a man in a red waistcoat milking a cow in the company of another farm worker, horses, pigs, geese and chickens. The shapes of the men, livestock, and farm buildings are executed in wool fabric, with details of foliage and features highlighted with silk embroidery stitches. This scene is contained in a frame of red wool with a scrolled motif outlined in silk chain-stitch.1 The rather naive depictions of animals and men were worked in the demanding technique of intarsia patchwork. This technique, also known as ‘cloth intarsia’, ‘mosaic needlework’, ‘inlaid patchwork’, ‘inlay patchwork’ and ‘stitched inlay’, involves cutting motifs out of wool cloth and stitching them directly to each other with no seam allowances and no backing fabric.2 On this panel, details like the spots on the cow have been inserted into holes cut in the fabric and oversewn to hold them in place, so that the finished surface is flat rather than raised as it would be with appliqué.

Intarsia patchwork is only possible with wool fabric that has been felted so that it does not fray, with a surface nap that can hide stitches worked from behind.3 These conditions were fulfilled by the wool broadcloth used for high-quality tailoring in the early 19th century, and the fabrics used in the panel are similar to those in gentlemen’s coats or army officers’ tunics. Professional tailors were expected to hand-sew wool fabric with invisible, perfectly flat seams. Tailoring manuals advised working with seam allowances of 2mm for closely fitting garments. So the panel could have been worked by a tailor demonstrating his sewing skills, and his thriftiness in using fabric scraps.

Intarsia patchwork has been known in Europe since the early 15th century, and was produced in 18th-century Prussia and Saxony and in Britain from the 1830s to the 1880s. However this technique, especially when made by male professionals, has been hard to assimilate into a narrative of quilt history based on cotton patchworks made by women, and was mentioned only briefly in seminal texts such as Averil Colby’s Patchwork and Barbara Morris’ Victorian Embroidery.4 The first discussion of British intarsia patchworks as a group was by Margaret Swain, who in Figures on Fabric identified the sources of many of the images used. Janet Rae in Quilts of the British Isles discussed intarsia patchwork as the product of working-class men from Scotland and Wales.5 My own earlier research examined the links between British and European intarsia patchworks, and between some of the images used and the visual culture of Radical politics.6

Intarsia patchworks were not fully integrated into British and European quilt history until 2009–10, when they were displayed in two groundbreaking exhibitions.

Quilts 1700–2010, Hidden Histories, Untold Stories (Sue Prichard (curator), London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2010) showed them as part of a survey that included patchworks with figurative and political scenes made by 19th century women and military patchworks made by men from soldiers’ uniform fabrics. Catalogue articles by Linda Parry, Jenny Lister and Jacqueline Riding brought out the ways in which patchwork and quilting have been used to display the makers’ knowledge of design trends and of current social issues, as well as their needlework skills.7 There was also a recognition of the role of patchwork as therapy, from Newgate prison in 1821, through the military camps and hospitals of the 1850s, to the Fine Cell Work Project at Wandsworth prison today.8

Inlaid Patchwork in Europe from 1500 to the Present (Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow (curator), Berlin: Museum Europäischer Kulturen, 2009–10) was the result of a thirty-year research project that published details of over 70 surviving examples of the technique, and exhibited over 50. This exhibition gathered together inlaid patchworks produced in central Europe in the 18th century and in Britain in the 19th and showed that these textiles were alike in originating from non-domestic workshops run by nuns or by male tailors, and in reflecting specific social or religious concerns through their images. Intarsia patchworks produced in Görlitz, Silesia in the mid-18th century were a response to the political unrest of the Seven Years’ War, and to competition to the town tailors’ guild from unregistered newcomers.9 A hanging made around 1800 for the Royal House of Prussia reproduced images of people, animals and birds copied from books, and seems to have been used as an educational tool for the young Prince Friedrich William IV (born 1795).10 An 18th-century hanging with religious images was displayed for money, with its owner living off the proceeds.11 These uses of intarsia patchwork as a statement of the maker’s skill, as an educational resource, and as a source of continuing income, are important precedents for the 19th century British examples.

Intarsia patchwork at the Great Exhibition

The farmyard panel in the V&A collection was donated with a statement that it had been exhibited at the Great Exhibition in London. This is surprising if we think of the Exhibition as a space for displaying the best of manufactured products: textile machinery, porcelain vases, and carved furniture. Indeed, its main halls were taken up with large set-pieces sponsored by manufacturers, and by the governments of European nations, China, and British colonies. There were, however, many items on display made by individuals, either professionals or amateurs. These had been offered for exhibition through 297 local committees that forwarded works for consideration by the London subcommittees dealing with the thirty different categories of objects to be exhibited.12 Many of the items in Class XIX, ‘Tapestry, Lace and Embroidery’, were submitted by individuals who described themselves as ‘Inventor and Manufacturer’, including thirty soldiers or policemen.13

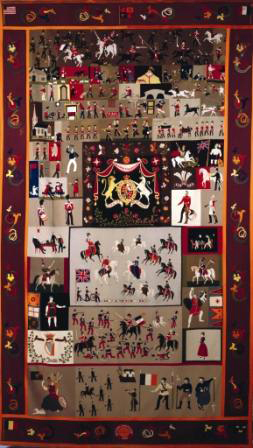

Among the unusual textiles on display were five pieces described as table-covers or counterpanes, made from wool cloth in the technique of ‘mosaic needlework’. The makers’ statements emphasised the size and complexity of the work, and the time taken to complete it. For example number 218, made by J. Johnstone of 102 Graham Street, Airdrie, Scotland, was described as a ’Table-cover, consisting of 2,000 pieces of cloth, arranged into 23 historical and imagined characters…The design and execution is the sole work of the exhibitor, and has occupied his leisure hours for 18 years’.14 Number 382, by John Brayshaw, a tailor from Lancaster, was a ‘counterpane of Mosaic needlework, 12 feet long by 10 feet wide, divided into 44 compartments, each representing a popular print’.15 However the description of number 307, by Steven Stokes, a Dublin policeman, emphasised not the work involved, but the patriotic themes represented: ‘Table-cover of mosaic cloth-work, composed of cloth fine-drawn together, representing the royal arms; the royal family at a review; the capture of the French eagle by the Royal Dragoons at Waterloo; a sketch from Ballingarry; a war chariot, etc’.16 This piece has survived, and was presented to the National Museum of Ireland by Stokes’ descendants in 1960 (fig. 2).

With it came documentation showing that all or part of the textile was shown to Queen Victoria on her visit to Ireland in 1849.17 This event is probably commemorated in the central panel, which shows the Queen and Royal Family mounted and in uniform at a military review. After its display in London in 1851, where it was awarded a bronze medal, Stokes’ panel was shown in the Irish Industrial Exhibition in Dublin in 1853, where it was praised by reviewers.18 It was also exhibited for charity in 1881, and a pamphlet explaining it was printed in 1895, probably to accompany further displays.19

The motivation for Stokes’ work, which apparently took him 24 years to make, is not addressed in the pamphlet or in press accounts.20 As he was a police officer who rose to the level of Inspector, it was probably not financial. There are several references in the patchwork scenes to the destructive effects of excess drinking, so it is possible that the project was begun as a form of escape from the alcoholic ‘canteen culture’ Stokes had experienced when he served in the British army from 1802 to 1836.21 The scenes depicted in this textile are not the peaceful landscapes suggested by the 1851 description of ‘A Scene at Ballingary’ and ‘Donnybrook Fair’, but highly politicised renditions of the efforts of the Irish Police to enforce order in the face of Republican opposition. A scene showing a Republican uprising at Ballingarry is visually opposed to one from the battle of Waterloo, equating Irish rebels with Napoleonic troops. Thus the display of this textile in public would speak not only of the skill, patience and patriotism of its maker, but of the legitimacy of English rule in Ireland.

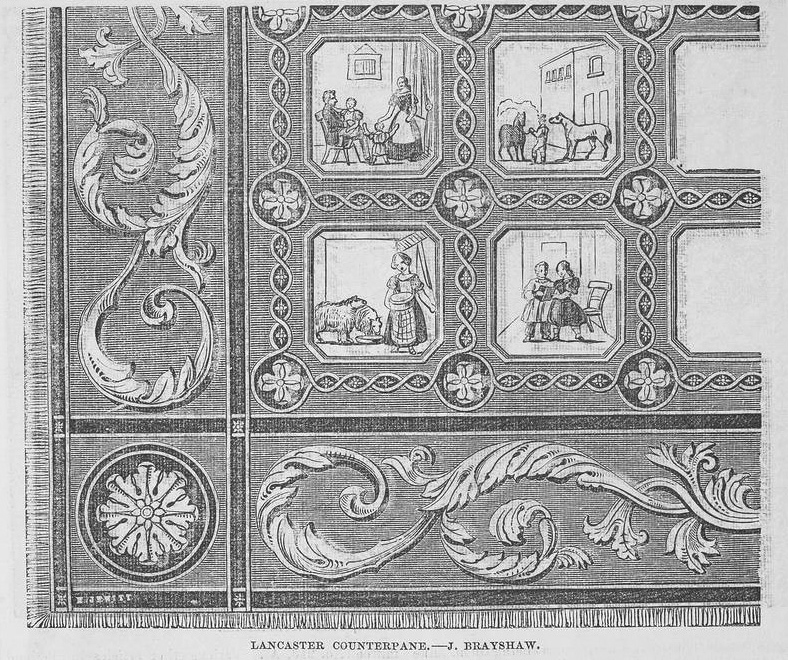

In spite of Stokes’ medal, the only example of intarsia patchwork to receive a favourable notice in the Illustrated Exhibitor, a 550 page catalogue of the exhibition, was the hanging by Brayshaw. A brief description of the piece was supplemented by an engraving of one corner, showing four of the pictorial panels, and the internal and external borders decorated with a ‘handsome scroll’ (fig. 3).22

One of the scenes, showing a man and two horses, is similar in subject and composition to the farmyard panel, and the scrolled internal border is also very similar. The Illustrated Exhibitor was lukewarm in its appreciation of Brayshaw’s textile as ‘a work of immense labour’, while praising an embroidered copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Last Supper’ made by a lady amateur as ‘artistic’ and evidence of ‘great skill and taste’. The article went on to disparage the taste of working-class exhibitors as a group:

‘Many of the exhibitors, indeed, appear to have been under the delusion of believing that the size of a piece of work and the number of years that had been wasted over it, were the causes that would principally entitle it to a place in the Exhibition; and this notion has doubtless caused this display on the walls of our great Palace of some of the trash which is there to be found’.23

Brayshaw’s textile may have escaped the general condemnation by using high art as a source of inspiration. The reviews of his work in local newspapers state that the pictorial panels were taken from prints by the 18th-century artist George Morland, and the layout of the whole, with elaborate scrolling frames around each scene, replicated late 18th-century arrangements of prints in interior decoration and in furnishing textiles.24

Financial motivations for intarsia patchwork

Stokes’ patchwork is the only one exhibited at the Crystal Palace known to have survived in one piece. In October 1851, near the end of the Exhibition, there was a leak in the glass roof, ‘to the great discomfort of some of the exhibitors’.25 As the patchwork panels were displayed hanging from the roof to allow them to be seen in full, they would have been liable to damage from leaks.26 This may account for the disappearance of the other examples, which are not mentioned in newspapers after 1851, and are not preserved in museum collections.

The damage to goods displayed in the Great Exhibition would have been a severe blow to exhibitors who had invested time and effort in producing items that they hoped would earn them money. John Brayshaw’s patchwork hanging had been completed by November 1850, when 1000 people paid to see it in Penrith, Cumbria.27 Brayshaw had taken the textile on a tour of North-West England, publicising it with advertisements and editorials in the local newspapers:

‘J Brayshaw begs to announce that having perfected the ORNAMENTAL COUNTERPANE intended for the May EXHIBITION OF INDUSTRY, he intends to exhibit it to the public of Preston, commencing on Thursday, February 6th, 1851, Wednesdays excepted. During the Exhibition a band will be in attendance. The Exhibition will open at 10 o’clock in the morning, and close at 9 in the evening. Price of admission sixpence. Visitors are requested not to touch the Needlework. To understand the different representations parties visiting can refer to the Bill’.28

This notice makes it clear that Brayshaw’s exhibition was a commercial venture: 1,000 visitors paying 6d a head would give gross takings of £25, a considerable sum when a skilled working man might earn less than £1 per week. Brayshaw’s practice was modelled on the ‘mechanics’ exhibitions’ held in industrial areas from 1837 onwards, in its claims to present both a technical innovation and a work of art, and in charging a 6d entrance fee.29 The printed guide or ‘Bill’ would add to the educational value of the event. This patchwork was exhibited around Lancashire throughout February and March 1851 before being delivered to London, where it had been accepted for the Great Exhibition.30 As the opening day approached, the Preston Guardian carried several reminders that Brayshaw’s textile would be on display, and that visitors should not miss this work of local interest.31

The strongest evidence of all for the financial value of inlaid patchwork comes from the case of Michael Zumpf, a Hungarian tailor living in London. In 1875 Zumpf was involved in a court case to reclaim three inlaid patchwork table covers from a trickster who offered to sell them to the Duchess of Edinburgh, but instead sold them to a pawn shop and kept the proceeds.32 These textiles were valued by Zumpf at £300, an enormous sum. According to court reports Zumpf and a friend had made eight inlaid textiles, one of them a copy of the ‘picture of Lord Palmerston and the members of his Ministry in the House of Commons’. In 1888 these pieces were included in an exhibition of ‘high-class tailoring from London and the provinces’ organised by the London Practical Foremen Tailors’ Association: ‘On a dark blue ground Zumpf has reproduced, with the help of thousands of pieces of cloth, some of the minutest description, a well-known picture of the Privy Council’.33

Artisans’ patchworks in other exhibitions

There were many other exhibitions both before and after 1851 that aimed to show the public the best examples of British technical and aesthetic innovation.34 As at the Great Exhibition, exhibitors ranged from large-scale manufacturers to individual working men and women. The Crystal Palace itself was moved to Sydenham, where it became a venue for ‘rational recreation’ such as Temperance festivals, choral concerts, and exhibitions that aimed to attract a broad cross-section of British society.35 Detailed catalogues of these exhibitions do not survive, but publications from regional events such as the 1865 Working Men’s Industrial Exhibition, Birmingham suggest that the taste for exhibiting elaborate patchworks continued. The Birmingham exhibition included a ‘Table Cloth and Bed Cover, the latter containing 17,000 squares of cloth, was made from old regimental suits’, submitted by a former soldier, and a ‘Patchwork, Bed Quilt, and Cover, production of leisure hours’ by a wire welder.36 Although the descriptions do not say whether either of these pieces included pictorial panels, the references to the number of pieces included, and their production in leisure time over a number of years, are similar to the catalogue descriptions of intarsia patchworks at the Great Exhibition.

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s there were exhibitions of intarsia patchworks staged by individuals, similar to those organised by Brayshaw in 1851. John Monro, a tailor from Paisley, listed his occupation in the 1851 census as ‘Assistant Exhibiter of the Royal Table Cover’, implying that he saw this as a money-making venture.37 This textile is now in the collection of Glasgow Museums, and is composed of seven panels with ships, figures, and landscapes surrounded by geometric borders, all worked in intarsia patchwork (fig. 4).

These are surrounded by an outer border of plain fabric, which is embroidered with hundreds of names of writers, scientists, theologians, and jurists, and a statement of the maker’s personal philosophy. Monro’s motivation for spending 18 years of leisure time on this textile is further clarified by newspaper reports of a lecture he gave to the Belfast Revival Temperance Association in November 1860, when he used his patchwork as an example of ‘what patience and perseverance could accomplish, and urged upon the young men present to practice these virtues; and, in order to do so, they should become total abstainers’.38 Menzies Moffat of Biggar made two elaborate intarsia patchwork hangings in the 1860s, the Royal Crimean Hero Table Cover and the Star Tablecover.39 These were exhibited by him for money, as a surviving publicity poster demonstrates. But the Star Tablecover was also carried as a banner in a procession backing the 1884 Reform Act with ‘The Franchise Bill is the Tailor’s Will’ stitched on the back in beads.40 An anonymous intarsia patchwork in the V&A collections has references to both Temperance and contemporary politics, with representations of Father Matthew the Temperance preacher and of Wat Tyler, leader of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1380, and an allegory of the Anti-Corn Law League (which ostensibly campaigned to bring down the price of bread) (fig. 5).41

The repeated references to Temperance in these patchworks reflects the cultural importance of this movement in Victorian Britain, with a nationwide network of groups that offered lectures, meetings, social activities, and services such as life insurance.42 These were intended to provide a substitute for working men’s friendly societies and trade groups based in public houses, which often led to abuses such as compulsory ‘treating’.43 Finding non-alcoholic leisure activities would have been a particular problem for soldiers and policemen living in barracks far from home and not permitted to marry. There is some evidence that patchwork was promoted as a form of therapy for soldiers trying to avoid alcoholism. The British Workman, a Temperance magazine aimed at educated working people, published several articles in the mid-1870s on this topic. In 1873 it featured Private Roberts, who, when he gave up alcohol, reckoned that ‘I must be employed, or I shall get into mischief’ and made three patchwork quilts, one with 28,000 pieces, which he sold to his commanding officer for £10.44 The accompanying image shows a geometric patchwork similar to one in the V&A associated with Private Francis Brayley.45 Sue Prichard’s research suggests that servicemen were encouraged to produce craft items for display in Soldiers’ Industrial Exhibitions as a distraction from drinking; this may account for the numerous surviving geometric patchworks with military associations.46

The rational use of working men’s free time was also a political issue. The period when the intarsia patchworks were being made, from the 1830s through to the 1860s, was one when the working-class majority of the British population was largely barred from political representation. Alongside political initiatives, rallies, and petitions to Parliament to extend the vote there was a widespread movement to educate the working classes as future voters.47 This was carried out through Mechanics’ Institutes, lectures and study groups, and through mass market periodicals such as the Penny Magazine.48 In this context, viewing a textile representing military heroes, celebrities, and exotic animals might be seen as an educational, or at least rational, way of spending leisure time, especially when the textile was itself a testimony to the maker’s sobriety and hard work.

Intarsia patchwork seems to have been a purely masculine craft in 19th-century Britain. Women were represented at exhibitions from 1851 onwards, both as professional needlewomen and as lady amateurs, and some of their products sound as elaborate and as time-consuming as intarsia patchwork: ‘no. 217, Maria Johnson, Hull - Patchwork quilt in 13,500 pieces of silk, satin, and velvet, with white embroidered flowers’.49 However more typical women’s exhibits were made from materials such as cotton crochet, and described as imitations, rather than as independent creations: ‘140: Crick, Ellen – A Veil worked by the needle, in imitation of Honiton lace, and in the hope that it may be the means of giving employment to many poor needle-women’.50 The numerous pictorial embroideries exhibited by women were described through their scriptural subjects, or as copies of a painted original, as if the work needed to be given validity by association with art or religion: ‘No. 349: Lady Griffin Williams, ‘The Last Supper, from the painting by Leonardo da Vinci’.51 Some women exhibitors were clearly professionals hoping to showcase their talents through group exhibitions. After the closure in 1845 of Mary Linwood’s Leicester Square gallery devoted to her needlework renditions of oil paintings there seem to have been few opportunities for women to present themselves as textile artists.52 Even when women’s work included images with political relevance, like the slave and the distressed sailor on Ann West’s appliqué coverlet, it does not seem to have been used to argue for a political end. This reflects the exclusion of most women from the political process, notwithstanding their involvement in causes such as the abolition of slavery. Female exhibitors’ silence over the time taken to produce their work – in contrast to the emphatic statements of Monro and other men – also reflect contemporary valuations of female labour. The commonest female employments, domestic service and dressmaking, were seen as extensions of women’s innate skills in home-making, rather than as professions regulated by trade bodies and by employment law.53

As the clothing industry moved towards mass-production from the 1840s onwards, low-paid female seamstresses were used to undercut the wages of male tailors.54 So the hand-stitched intarsia patchwork of Brayshaw, Monro or Zumpf would help to promote ‘high-class [male] tailoring skills’ in the face of mass-produced [female] competition. The images rendered in the patchworks would demonstrate the maker’s knowledge of history, art, religion, the natural world, and patriotic themes. The persistence and sobriety required for a lengthy patchwork project would be evidence of the maker’s ability to withstand the temptations of the drinking culture that pervaded workshops and barracks. All of these claims, and their implications for the anonymous maker’s status as a rational citizen worthy of the vote, can be read in the seemingly innocuous farmyard panel. As a review of the 1888 exhibition of Zumpf’s intarsia patchworks stated: ‘They are worthy of a place in one of our National Museums, and will compare favourably with many much vaunted tapestries’.55

Endnotes

-

AP.27-1917; published in Morris, Barbara. Victorian Embroidery. London: B.T. Batsford, 1969: 64 and plate 31; Ehrman, Edwina. ‘Picture of a Farmyard Scene’ in Inlaid Patchwork in Europe from 1500 to the Present/Tuchintarsien in Europa von 1500 bis heute, edited by Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow, Salwa Joram, Erika Karasek. Regensburg/Berlin: Schnell & Steiner GmbH/Museum Europäischer Kulturen, 2009: 279-81. ↩︎

-

Bruseberg, Gisela. ‘The Technique of Textile Pictorial Inlay’ in Inlaid Patchwork in Europe. 31-5. For the origins of the technique, see Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow and Salwa Joram, ‘Cloth intarsia in Europe, an Overview’ in Inlaid Patchwork in Europe: 21-30; Jennifer Wearden and Patricia L. Baker. Iranian Textiles. London: V&A Publications, 2010: 62-5 and 150-8. ↩︎

-

Intarsia patchwork is also made in non-woven felt by many central Asian traditional cultures. The earliest known examples are from the Scythian culture, preserved in the 7th – 2nd Century BC frozen tombs of Pazyryk, Siberia, See Burkett, Mary. The Art of the Felt Maker. Kendal: Abbot Hall Art Gallery, 1979. ↩︎

-

Colby, Averil. Patchwork. London: B. T. Batsford, 1958: 127-8 and figs 152; 156; Morris. Victorian Embroidery. 64-5 and figs 28; 31. ↩︎

-

Swain, Margaret. Figures on Fabric. London: A&C Black, 1980; Rae, Janet. Quilts of the British Isles. London: Constable, 1987: 94-8; Janet Rae and Margaret Tucker, ‘Quilts with Special Associations’ in Quilt Treasures: the Quilters’ Guild Heritage Search. London: Deirdre McDonald Books, 1995: fig.148 on p.178. ↩︎

-

Rose, Clare. ‘Stitched Inlay: a Geographical Puzzle’ in Hali. 106 (September 1999): 78-82; Rose, Clare. Nineteenth-century Tailors’ Quilts and the Visual culture of Chartism. (Paper presented at Wild by Design, International Quilt Study Center, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, 27 February – 1 March 2003); Clare, Rose. Popular or Radical? Reading 19th century tailors’ quilts. (Paper presented at Radical History, Ruskin College, Oxford, 17 March 2007). ↩︎

-

Parry, Linda. ‘Complexity and context: nineteenth-century British quilts’ in Quilts 1700-2010, Hidden Histories, Untold Stories, edited by Sue Prichard. London: V&A Publications, 2010: 58- 83; Breward, Christopher. ‘Sewing soldiers’ in Quilts 1700-2010. London: V&A Publications, 2010: 84-7; Lister, Jenny. ‘Remember Me’: Ann West’s coverlet’ in Quilts 1700-2010. London: V&A Publications, 2010: 88-91; Riding, Jacqueline. ‘His Constant Penelope: epic tales and domestic narratives’ in Quilts 1700-2010. London: V&A Publications, 2010: 156-61. ↩︎

-

Prichard, Sue. ‘Creativity and confinement’ in Quilts 1700-2010. London: V&A Publications, 2010: 92-5. ↩︎

-

Anders, Ines. ‘1755 Inlaid Patchwork from Görlitz Cultural History Museum’ in Inlaid Patchwork in Europe from 1500 to the Present/Tuchintarsien in Europa von 1500 bis heute, edited by Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow, Salwa Joram, Erika Karasek. Regensburg/Berlin: Schnell & Steiner GmbH/Museum Europäischer Kulturen, 2009: 67-75. ↩︎

-

Regine Falkenberg, ‘Textile Edification, Inlaid patchworks from the Royal House of Prussia’, in Inlaid Patchwork in Europe from 1500 to the Present/Tuchintarsien in Europa von 1500 bis heute, edited by Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow, Salwa Joram, Erika Karasek. Regensburg/Berlin: Schnell & Steiner GmbH/Museum Europäischer Kulturen, 2009. ↩︎

-

‘Wolfshagen Cloth hanging, Wolfshagen-Hetzdorf parish church, Germany, catalogue D29’ in Inlaid Patchwork in Europe from 1500 to the Present/Tuchintarsien in Europa von 1500 bis heute, edited by Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow, Salwa Joram, Erika Karasek. Regensburg/Berlin: Schnell & Steiner GmbH/Museum Europäischer Kulturen, 2009: 240-4. ↩︎

-

Auerbach, Jeffrey. The Great Exhibition of 1851: A Nation on Display. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999: 65-80. ↩︎

-

Breward. ‘Sewing soldiers’ in Quilts 1700-2010. London: V&A Publications, 2010: 86. ↩︎

-

Ellis, Richard (ed.). Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations, 1851. Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue. London: W. Clowes and Sons, 1851: 568. Two thousand is a rather small number of pieces for this type of textile; no.135, by William Cook of Chippenham, apparently contained 30,000 pieces of cloth; ibid., 564. ↩︎

-

Ellis. Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations, 1851. Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue. London: W. Clowes and Sons, 1851: 570. ↩︎

-

Ellis. Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations, 1851. Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue. London: W. Clowes and Sons, 1851: 569. ↩︎

-

Lar Joye and Alex Ward. ‘The “Stokes Tapestry” or Royal Table Cover of Inlaid Patchwork’ in Inlaid Patchwork in Europe from 1500 to the Present/Tuchintarsien in Europa von 1500 bis heute, edited by Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow, Salwa Joram, Erika Karasek. Regensburg/Berlin: Schnell & Steiner GmbH/Museum Europäischer Kulturen, 2009: 107-117. ↩︎

-

‘The Great Industrial Exhibition’. Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser. Dublin, Ireland, 19 May 1853: 3. ↩︎

-

‘Dalkey Church Bazaar’. Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser. Dublin, Ireland, 11 August 1881: 7; Lar Joye and Alex Ward. ‘"The “Stokes Tapestry” or Royal Table Cover of Inlaid Patchwork’ in Inlaid Patchwork in Europe from 1500 to the Present/Tuchintarsien in Europa von 1500 bis heute, edited by Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow, Salwa Joram, Erika Karasek. Regensburg/Berlin: Schnell & Steiner GmbH/Museum Europäischer Kulturen, 2009: 109. ↩︎

-

‘Dalkey Church Bazaar’. Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser. Dublin, Ireland, 11 August 1881. ↩︎

-

Prichard, Sue. Introduction to Quilts 1700-2010. London: V&A Publications, 2010: 18; Joye and Ward, ‘The Stokes Tapestry’ in Inlaid Patchwork in Europe from 1500 to the Present/Tuchintarsien in Europa von 1500 bis heute, edited by Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow, Salwa Joram, Erika Karasek. Regensburg/Berlin: Schnell & Steiner GmbH/Museum Europäischer Kulturen, 2009: 108. ↩︎

-

‘Needlework in the Crystal Palace’. Illustrated Exhibitor. No.21, 25 October 1851: 391. ↩︎

-

‘Needlework in the Crystal Palace’. Illustrated Exhibitor. No.16, 20 September 1851: 294-5. Another article on the same theme was ‘Caprices of Invention’. Illustrated London News. 23 August 1851: 254. ↩︎

-

For example in the ‘Print Room’ at Uppark, Sussex, and the printed cotton Les Monuments de Paris, Louis-Hippolyte Lebas, 1816. Museum no. 1622-1899. ↩︎

-

‘The Great Exhibition’. Daily News. 2 October 1851: 5; ‘The Great Exhibition’. Daily News. 4 October 1851: 5. ↩︎

-

Large textiles suspended from the roof beams above the galleries can be seen in the frontispiece to Strutt, J.G (ed.). Tallis’s History and Description of the Crystal Palace and the Exhibition of the World’s Industry in 1851. London and New York: The London Printing and Publishing Company, 1851: vol.III. ↩︎

-

‘A Pictorial Quilt’. Morning Chronicle. 2 November 1850: 4. ↩︎

-

‘Advertisement’. Preston Guardian. 1 February 1851: 1. ↩︎

-

Kusamitsu, Toshio. ‘Great Exhibitions before 1851’ in History Workshop Journal. 9 (1980): 70-89. ↩︎

-

‘Specimen of Needlework for the Great Exhibition’. Preston Guardian. 22 February 1851: 8; ‘The Great Exhibition—Local Contributions’. Manchester Times. 19 April 1851: 6. ↩︎

-

‘Brayshaw’s Counterpane’. Preston Guardian. 21 June 1851: 4 ↩︎

-

‘Trials at the Middlesex Sessions: Cruel Fraud’. Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper. 24 October 1875: 4. ↩︎

-

‘Local News: Exhibition of High-Class Tailoring’. Liverpool Mercury. 22 August 1888: 6. This may be the same piece as the intarsia patchwork now in the collection of Annette Gero: see Gero, Annette. ‘An English Inlaid Patchwork with European Influences’ in Inlaid Patchwork in Europe from 1500 to the Present/Tuchintarsien in Europa von 1500 bis heute, edited by Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow, Salwa Joram, Erika Karasek. Regensburg/Berlin: Schnell & Steiner GmbH/Museum Europäischer Kulturen, 2009: 99-105 and 157-9 ↩︎

-

See Kusamitsu. ‘Great Exhibitions before 1851’; Gurney, Peter. ‘An Appropriated Space: the Great Exhibition, the Crystal Palace, and the working class’ in The Great Exhibition of 1851, New Interdisciplinary Essays edited by Louise Purbrick. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001: 114-145. ↩︎

-

Gurney, Peter. ‘An Appropriated Space: the Great Exhibition, the Crystal Palace, and the working class’ in The Great Exhibition of 1851, New Interdisciplinary Essays edited by Louise Purbrick. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001: 122-31. ↩︎

-

Anon. Official Catalogue of the Working Men’s Industrial Exhibition, Birmingham. Birmingham, 1865, no.253: 23 and no.481: 36. ↩︎

-

Quinton, Rebecca. ‘The Royal Clothograph Table Cover’ in Inlaid Patchwork in Europe from 1500 to the Present/Tuchintarsien in Europa von 1500 bis heute, edited by Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow, Salwa Joram, Erika Karasek. Regensburg/Berlin: Schnell & Steiner GmbH/Museum Europäischer Kulturen, 2009: 267-70. ↩︎

-

‘Belfast Revival Temperance Association – Soiree and Presentation’. Belfast News-letter. 15 November 1860: 2. The framing of Temperance in a political rhetoric of working-class uplift was typical of the early 19th century; see Harrison, Brian. ‘Teetotal Chartism’ in The People’s Charter, Democratic Agitation in Early Victorian Britain edited by Stephen Roberts. London: Merlin Press, 2003: 35-63. ↩︎

-

Rose, Clare. ‘Royal Crimean Hero Table Cover’ and ‘Star Table Cover’ in Inlaid Patchwork in Europe from 1500 to the Present/Tuchintarsien in Europa von 1500 bis heute, edited by Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow, Salwa Joram, Erika Karasek. Regensburg/Berlin: Schnell & Steiner GmbH/Museum Europäischer Kulturen, 2009: 249-51 and 252-3. ↩︎

-

Clipping from un-named newspaper dated 11 October 1884, Biggar Museums files. See Rose, Clare. ‘Exhibiting Knowledge: British Inlaid Patchwork’ in Inlaid Patchwork in Europe from 1500 to the Present/Tuchintarsien in Europa von 1500 bis heute, edited by Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow, Salwa Joram, Erika Karasek. Regensburg/Berlin: Schnell & Steiner GmbH/Museum Europäischer Kulturen, 2009: 88-98. ↩︎

-

Quilts 1700-2010. London: V&A Publications, 2010, No.46: 205. Museum no. Circ.114-1962. For the politics of this piece see Rose, ‘Exhibiting Knowledge’, 91. ↩︎

-

Shiman, Lilian. The Crusade against Drink in Victorian England. New York: St Martin’s Press, 1988. ↩︎

-

Harrison, Brian. Drink and the Victorians. Keele: Keele University Press, 1994: 50-6. ↩︎

-

‘Another Patchwork Quilt’. The British Workman. March 1873, 152. This was followed by a fictional treatment of the same topic, “’Right About Face", A Story of a Patchwork Quilt’. The British Workman. February 1874: 198-9. ↩︎

-

Quilts 1700-2010. London: V&A Publications, 2010, No.47: 206. Museum no. T.58-2007; see also Breward, ‘Sewing Soldiers’, plate 1: 84. This patchwork, and others like it, were made using conventional seaming techniques, not intarsia. ↩︎

-

Prichard, Sue. Made by Men, Used by Soldiers. (Paper presented at The Global Quilt: Cultural Contexts, International Quilt Study Center, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2-4 April 2009); see also Rae and Tucker. Quilts with Special Associations. 170–178. ↩︎

-

For the cultural and educational aspects of radicalism, see Yeo, Eileen. ‘Culture and Constraint in Working-Class Movements’ in Popular Culture and Class Conflict 1590-1914, Explorations in the History of Labour and Leisure, edited by Eileen Yeo and Stephen Yeo. Brighton: Harvester, 1981: 155-86. ↩︎

-

See Anderson, Patricia. The Printed Image and the Transformation of Popular Culture 1790-1860. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991: Chapter 2, 50-83. Illustrations in the Penny Magazine are likely to have been the source for the animals and birds depicted on some intarsia patchworks; see Rose, ‘Exhibiting Knowledge’, figs 5 and 6 on 92-3. ↩︎

-

Ellis. Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations, 1851. Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue. London: W. Clowes and Sons, 1851, no. 217: 568. ↩︎

-

Ellis. Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations, 1851. Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue. London: W. Clowes and Sons, 1851: 567. ↩︎

-

Ellis. Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations, 1851. Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue. London: W. Clowes and Sons, 1851: 569. ↩︎

-

Myrone, Martin. ‘Linwood, Mary (1755–1845)’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2004. Online edition, Jan 2008. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/16748 [accessed 7 Jan 2011] ↩︎

-

See Harris, Beth (ed.). Famine and Fashion: Needlewomen in the nineteenth century. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005. ↩︎

-

Blackburn, Sheila. A Fair Day’s Wage for a Fair Day’s Work? Sweated labour and the origins of minimum wage legislation in Britain. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007. ↩︎

-

‘The City of London Practical Master and Foreman Tailors’ Mutual Benefit Society’. The Tailor and Cutter. 12 July 1888: 329. ↩︎