Abstract

Until the 1920s, the Bethnal Green Branch of the South Kensington Museum contained scientific collections as well as the better-known displays of objects of art and design. This article considers these collections, particularly the ‘Collection illustrating the utilization of waste products’, in the context of the Museum’s early history.

A glass fronted cupboard in a corner of the basement of the Bethnal Green Museum, now the Museum of Childhood, is crammed with small decorative objects – jewellery, boxes, notecases - made from shells, feathers and skins (figs 1–3).

A plastic printed label on the door – ‘Animal Products’ – confirms that what connects these objects is their material origin in the natural world, following the broad and convenient classification into the ‘three great kingdoms’ of animal, vegetable or mineral which underlies the organization of the 1851 Great Exhibition. This classification was applied to the ‘nucleus of a permanent Trade collection’ comprising articles presented to the Commissioners at the end of the Great Exhibition. The items were considered to have potentially ‘great practical benefit for the manufacturing and mercantile communities if systematically arranged for the purposes of reference’.1 With plant products housed at the Museum of Economic Botany at Kew, and mineral products in the Museum of Practical Geology in Jermyn Street, an extensive collection developed from the Animal Products was retained at South Kensington. The background to the Animal Products collection provides a context to understanding the Waste Products Collection, discussed by Pierre Désrochers in this issue of the V&A Online Journal; in one sense, the waste products of manufacture represented a new category of ‘cooked’ raw materials, arising from cultural rather than natural processes, in a world where such neat divisions of material origins were no longer adequate, where chemistry, synthesis and re-synthesis were increasingly important, and where concern about scarcity of materials and growing urban populations drove innovative uses and re-uses.2

The objects in the cupboard are the remnants of curious tributaries in the history of the South Kensington – and hence the Bethnal Green – Museums. They are a reminder not only of its roots in the Great Exhibition but of the original scientific and educational purposes of the founders, often overlooked in narratives of the Victoria and Albert as an institution primarily concerned with taste and design in the decorative arts. As Bruce Robertson argues in his ‘alternative history’, ‘The Museum, in Cole’s vision, was never just a container that staged programs. It was an educational force that deployed material collections’.3 Three long standing exhibitions at Bethnal Green - the Animal Products Collection, the Food Collection, and P. L. Simmonds’ ‘Collection illustrating the utilization of waste products’ - are closely tied together in concept and in the personalities involved. They are a paradigm of a scientific and educational approach mediated through objects and texts, and equally significantly through substances themselves. Underlying the three exhibits is a quantitative approach to the material world, and to the value of its constituents: the Food Collection, for example, was arranged by ‘chemical composition’ on the grounds that ‘all food is found to be composed of the same materials or elements as the human body’, and indeed the exhibit contained a chart showing the composition of the human body by weight of the chemical elements and with those chemical components arranged in ‘jars, trays and saucers’.4

What has survived of the three collections are small decorative items; but also represented in the original displays were industrial and manufacturing processes, bottles and jars of materials and explanatory texts. Few images survive relating to the scientific displays in the museums but an idea of their presentation can be surmised from these and from the registers of objects, catalogues and museum guides. A useful contemporary account of the detail of museum display is given by Thomas Laurie, a manufacturer of museum cases. He proposes in his 1885 booklet Suggestions for Establishing Cheap Popular and Educational Museums of Scientific and Art Collections that ‘material relating to the human body and the laws of health’, for example, could be displayed ‘In an upright glass case, seven feet high, raised one foot from the floor, fifteen feet long, and one foot deep’. Texts should be clear in their educational purpose: ‘Explanations, in simple language, and boldly printed in large type, should form a special feature of all collections’.5

The inclusion of the word ‘cheap’ in Laurie’s title seems significant, intended as it was for new audiences for local museums. Value was a concept that was not only particularly relevant to the Waste Products Collection and to Simmonds’ own exhaustive research into the economics of his wide-ranging interests, but an idea that haunts the wider story of the Bethnal Green Museum: the East End and its people might have been considered only as liabilities or as problems, but for the value of the economic activity concentrated there. The story reflects ambivalence not just towards industry - and those who worked in it - but specifically to refuse, base materials and dirty processes as sources of wealth. As Esther Leslie discusses in Synthetic Worlds: Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry, the natural cycle of growth, decay and reproduction had been thrown into asymmetry by the growth of towns and industry, and she quotes Marx’s proposition of a new, man-made cycle: ‘capitalism teaches how to throw the excrements of the processes of production and consumption back again into the circle of the process […] and thus […] creates new matter’.6 This ambivalence was also epitomized in Dickens’ last novel Our Mutual Friend (1865) with its recurring themes of salvage; the soiled fortune from waste collection which holds the complex plot threads together, represented by a landscape of the ‘mounds of dust’ from which the wealth was extracted (fig. 4).7

Like Dickens, the founders of the Bethnal Green Museum believed in the redeeming and improving power of education for the working classes, but there was an ultimately irreconcilable difference of opinion about whether this could best be done through association with precious objects of high culture or by deepening understanding of more mundane aspects of the material world, particularly those of immediate relevance to the audience in their daily working lives.

When the South Kensington Museum came to dispose of the iron buildings known as the ‘Brompton Boilers’ from the site of the 1862 exhibition, the buildings were to be offered ‘in portions’ to London districts expressing the wish to see local museums established. The origins of the Bethnal Green museum typify Anthony Burton’s phrase ‘vision and accident’ to describe the history of the Victoria and Albert Museum; the vision being to establish museums in parts of London where working class people could benefit from their educational purpose.8 That attention to the education of adults from the working classes was clearly linked in the thinking of the time to the fitness and competitiveness of British industry is confirmed by supporting statements before the House of Lords debate on the setting up of the museum: ‘unless our working people in this country are educated we will not be in a position to maintain that supremacy in commerce and manufacture upon which all our other supremacy is based’. The huge popularity of newspapers and periodicals was cited as evidence of the current ‘disposition amongst the working classes of this country to be enlightened’.9

In the event, only the Bethnal Green district came up with a proposal for using the buildings. The accident was the fortuitous availability of a large site in Bethnal Green which was ‘useless and unprofitable’ since it was used for grazing, being held by a charity as open space– hence having no commercial value despite its location in a densely populated area. According to one commentator, who described the Bethnal Green Museum as an ‘asylum for South Kensington refuse’, these displays, like the buildings themselves, were thought to have reached the end of a useful life at South Kensington and to be ready for disposal.10 As such, these exhibits may have been considered to be particularly appropriate for a working class audience.11 The museum was thus already a recycling project, viewed with suspicion by some critics; the Galway MP William Gregory suggested that ‘if [the South Kensington] authorities were allowed to transfer the overflowing and sweepings of Kensington to other parts of the country, there would be no check upon their extravagance’.12 As well as the building, the collections of Food and of Animal Products were similarly relocated from South Kensington: ‘There are one or more classes of objects in the South Kensington Museum which would appropriately constitute the foundation of such a museum, such as the collections of animal products useful in manufactures’.13

As Désrochers points out, Simmonds’ Waste Products Collection, added three years after the museum’s opening, was a similar blend of a cabinet of curiosities, classroom and showcase for industry, following in the catalogue the three broad categories of substances derived from vegetable and animal origins and from sewage and mineral waste.14 Visitors were presented with a huge range of exhibits, from decorative items from other cultures to examples of the latest applications of industrial chemistry, with descriptive labels explaining processes and estimating their potential economic value. As well as a generally instructive purpose, one thought was that museums should be location-specific: ‘in every district of London there ought to be a branch museum established, adapted to the particular trades of the locality in which it is established’.15 The 1860 regulations for contributors submitting exhibits for the Animal Products Collection make clear that, as in the Great Exhibition, there was a strong commercial element to the displays: ‘Descriptive labels will be attached to the various contributions, giving their names, uses, prices, &c’, and thus that the relationship between exhibitors, visitors and proprietors could be more complex and interdependent than merely a top-down educative project. Labels and catalogue descriptions helped to situate the manufactures and processes on show, and as much as passive observers, the visitors could equally have been involved in production or consumption of articles on display.16 Yet, one commentator on the International Exhibition of 1872 criticised that approach as ‘scarcely removed in their aspects from the factory and workshop life from which an escape is needed’, significantly ignoring the scientific displays in referring to Bethnal Green Museum’s early success as a ‘really admirable art-museum’ and reflecting that what the ‘thing really wanted is a scheme for placing worthy objects of interest in fairly attractive buildings in various quarters of our great metropolis’.17

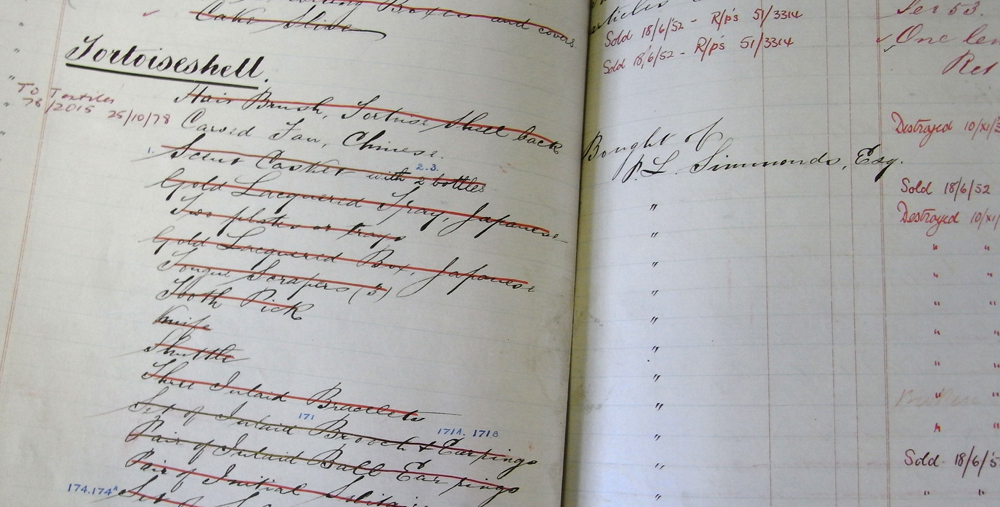

The collections of Animal Products and of the Utilisation of Waste Products were also linked through Simmonds - an inveterate collector himself - who ‘took a not inconsiderable part’ in setting up the Animal Products Collection with Lyon Playfair in 1857. He wrote descriptive catalogues for the collection and indeed provided many of the exhibits, as the registers of objects show (fig. 5).18

Many of Simmonds’ donated items from shells, for example, are among those which still remain in the V&A collections. The content of both demonstrated a vision of the world as raw material and economic resource that should be exploited as inventively as possible. Indeed, one division of the Animal Products Collection already covered waste - Class V, the ‘application of waste matters’ was set out as follows:

- Div I Gut and Bladder

- Div II albumen, casein &c

- Div III prussiates of potash and chemical products of bone etc.

- Div IV animal manures, guano, coprolites, animal carcases [sic], bones, fish manures etc.

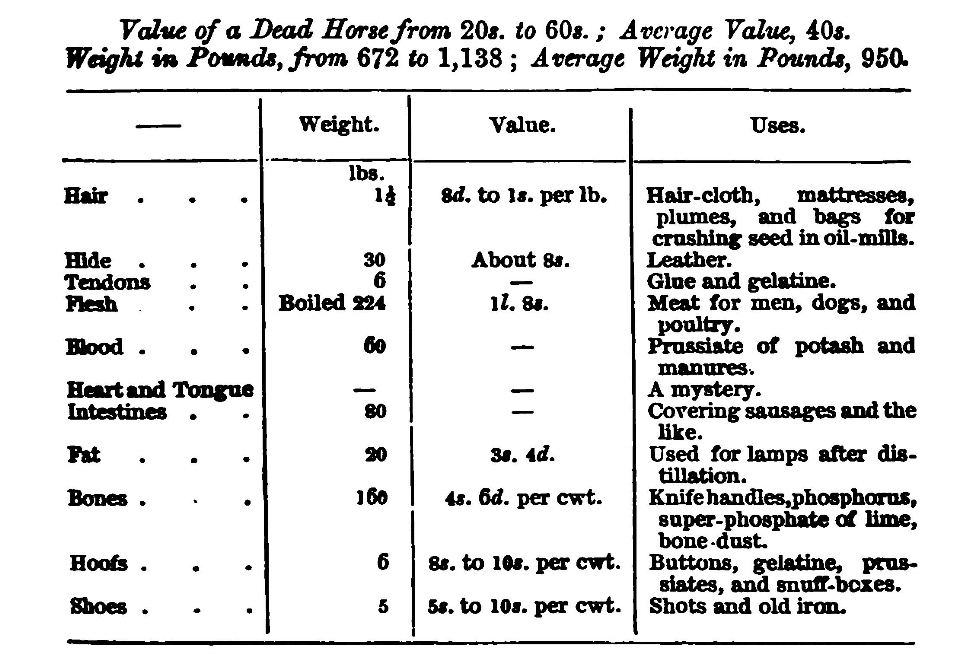

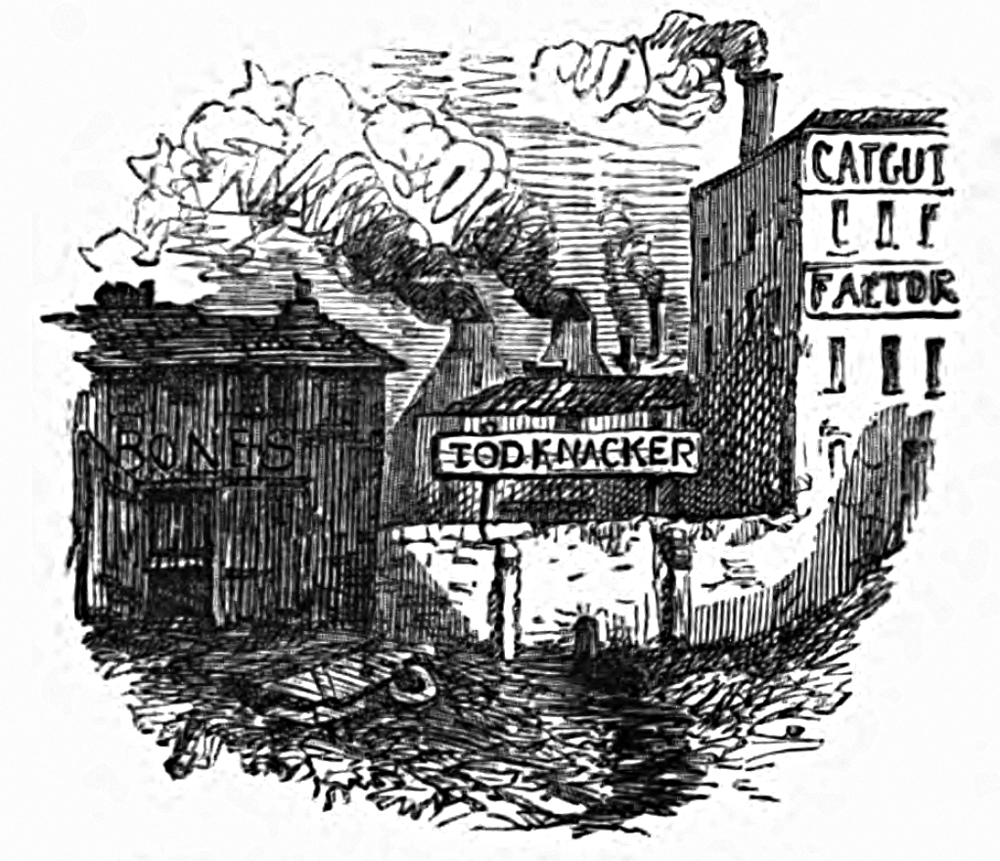

This class in the collection persisted throughout the life of the Waste Products exhibition, despite the apparent overlap in subject matter once that was installed.19 A table from the Animal Products Collection showing the uses and value of a dead horse, is characteristic of the preoccupations common to both - to quantify commercial value and to demonstrate the ingenuity of industry - and a very similar description appears in the Waste Product Collection with the added invitation that ‘those curious to see the whole process may pay a visit to Green Street, Blackfriars, or Wandsworth and other localities where horse slaughterers are located’.20 The chart of the horse’s components, reproduced here from The Uses of Animals in Relation to the Industry of Man by Edwin Lankester, is shown in the register as being ‘revised and reprinted’ in 1872 (figs 6–7).21

In itself an example of the recycling of a useful idea, the deconstructed dead horse can be traced back through a note added to Babbage’s Economy of Machinery and Manufacture by its German translator in 1833.22

A description of the uses of animal guts in Animal Products illustrates how the displays used text and objects. In case 312 ‘exhibited by Mr F. Puckridge of Kingsland Place’ (in Hackney) is an explanation of the process of making ‘gold beaters skin’ from the membrane covering the intestine of the ox (fig. 8).23

Gold beaters’ skin was used to interleave thin-rolled sheets of gold which were then beaten out to form gold leaf:

- A bottle, with the raw skin in the wet state, as obtained from the ox; being the outer membraneous covering of the gut.

- the same dried.

- the skin as prepared in frames for varnishing.

- goldbeaters’ skin finished as used by druggists.

- A goldbeaters’ mould, with sheets of skin containing 850 leaves, each leaf being double, making 1700 thicknesses, used to beat out gold leaf.

- A goldbeater’s shoulder, as used in the second process of goldbeating.

- A silver mould and book of leaves, used to beat out silver from the size exhibited to the size of the mould.

- A heavy goldbeater’s mallet, weighing 8 ¼ lbs.

The product was valuable, ‘often fetching ten guineas per mould of 850 small leaves’, and evidently Puckridge’s business was thriving as it was said to consume the guts from 10,000 oxen a week.24 It is an extreme example of the alchemy of industry refining such an apparently base material – the ‘raw skin in the wet state’ into a valuable commodity through association with gold itself. A comment by Charles Knight in his Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge that this industry belongs to an ’exceedingly dirty and disagreeable class of manufactures’ is, however, a reminder that industries using waste were among the most noxious in themselves (fig. 9).25

Images showing the Food Collection while still at South Kensington and a detail from the opening of Bethnal Green Museum give at least some idea of how the exhibits for the scientific displays were laid out overall, using a combination of frames, glass cases and substances in jars ‘ranged on shelves over the counter’ (figs 10–11).26

The displays were evidently generously labelled with text. An article about a Bank Holiday at the Museum in Chassell’s Family Magazine in 1883 approvingly describes local visitors to the Food Products display giving time to the labels: ‘it was worth remarking, too, that as a rule the visitors did not content themselves with any mere cursory glance at the cases, but passed along the lines of bottles, and slowly deciphered their inscriptions in a way indicative of a thoroughly aroused interest’.27 An illustrated publication about the Animal Products was produced in 1880 to meet the demand for ‘popular scientific information’,

‘The brief descriptive framed labels of the Animal Products collection in the Bethnal Green branch museum, prepared by Mr. PL Simmonds, are found to be much studied, and many have frequently been copied by visitors. […] To meet this demand for popular scientific information the Lords of the Committee of the council on education have directed these labels to be reprinted, in a collected and cheap form, with merely an occasional alteration of figures[…] and the additions of some woodcuts’.28

This book is in a larger format than the catalogues, with larger and briefer text and a profusion of illustrations, mostly of the animals themselves. The demand for the product raises the interesting question of whether the performative aspect of a museum, where the visitor moves through taking in smaller units of information with visual prompts, had itself influenced the production of texts of popular science. As suggested by the publication of books of lectures on the Food and Animal Products collections by Edwin Lankester (who according to one reviewer was known for ‘bringing abstruse matters into a simple form’) there were a number of ways in which the museum might mediate knowledge to a wider audience both directly and indirectly.29

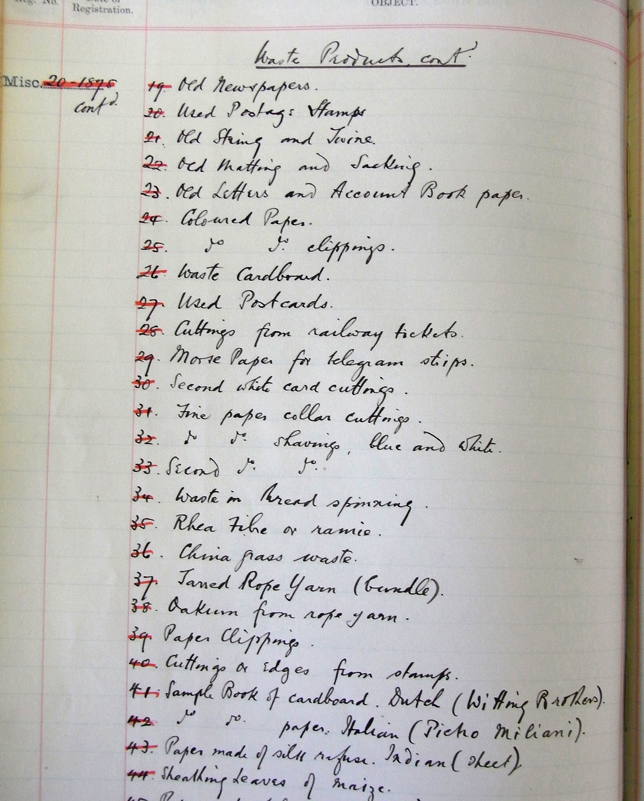

On examining the register of the objects Simmonds supplied for the Waste Products exhibition it is striking how, in addition to the texts and objects of manufacture, materials themselves were produced as evidence. The catalogue lists 51 categories of entry with a total of nearly 1,000 objects ranging from 43 items under ‘silk waste’ to old bus tickets (fig. 12).30

Over 600 jars are logged as arriving at the museum, containing everything from sand to human faeces (three different proprietary processes for transforming sewage into fertilisers were represented). Even in glass jars their particular qualities would have been obscure; but the quantity of them suggests that Simmonds must have felt that their presence as ‘real things’ was essential rather than illustrative, to be supported by text rather than the other way round. Unlike objects and artefacts made of durable materials, however, or the well-behaved mineral division of the natural world, this organic matter had a limited shelf-life. The register records a series of removals with the terse comment ‘decayed’. One wonders what the display must have looked like– and possibly even smelt like - when the next batch of removals became necessary. It has to be said, too, that Simmonds’ magpie enthusiasm for the subject made it a very elastic concept, allowing him to wander outside the realm of industrial by-products - materials that are already ‘cooked’ in some way - into examples of interesting uses from raw materials of all kinds. Simmonds’ own words when he was asked to report on the collection in 1891 with a view to updating it suggest that he was aware of these problems: ‘Animal and Vegetable Wastes, necessarily deteriorate, and become unsightly – the difficulty I experience is as to where to draw the line – between the utilisation of the residues of Manufactures, and the development of neglected products, which until used are certainly waste substances’.31 The list of objects in the receipt on the file for 22 July 1875 reads as if he might have gathered them from a forgotten corner of his attic:

22 July 1875

78 Bottles containing Illustrations of Waste products

10 articles -as per list attached [list reads: ]

1 small piece of cork matting

1 Straw photo frame

1 Pair horse hair socks

1 small Brick

1 Piece esparto grass

1 Wooden Idol, one ear missing, much broken

1 Small Box with date stones etc

1 Small model of a Bark Canoe, both ends broken one small piece lost

1 piece imbira cheirosa for rope making Brazil

1 small tin with sand from Senna Green’.32

Reading this list, it is not difficult to understand why R. A. Thompson, the Assistant Director of the museum, noted on the file in 1891 that ‘another edition of the Catalogue is wanted, but I cannot recommend Mr Simmonds to do it. He might be employed to add to the Collection any waste products that are new but many of the specimens already there are not waste products’.33 In 1897, when a manufacturer of ‘silicate cotton’ who had provided samples wrote to enquire if they should update their exhibit as it was no longer ‘very presentable’, a file note reads ‘If the Waste Products Collection is to be kept up I think it would be well to accept this offer’, suggesting the future of the collection was already in doubt.34 In the 1920s, under the head curator Arthur Sabin, the museum was gradually reorganised and the collections of Animal and Waste Products and Food removed from display.35 The collections had been reviewed by the Director of the Science Museum, who ‘considered that nothing in them could be of the slightest use to the Science Museum’. The Animal Products collection was said to have ‘scattered throughout its bulk many objects of minor interest’. These decorative items, textiles and clothing were removed to other departments or still survive in the Bethnal Green Animal Products cabinet. Some ‘miscellaneous’ items from the Waste Products collection were retained but the remaining items, ‘a great bulk of quite useless and valueless material’ according to Sabin, contained ‘nothing of intrinsic value whatever, whilst the state of most of it is such that its early destruction has become imperative’. A Board of Survey was appointed to review objects for disposal which Sabin judged ‘entirely foreign to the present purpose (or any conceivable future purpose) of the Museum’. Having duly inspected 1600 items, of which some materials such as oils and lac were retained for use by the Art Workroom (the V&A’s conservation department), the Board reported that the remaining items comprised ‘small specimens of various materials which have absolutely no value of any kind’.36

How was it, then, that the aspects of these scientific collections which represented some of the most advanced applied science of their time, had come to be viewed so negatively; as not only worthless but actively threatening to the health of the museum? In part it is a reflection of a lack of direction of the Bethnal Green Museum in its early years; the image of the museum as itself something of a cast-off persisted. Anthony Burton quotes a report from the Daily News as early as 1879: ‘It is grievous that an institution established with the best of intentions and successfully launched should be allowed to dwindle into a mere refuge for specimens and spectators who have no other place in which to find rest and shelter’.37 With the Science Museum’s move for independence at the turn of the century, leaving the V&A as an art museum, these exhibits were increasingly anomalous, and as permanent collections, it had perhaps been too easy to overlook them as part of the fabric of the museum without reconsidering their role. Increasingly, a visit to the Museum was described more in terms of the merits and intrinsic interest of individual objects than the thematic links of their origins - for example, the Animal Products collection was interpreted in one account as clothing: ‘the covering of the outward man’.38 In 1891 the Brief Guide to the Collections described the waste products display as ‘instructive and interesting’ but as a list of materials rather than a concept: ‘waste cotton, waste jute, coco-nut, mosses, seaweed etc, waste nuts, seeds, flax straw, &c: waste wood, rattans, barks, leaves &c; waste paper, oil-cake, rags &c; waste silk, vines, leather, feathers, &c; tanners waste, gut hair fish, &c; waste shale &c; glass and metallic waste, coal tar &c’. It was not mentioned at all in the 1904 edition and with the briefest note in 1908 as being between a collection of medals and a Roman coffin.39 ‘New matter’ in the form of world-changing substances such as aniline dyes and artificial fertilisers were included in the displays; but left unattended over the years and without an enthusiastic programme of re-interpretation, they must have seemed outdated and mundane, even disgusting, compared to the riches of paintings, sculpture and other artifacts with which they competed for visual attention.

Endnotes

-

Catalogue of the Animal Products Collection. London, 1857. ↩︎

-

See Lévi-Strauss, Claude. The Raw and the Cooked. New York: Harper & Row, 1969 (tr. John and Doreen Weightman) for the origin of this dualism. ↩︎

-

Robertson, Bruce. ‘The South Kensington Museum in context: an alternative history’. Museum and Society. 2 (2004): 9. ↩︎

-

Inventory of the Food Collection. HMSO, 1869: 53; Guide to the Collections of the Bethnal Green Branch. London, 1872. This information represented very current research into the composition of the human body related to the composition of foodstuffs. See ‘History of the Study of Human Body Composition: A Brief Review’. American Journal of Human Biology. 11 (1999): 157–165. ↩︎

-

Laurie, Thomas. Suggestions for establishing cheap popular and educational museums of scientific and art collections and industrial productions and inventions in all towns, villages and districts and also for their classification, arrangement and exposition on a new plan, making them available for pupils in lower and middle class schools and colleges, mechanics’ institutes, science and art classes, and for the instruction and recreation of the general public. London: T. Laurie, 1885. ↩︎

-

Leslie, Esther. Synthetic Worlds: Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry. London: Reaktion, 2005: 83. ↩︎

-

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. London: Chapman and Hall, 1865. See also other accounts of the value to be found in waste in ‘Dust – or Ugliness Redeemed’. Household Words. 1850: 379, which Dickens was said to have used as an idea for Our Mutual Friend; ‘Filthy Lucre’. Good Words. 20 (1879): 741. ↩︎

-

Burton, Anthony. Vision and Accident: the story of the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: V&A, 1999. ↩︎

-

Evidence of Thomas Conolly, described as ‘a working man’. Correspondence etc. relative to the establishment of the East London Museum. 1872: 18. Collection of Bethnal Green Museum. ↩︎

-

Kriegel, Lara. Grand designs: labor, empire, and the museum in Victorian culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008: 182. ↩︎

-

The other collection mentioned as being desirable to include was ethnography from the British Museum. In the event Pitt Rivers supplied ethnographical items which were displayed in 1875, the same year as the Waste Products Collection: see extract from W. R. Chapman, Pitt Rivers and his collection. 1984, reprinted as ‘Bethnal Green and South Kensington Museums’, https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/Kent/musantob/betsken.html (accessed 15 January 2011). ↩︎

-

Hansard. August 10th, 1867: 1298. ↩︎

-

Correspondence etc. relative to the establishment of the East London Museum. 1872: 18. ↩︎

-

See V&A Museum of Childhood, Miscellaneous Register, 1871–1921: Descriptive Catalogue of the Collection illustrating the utilization of Waste Products. Bethnal Green Museum. London: HMSO, 1875. ↩︎

-

Evidence of Mr Conolly: Descriptive Catalogue of the Collection illustrating the utilization of Waste Products, 18. ↩︎

-

Catalogue of the Collection of Animal products. South Kensington Museum, 1860. ↩︎

-

Penny Illustrated Paper and Popular Times, 26 October, 1872. ↩︎

-

Simmonds, Peter Lund. Animal Products; their preparation, commercial uses, and value. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877. ↩︎

-

Catalogue of the Collection of Animal Products. South Kensington Museum, 1860: 109.9 ↩︎

-

Waste Products Catalogue. 47. ↩︎

-

Lankester, Edwin. The Uses of Animals in Relation to the Industry of Man; Being a course of lectures delivered at the South Kensington Museum. London: Robert Hardwicke, 1860. Lankester was at the time Superintendent of Science at the South Kensington Museum. See also V&A Museum of Childhood, Register of the Animal Products Collection. ↩︎

-

Babbage, Charles tr. Dr G Friedenberg, Über Maschinen- und Fabrikenwesen. Berlin: Verlag der Sturschen Buchhandlung, 1833. ↩︎

-

A gain, a description of goldbeaters’ skin also appears in the Waste Products catalogue: 42, but relates to a much smaller exhibit from a different manufacturer. ↩︎

-

Catalogue of the Collection of Animal products. South Kensington Museum, 1860. ↩︎

-

Knight, Charles. The English Cyclopaedia: A new Dictionary of Universal Knowledge. Volume 4. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1860: 437. ↩︎

-

Catalogue of the Collection of Animal products. South Kensington Museum, 1860: 111. ↩︎

-

Cassell’s Family Magazine, 1883. Tower Hamlets Library collection. ↩︎

-

Commercial products of the animal kingdom employed in the arts and manufactures shown in the collection of the Bethnal Green Branch of the South Kensington Museum. (briefly described by P. L. Simmonds, with more than 150 illustrations). London: HMSO, 1880. ↩︎

-

‘Review of The Uses of Animals in Relation to the Industry of Man’, in Medical Times and Gazette. Nov.17, 1860: 485. ↩︎

-

This appears to be another overlap with the animal products exhibit. Making threads from silk waste, short or damaged fibres which would previously been thrown away, was now a thriving industry. See Simmonds, Commercial products of the animal kingdom. London: HMSO 1880: 92. ↩︎

-

V&A Archive, MA/2/B20, nominal file: Bethnal Green Museum, Waste products Collection. ↩︎

-

V&A Archive, MA/2/B20, nominal file: Bethnal Green Museum, Waste products Collection. ↩︎

-

V&A Archive, MA/2/B20, nominal file: Bethnal Green Museum, Waste products Collection. ↩︎

-

V&A Archive, MA/2/B20, nominal file: Bethnal Green Museum, Waste products Collection. ↩︎

-

V&A Archive, MA/50/2/12, Policy file: Bethnal Green Museum Board of Survey. ↩︎

-

V&A Archive, MA/50/2/12, Policy file: Bethnal Green Museum Board of Survey. ↩︎

-

Burton, Anthony. Vision and Accident. 120. ↩︎

-

Cassell’s Family Magazine, 1883. Tower Hamlets Library collection. ↩︎

-

A Brief guide to the various Collections in the Bethnal Green Branch of the South Kensington Museum. London: 1891, 1904, 1908 editions. ↩︎