Abstract

This article explores London fashion designers’ use of historic garments for research and inspiration for their collections. Examples of work by graduates from the Royal College of Art, two established designers and an interview with Professor Wendy Dagworthy, Head of Fashion at the RCA, demonstrate how historical research helps to build fashion collections redolent of meaning and narrative.

Research is absolutely central to the fashion design process. It underpins designers’ ideas, informs the shapes and proportions they use, influences the materials they choose to work with and determines the techniques they employ to put them together. Surviving historic garments and images which record what people have worn in the past provide an invaluable research resource for many fashion designers. This paper will explore the diverse ways in which London fashion designers today use these tools to inspire their designs. Examples from the V&A exhibition Future Fashion Now: New design from the Royal College of Art (May 2009 - Feb 2010) will reveal how some recent fashion graduates have applied their personal approaches to research in developing their graduate collections. An interview with Professor Wendy Dagworthy, Head of Fashion at London’s Royal College of Art, will demonstrate the central place research occupies in design education at the college. Interviews with designers at two London-based firms - Stuart Stockdale, Design Director at Jaeger and Barry Tulip, Senior Designer at Dunhill, will illustrate the importance of detailed research in inspiring their design ideas, reinforcing company heritage and developing a narrative behind their work. Finally, I will argue that this research, which enables dialogues between historic and contemporary fashion, helps to build new, more complex narratives about both past and present.

The exhibition Future Fashion Now: New design from the Royal College of Art explored key aspects of the fashion design process. It featured garments and accessories from the degree collections of graduates from the Royal College of Art’s 2008 fashion MA programme. Completed examples from the designers’ graduate collections were displayed alongside their sketchbooks, images of source material, paper patterns, three-dimensional models and equipment they used to make the garments. Each garment or ensemble in the display illustrated an element of the design and making process, offering a glimpse of how the designer approached their research, developed their ideas, experimented with materials and technology, collaborated with students in other disciplines or added subtle details to refine their work. Sections about concept, form, technique and detail illustrated how deeply intertwined these stages of the design process are.

London’s Royal College of Art started its fashion programme in 1948, under the direction of Madge Garland, former fashion editor at Vogue magazine.1 Today, the college welcomes aspiring designers with undergraduate degrees and prepares them for fashion careers through technical workshops, specialist lectures, project critiques and work experience. After a two year Masters Course the RCA’s fashion graduates have gone to fashion houses such as Dior, Burberry, Vivienne Westwood and Chloe, while others, such as Ossie Clark, Boudicca, Julien Macdonald and, more recently Erdem Moralioglu and Carolyn Massey have developed their own labels.2

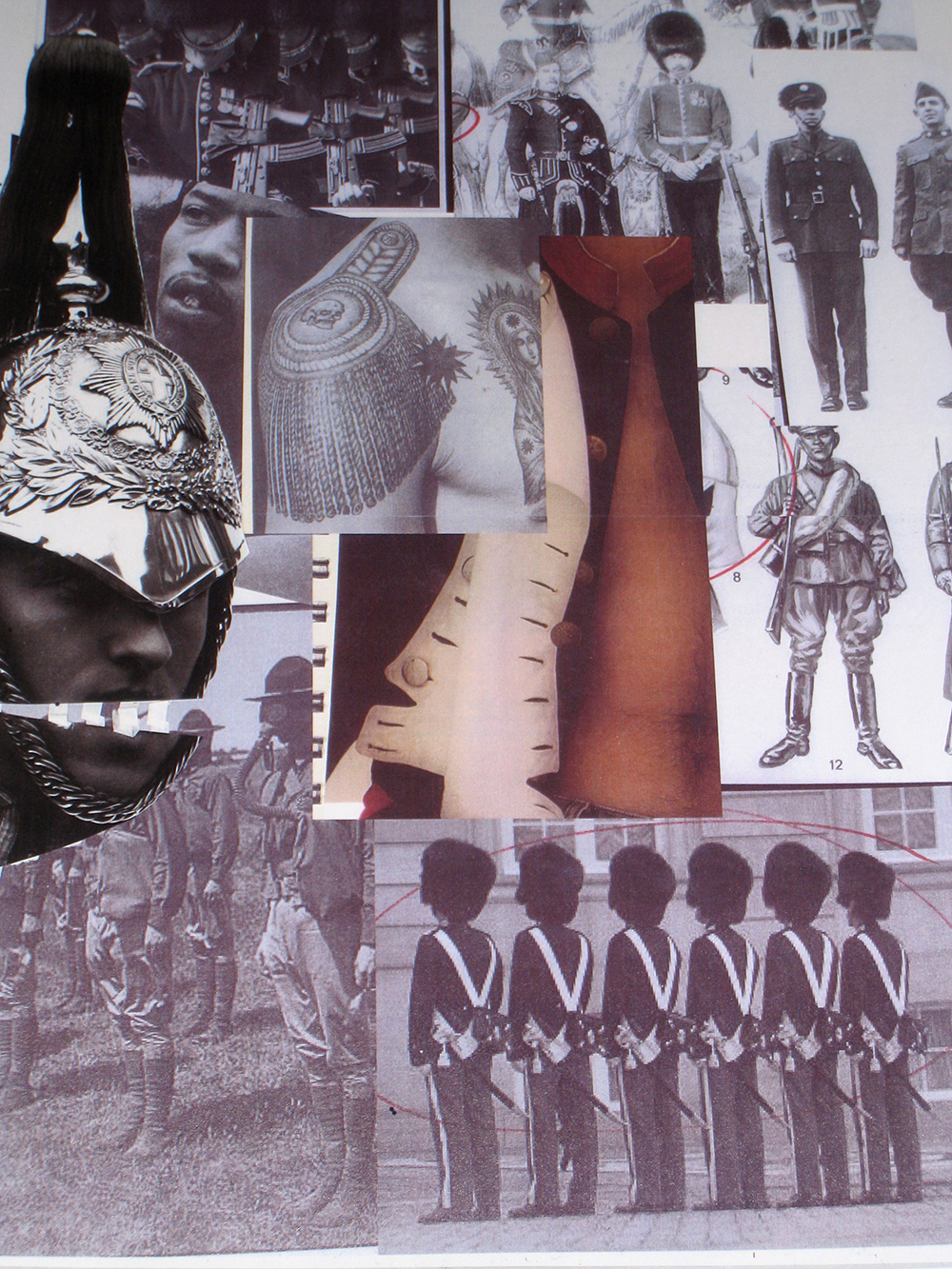

Several of the Royal College of Art graduates whose work was featured in Future Fashion Now took some inspiration from historic garments. For her crystal-clad menswear collection, Katie Eary looked to a wide range of influences, including the uniforms of the Grenadier Guards, 19th-century English tailoring, and Russian literature. Her sketchbook is replete with images of men’s military uniform and swatches of leopard print fabric and leather (fig.1).

For her graduate collection, Eary played with the showy, flamboyant elements of men’s uniform such as metal and braid decoration to create a stage-worthy tailored coat covered in gold crystals with exaggerated, wide hips supported by leather pannier-style structures.

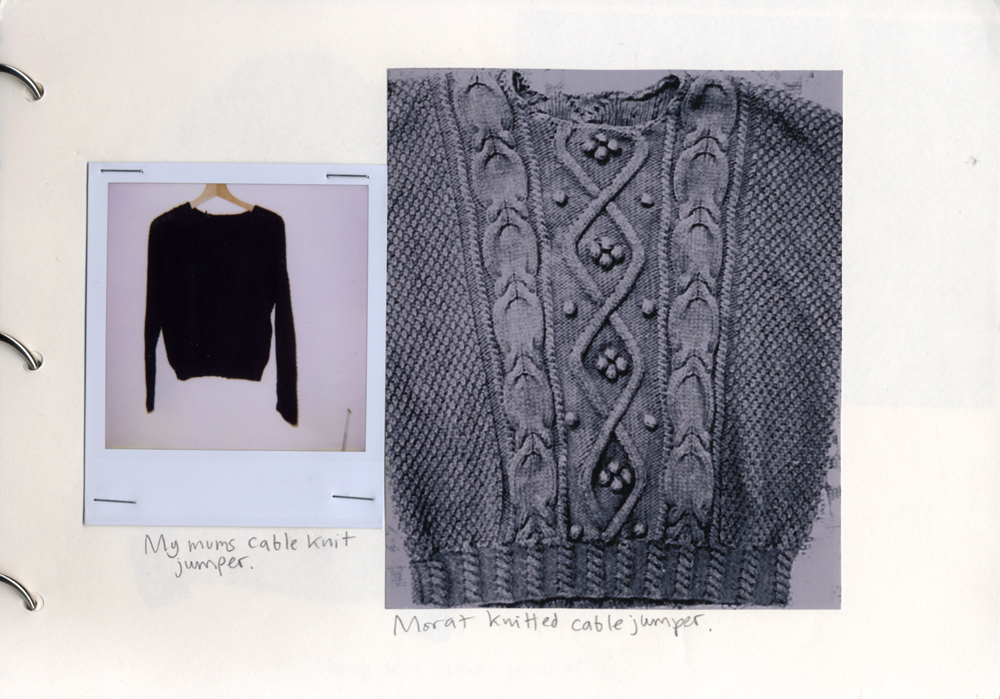

Menswear knitwear designer Siri Johansen’s collection included voluminous, oversize jumpers and trousers based in part on existing classic or favourite garments. For her research, the designer selected basic items such as a cable knit jumper, a herringbone tweed coat and a denim jacket. She focussed on the familiar details of the garments’ patterns and textures, playfully altering their scale and magnifying surface details. Johansen used a range of printing and knitting techniques to expand and exaggerate patterns which are traditionally woven – a herringbone weave wool fabric became extra-large knitted chevrons; twill-woven jeans morphed into knitted trousers with an electronically-produced, enlarged version of denim’s familiar diagonal lines. Future Fashion Now included Johansen’s oversize grey jumper, inspired by a cable knit jumper in her mother’s wardrobe (fig.2). She used an electronic Morat knitting machine to reproduce the cable of the source garment as an extra-large image, in two dimensions instead of three.

Given the Royal College Art’s geographic proximity to the V&A and the close relationship between the two institutions, it is perhaps unsurprising that some of the objects featured in Future Fashion Now were inspired by V&A collections and exhibitions. During a visit to the Modernism (April - July 2006) exhibition at the V&A, womenswear knitwear designer Léa Carreño sketched textile designs by the French artist Sonia Delaunay, which formed part of the displays. Delaunay’s vivid colours and geometric shapes formed part of Carreño’ s extensive body of research, which included images of the costumes of the Ballets Suédois from the early 1920s. Inspired by this research, she produced a graduate collection of dresses knitted in bright stripes and bold blocks of colour (fig.3). This research also led her to experiment with light and heavy weight yarns, which she combined in ways that would move with the body like the more rigid 1920s ballet costumes.

Liam Jackson’s menswear collection was also based around research on historic clothing. He combined wools, velvets, plastics and reflective materials to create tailored jackets, breeches and shirts, drawing parallels between the structured coats and knee-length breeches worn by men in the early 19th century and the weatherproof jackets and short trousers which bicycle couriers wear today. He contrasted light with dark, playing on ideas of bright lights in night time cityscapes, and echoing the images of road workers wearing reflective uniforms which he had collected in his research. For details of cut, Jackson looked to books on men’s dress history but he also examined original garments in vintage clothing stores and theatrical costumiers.

Research is absolutely central to fashion education at the Royal College of Art. Under the direction of Professor Wendy Dagworthy, fashion MA students are encouraged to develop original ideas through detailed primary research. Beyond their lectures, tutorials, work critiques and dissertations, students are required to take part in a variety of research-oriented projects. Some of these projects involve studying original objects in museums. One recent group of students visited the Prints and Drawings Study Room at the V&A. Each student had to choose two images from a large selection of material then develop their ideas through research and build a collection around their chosen visual references. ‘We wanted them to do primary research and look at real things’, says Wendy Dagworthy.3

Where appropriate, RCA fashion students are encouraged to study examples of historic clothing. ‘They’re a source that you shouldn’t miss’, Dagworthy argues, ‘they can inform you about silhouette, details, prints, fabrics…they’re a really fantastic source of research’. She urges her students to visit museums to view historic fashion as well as art, architecture, furniture, sculpture. Of course not all fashion students at the RCA look to museums for inspiration. Among the 2008 graduates, some referenced their immediate surroundings, while others researched music or philosophy. ‘When we’re doing tutorials, we give them ideas about where they can do research related to their work’, she explains, ‘ideas can come from anywhere – you just need feeding and that’s what museums can do’. For many designers, looking to the past has produced groundbreaking work. But Dagworthy adds a note of caution: ‘you have to be careful - I think it’s fine to look to the past but you have to do it in a different, contemporary way’.

This creative appropriation of elements of historic styles is a long-established theme among London-based fashion designers. From the beginning of her career in the late 19th century, the couturière Lady Duff Gordon, known as Lucile, frequently looked to historic garments for inspiration. Writing in the 1920s, she hinted at the romantic quality these historical references lent to her designs. She remembered: ‘I loosed upon a startled London, a London of flannel underclothes, woollen stockings and voluminous petticoats, a cascade of chiffons, of draperies as lovely as those of Ancient Greece’.4 Lucile explained her design and making methods in columns she wrote for The New York American Examiner, citing museum collections among her research sources. The columnar designs she created between 1910 and 1913 had names inspired by the late 18th and early 19th centuries, such as ‘Directoire’, ‘Empire’ and ‘Josephine’.5

The study of historic garments also formed part of Norman Hartnell’s research. Dresses worn by sitters in the mid 19th century paintings of Franz Xavier Winterhalter inspired the full-skirted, crinoline styles he produced for society ladies in the 1930s. In advance of designing dresses for the Maids of Honour to wear during the coronation of George VI in 1937, Queen Mary urged the couturier to examine surviving coronation clothing at an exhibition assembled by the Royal School of Needlework.6 The enormous commission he received for the 1953 coronation prompted more detailed historical research at the London Museum and the London Library. His resulting designs included modern coronation robes and caps of state which blended sympathetically with the historic garments at the ceremony and a coronation dress for The Queen embroidered with traditional symbols of the Commonwealth.7

In more recent decades, several British designers have become renowned for producing fashion collections laden with historical references. Vivienne Westwood has consistently borrowed and remixed elements of historic dress in her designs. At the beginning of her career, Westwood used vintage clothing as source material for her work, unpicking 1950s garments to understand how they were constructed.8 In subsequent years, the designer built on this interest in historic styles of dress producing, for example, short, 19th-century inspired crinolines for her Mini-Crini collection in spring/summer 1985. Her Portrait collection (autumn/winter 1990-1) included shawls and 18th-century style corsets printed with reproductions of Francois Boucher’s painting Shepherd Watching a Sleeping Shepherdess in London’s Wallace Collection, and some of her later work is replete with references to historical tailoring and dress construction. Westwood’s designs are meticulously researched. She has continually examined historic cut, and has studied examples of historic garments in stored collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum.9 As Professor of Fashion at the Vienna Academy of Applied Arts from 1989 to 1991, and later as a fashion educator in Germany, she urged her students to study and copy historic garments in order to further their knowledge of cut and technique. Throughout her career, she has used her thorough understanding of historic garments to create new designs which challenge orthodox ideas of beauty and sexuality.10 Her approach does not aim to replicate the past but, as Rebecca Arnold has argued, it represents a utopian vision, offering an escape to a nobler, more elegant existence.11

London-based Zandra Rhodes has also looked to the past when researching some of her designs. For her autumn/winter 1981 collection, Rhodes designed a bold evening ensemble inspired by examples of 18th-century dress she had studied at the V&A. She donated the dramatic black quilted-satin bodice with gold-pleated polyamide, polyester and lamé skirt and panniers to the museum.12

Alexander McQueen remains well-known for his highly original collections and spectacular fashion shows which frequently evoked historical themes. McQueen took apprenticeships at the Savile Row tailors Anderson & Sheppard and then Gieves & Hawkes where he learned traditional British tailoring techniques. He later worked as a pattern cutter at the theatrical costumiers Angels and Bermans where he further focused his training in historic garment construction.13 McQueen’s 1995 Highland Rape collection, which placed him firmly on the world stage, was inspired by his own family history and the Highland Clearances. His radical re-presentation of historical narratives continued throughout his career alongside his innovative combination of contemporary and historic cut and materials. ‘I like to challenge history’, he stated in the 2008 BBC series British Style Genius, in which he emphasised the semi-autobiographical nature of some of his historical subject choices.14

Whether challenging history, fostering dialogues between past and present, offering an escape from reality or bringing long-standing traditions up-to-date, studies of the past have lent an authority and a deeper meaning to the work of many London designers. Through their innovative and often groundbreaking approaches these designers have devised complex narratives by nurturing unexpected relationships between the historic and the contemporary and between seemingly divergent individuals and styles. This shared, but very individual, focus on the historical and, in particular, the shape, cut, construction, materials and decoration of historic dress has been a key feature in attracting the ‘AngloMania’ which Andrew Bolton explored in the 2006 exhibition of the same name at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. As an extension of the Anglomania which compelled figures such as Voltaire to endorse an England they believed to be characterised by freedom and tolerance, Bolton emphasises Anglomania’s continued existence as a stylistic phenomenon. It is, he argues, ‘based on idealized concepts of English culture that the English themselves recognize, but also, in a form of “autophilia", actively promote and perpetuate’.15 This self-referential tendency to incorporate the British past into new design has been a common thread among well-known London brands and couturiers.

The designer Stuart Stockdale also recognises historic fashion as an invaluable research tool. Stockdale has been Design Director at Jaeger since 2008. To support his work for heritage brands, he has used historical garments, museum collections, vintage finds and company archives to inspire his designs. Stockdale studied fashion design at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in London where, for his degree show, he took inspiration from the Industrial Revolution – one dress he created featured an integral loom, designed to weave the model’s skirt as she wore it. After completing an MA in fashion at the RCA, he worked for two and a half years at Romeo Gigli in Milan, then moved to New York to design for American brand J Crew. A few years later, he returned to London where, after a brief period working for Jasper Conran, he became Design Director for Pringle of Scotland.16

Between 2000 and 2005, Stockdale worked to revive Pringle’s staid image with a flagship store on the corner of London’s New Bond Street, including a glamorous advertising campaign featuring model Sophie Dahl, and runway shows at London Fashion Week. He plundered the company archive, using argyle pattern jumpers and twinsets, the label’s core garments, with a sense of irony. Stockdale never lost sight of the brand’s heritage. The womenswear collection he launched in 2003 featured bra tops and knickers in the company’s signature Argyle pattern, lending it a more up-to-date, sexier image.17 ‘I really got into the whole heritage of the brand’, Stockdale remembers. He made regular visits to the company archive in Scotland and tracked down early Pringle designs in museums. ‘I think something new would catch your eye each season – something you wouldn’t give [a] second glance [to], suddenly it seemed really new’.18

Stockdale worked with historic garments in the Pringle archive to bring them up to date. The retired golfer Nick Faldo was the face of Pringle when Stockdale joined the company in 2000, and golf jumpers were the company’s mainstay. For his autumn/winter 2005 menswear collection runway show in Milan, Stockdale gave the familiar argyle pattern jumper an edgy, teddy boy look, complete with donkey jackets, winkle pickers and big quiffs. The fashion press took notice, he recalls, ‘they remember that first men’s show. I made [argyle sweaters] a little bit more rock and roll’. Later that year, Stockdale returned to the company archive for Pringle’s 190th anniversary, for which he produced a capsule collection of 19 garments – one item for each decade of the company’s history. Each garment was a modernised version of an item in the archive. Stockdale tried to make each new item as true to the original archive garment as possible, tweaking style and fit to suit a modern customer and adapting materials and techniques to today’s standards. Looking back on these designs, Stockdale acknowledges he might do things differently now. ‘I think it was important [to reference the past]. In hindsight I think it did a little bit too much, a bit literally, maybe. Instead of thinking “this is amazing, how is it right for now?" I would think “this is amazing, I want to recreate it.” I think that was kind of a learning curve’.

At the end of 2005, Stockdale became Design Director at Holliday and Brown, a British firm which started making men’s accessories in 1926. Again, Stockdale had access to an extensive archive of fabrics, ‘the wildest weaves and prints’, which he used to inspire his designs. He also used as a reference point the historic menswear in the Royal Ceremonial Dress Collection at Kensington Palace. He studied examples of 19th and early 20th-century men’s court uniform, closely examining details such as braid, epaulettes and embroidery. ‘Holliday and Brown just seemed so regal and British, and court dress was just the perfect thing’, he recalls. Stockdale introduced similar details into his first menswear collection at Holliday and Brown, having them subtly woven into the fabrics he designed. One jacket featured a ceremonial sash, cutting diagonally across the front and an understated hint of epaulette at one shoulder (fig.4). He consulted the Royal Ceremonial Dress Collection again for Holliday and Brown’s autumn/winter 2008 womenswear collection, incorporating braid, and gold cord aiguillettes into his designs.

Historical references remain an important feature of Stockdale’s work at Jaeger, where he has been Design Director since 2008. Each season, the Jaeger by Jaeger collection includes garments which are directly influenced by items in the Jaeger archive (fig.5). For example, the brand’s autumn/winter 2009 advertising campaign featured a shearling and patent leather coat inspired by a coat the firm produced in the 1960s (fig.6).

While Stockdale prefers to keep the collections more current, his strong interest in fashion history remains a key influence. ‘I still vintage shop all the time but in a different kind of way. We have a good archive of vintage pieces, we have a really great vintage collector in New York, and sometimes we hire vintage pieces in Paris’. Stockdale’s research helps to generate a meaningful collection underpinned by dialogues between Jaeger’s past and its present. These dialogues form part of an overarching narrative about the sustained presence of Dr. Jaeger’s original working principles of producing high-quality garments made of natural fibres. This narrative unfolds against a background of a creative tension behind old and new. The designer cherry-picks and sometimes subverts elements of the company’s heritage in order to reinvigorate it. This clever use of material from Jaeger’s own archive works to reinforce the company’s identity as a heritage brand. It emphasises a continuity between Jaeger, as it appeared during the second half of the 19th century, and the considerably more fashion-conscious image it has now.

Menswear designer Barry Tulip has used garments from the Dunhill archive in a similar way to Stockdale at Jaeger, incorporating details of cut and decoration into his new designs in ways which emphasise the brand’s history. Tulip has referenced historic fashion throughout his career. His interest in historic clothing developed early. From the age of five, he would sit at family gatherings, passing the time sketching outfits for people he knew. ‘I was obsessed with Charles I … by the proportions, by the detailing - the pearls dripping off of lace, and all those weird shapes they had [later] in the eighteenth century, like panniers’, he recalls. ‘I think that’s where it all started, this idea of messing around with shape, form and proportion, and having this obsession with luxury and status’.19

After completing a foundation course at Ravensbourne and a work placement at Alexander McQueen, Tulip took a BA in womenswear and marketing at Central Saint Martins, continuing his education there with an MA in womenswear. His degree collections involved some detailed historical research on surviving garments designed by American designer Claire McCardell at the V&A. After graduation, he moved to Milan to work as Wovens Designer for Z Zegna at the Italian men’s luxury clothing brand Ermenegildo Zegna. Under the leadership of the company’s creative director, Tulip was given ample time to research and develop new ideas. He travelled, bought vintage clothing and hired garments from private archives such as Carlo Manzi in London. In Italy, he made regular visits to Angelo, and their archive collection of Pucci, Capucci gowns and 1970s eveningwear and acquired vintage garments at Belgioioso market near Pavia (a key source for many of the world’s top fashion houses). He also made regular research trips to Los Angeles, where he purchased vintage denim and casual clothing at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena. Back in the studio, Tulip used the vintage garments had had collected for inspiration. As he recalls, ‘it could be a particular detail, something about the fabric, the fit, the pockets…certain elements would be reproduced somewhere along the line’.

For Tulip, developing a clear concept behind a collection based on thorough research is crucial. ‘It is really, really important to have a thread running through the collection’, he argues, ‘you put your concept and your research together and from that idea you create a garment that you make commercial. That garment then ends up in the store and gets sold and worn’. At Zegna, beyond providing a grounding for the initial idea, a research garment could also function on a practical level. As many designers do, Tulip would develop a technical specification for the new garment and send it to a manufacturer, specifying fabrics, proportions, stitch lines and precise instructions for how to make it. He would sometimes send the research garment directly to the manufacturer, along with the technical sheets. ‘You’d be surprised at the permutations that people manage to create from those notes’, he explains. ‘If you’ve got the actual thing to send them, the job gets done a lot more quickly and precisely’.

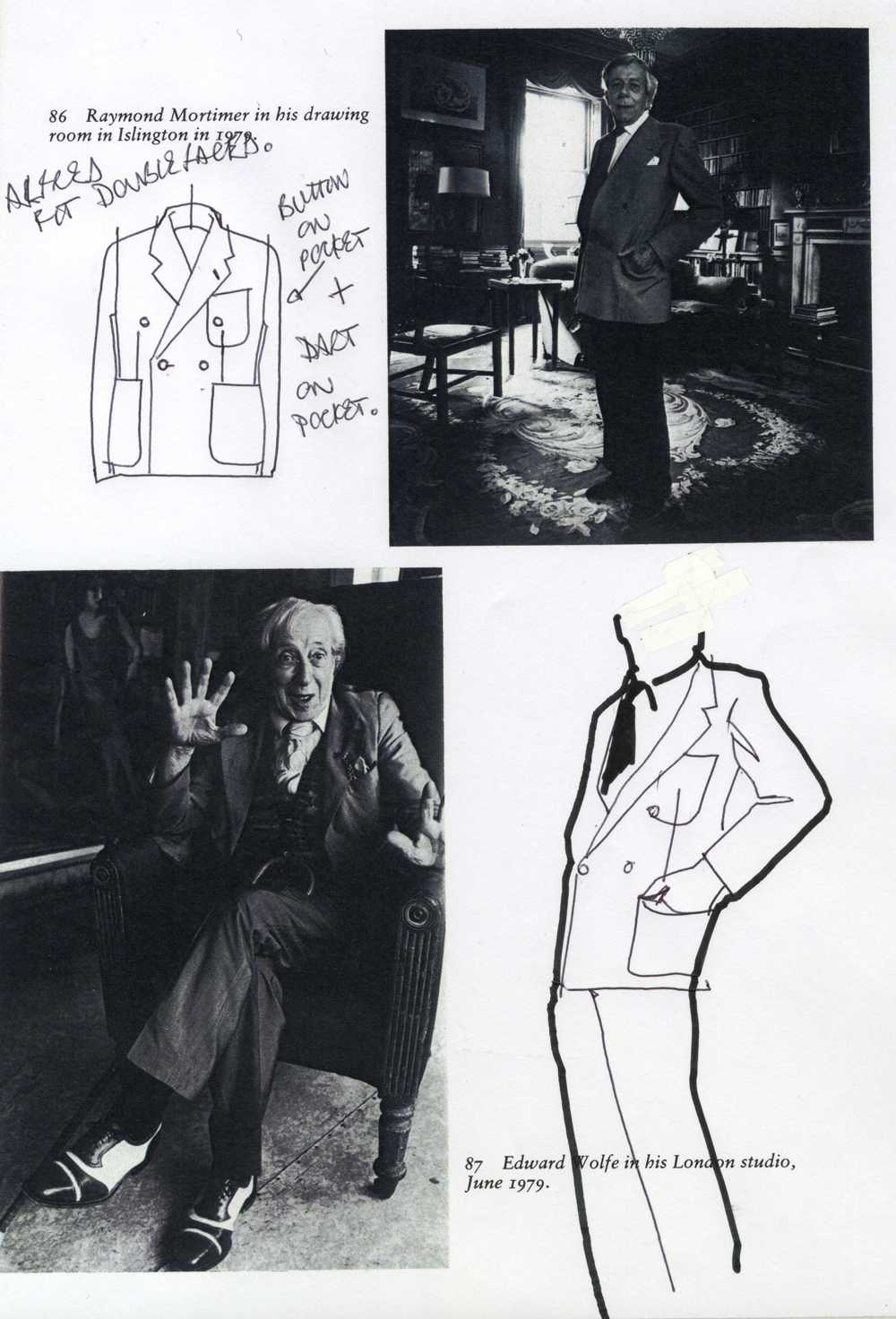

In November 2008, Tulip returned to London to take the role of Senior Designer for the men’s luxury brand Dunhill. The brand’s heritage is central to everything it produces, and behind every collection is a story that relates in some way to the history of the company. Research for Dunhill’s spring/summer 2011 collection focused on the work and lives of members of the Bloomsbury Group. Under the guidance of Creative Director Kim Jones, Tulip and the design team visited Charleston, the home of Bloomsbury Group members Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, which became a meeting place for artists and intellectuals such as Roger Fry, Edward Wolfe and E. M. Forster. The connection to Dunhill was a lighter in the company archive, featuring an image of Dora Maar by Picasso. ‘The idea of Dunhill being linked to that art scene, to that art group, to being relevant as a luxury commodity at that time, in that period, really influenced the collection’, Tulip explains. Through their research, the team built a knowledge base and extensive visual record of the Bloomsbury Group and their work, and they drew on this material to inspire their designs (fig.7).

Dunhill’s autumn/winter 2011 collection will draw on the lives and experiences of the arctic explorers, referencing details of their clothing and lifestyles as pioneers. For their research, the team viewed hundreds of photographs in the Royal Geographical Society archive, using elements of explorers’ garments to inform the design work for their current season. While this research may inform the line of a lapel, the colour palette of a collection or the way a jacket fits, a connection to the brand is essential. ‘The fact that it’s got a link [to the company’s history] brings a significance, a power to it’, Tulip argues.

These historical references enable Tulip and the Dunhill design team to build a narrative behind their new collections – a story which explores the social, intellectual and visual links between, say, a group of innovators like the arctic explorers and Alfred Dunhill, the founder of the Dunhill brand. But the research also contributes to a broader narrative which emphasises Alfred Dunhill’s continued influence on the company’s output, and a triangular discourse between him, today’s Dunhill design team and the references which have inspired the new collections. In a similar way, Stuart Stockdale boosted Pringle’s cultural value by linking conservative golf knitwear with the rebellious image of the teddy boys. By pairing these opposing ideas, Stockdale brought new meaning to the company’s stiff image through the narrative he created, which suggested that the man wearing the golf jumper was a rebel. Like many other London designers, Stockdale’s and Tulip’s use of historic British dress and cultural movements as inspiration gives authority to their work. By helping to promote their Britishness, these references also reinforce their respective brands’ established place in the nation’s cultural makeup.

Beyond using historic clothing as a source for primary research, knowledge of the history of fashion is an important base for many designers. As part of their critical and historical studies, first year MA students at the Royal College of Art attend fashion history lectures. Wendy Dagworthy emphasises the enormous benefit of fashion history in understanding silhouette, cut and materials. This knowledge base becomes particularly important when her students take inspiration from other designers’ work. ‘It’s really, really important to have a good sense of the history of fashion’, Dagworthy argues, ’and to have a sense of what it is that you are referencing’.20 Barry Tulip shares this view. ‘You can’t really design clothes at an influential level without having any knowledge of what has gone before. You just can’t. You have to be aware of what other designers have done and, if you’re referencing something from the past, what the connotations are’.21

This broad awareness of fashion history, together with solid, original and personal research is, in part, what enables some designers to permeate their collections with real meaning. Their ability to take elements of the past to create something new can make a successful graduate collection, produce highly inventive ideas, and even reinvigorate a heritage brand, making it relevant to the modern-day consumer. Surviving garments, whether in museum collections, vintage shops or company archives provide an invaluable lexicon of reference material to draw from. The dialogues these designers create between past and present engender a new set of narratives. Narratives which will, in due course, return to the archives to be re-used by the designers of the future.

Endnotes

-

Frayling, Sir Christopher. Introduction to 60: Royal College of Art Fashion MA Catalogue. London: Royal College of Art, 2008: 1. ↩︎

-

Murphy, D. Future Fashion Now: New design from the Royal College of Art. London: V&A, 2009. ↩︎

-

Interview, Deirdre Murphy with Wendy Dagworthy, August 2010. ↩︎

-

Gordon, Lady Duff. Discretions & Indiscretions. London: Jarrolds Publishers, 1932: 65-6. ↩︎

-

Valerie D. Mendes and Amy de la Haye. Lucile Ltd: London, Paris, New York and Chicago 1890s-1930s. London: V&A Publishing, 2009: 188. ↩︎

-

Hartnell, Norman. Silver and Gold. London: Evans Brothers Limited, 1955: 94-5. ↩︎

-

Hartnell, Norman. Silver and Gold. London: Evans Brothers Limited, 1955: 121. ↩︎

-

Wilcox, Claire. Vivienne Westwood. London: V&A Publications, 2004: 11. ↩︎

-

ilcox, Claire. Vivienne Westwood. London: V&A Publications, 2004: 9. ↩︎

-

Ehrman, Edwina. '"Making Westwood” in Museum of London’, in Vivienne Westwood: a London Fashion. London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 2000: 67. ↩︎

-

Arnold, Rebecca. ‘Vivienne Westwood’s Anglomania’ in The Englishness of English Dress, edited by Christopher Breward, Becky Conekin and Caroline Cox. Oxford: Berg, 2002: 161. ↩︎

-

de la Haye, Amy. The Cutting Edge: 50 Years of British Fashion 1947-1997. London: V&A Publications, 1997: 82. ↩︎

-

About Alexander McQueen (accessed March 2011) ↩︎

-

BBC, British Style Genius (accessed March 2011) ↩︎

-

Bolton, Andrew. Anglomania: Tradition and Transgression in British Fashion. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006: 12-13. ↩︎

-

Interview, Deirdre Murphy with Stuart Stockdale, September 2010. ↩︎

-

Coulson, Clare. ‘A Fabulous Fling with the Fifties’. Telegraph. February 7, 2003 (accessed March 2011) ↩︎

-

Interview, Deirdre Murphy with Stuart Stockdale, September 2010. ↩︎

-

Interview, Deirdre Murphy with Barry Tulip, September 2010. ↩︎

-

Interview, Deirdre Murphy with Wendy Dagworthy, August 2010. ↩︎

-

Interview, Deirdre Murphy with Barry Tulip, September 2010. ↩︎