Abstract

Good public spaces accommodate, and attract, lingering. National museums in the UK are civic spaces, where seating is provided in circulation areas for visitors to wait, rest or otherwise pause. Different areas and kinds of seating support a range of uses by visitors in addition to sitting. A pilot study conducted in late 2009 investigated three circulation areas in the V&A - the Grand Entrance, Grand Entrance Steps, and the Sackler Centre reception, to explore how these spaces and the styles of seating provided are used by museum visitors. The study shows that differentiated spaces with varied styles of seating are an important aspect of the Museum’s visitor provision.

‘Seating is an explicit invitation to stay, either with others or by oneself’1

Seating in public spaces is an easily overlooked aspect of our urban environment as we go about our daily lives, yet we use public seating for all sorts of reasons – to rest our feet, wait for a friend, eat a sandwich or tie a shoelace. Seating gives us a reason to pause and rest. National museums in the UK – the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) included – belong to the diverse spectrum of spaces which make up the public realm. We may not immediately consider museums to be ‘public’ in the same way as streets or parks – museums have thresholds, security staff, few issues with ‘anti-social behaviour’, and access is structured around opening hours. However, it is also true that the external public realm is not the openly accessible place we would ideally expect it to be. Much the same as entering a train station with a ticket or a café with an order of coffee, entering a museum is a contractual gesture – we may view the obligatory bag check on entering the Museum as the signing of an unspoken agreement between visitor and building. Museums have the remarkable privilege of being public spaces with access enough to allow visitors to move about freely, and invigilation enough to prevent damage to the building fabric.

In Civilising the Museum, Elaine Gurian draws on the early planning theories of Jane Jacobs to advocate for greater emphasis on the civic role of museums, pointing out that museum visitors spend a large portion of their time doing something other than engaging with exhibits or programmes.2 Comparing museum interiors to ‘streetscapes’, she suggests that what Jacobs calls ‘ad hoc’ use, ‘seemingly unprogrammed social activity that arises within public space’, is of great value to museums, and that simple gestures to support this activity - such as the provision of free seating - greatly enhance the welcome of the museum.3 Gurian cites Jacobs’ argument that ‘formal public organisations in cities require an informal public life underlying them, mediating between them and the privacy of the people of the city’.4 In ‘non-programmed’ areas in the museum, such as foyer spaces or thoroughfares, seating allows visitors to pause and rest, but it is also an invitation for them to stay – which, as we will see, is a starting point for other uses.

The presence of people in public spaces has long been considered an important indicator of a healthy public life. Danish architect and academic Jan Gehl, one of the most influential researchers of public space in Europe in the 20th century, regards lingering (not to be confused with the more pejorative ‘loitering’) to be the key indicator of how well a public space is working, because it shows that a space offers enough interest (something to watch) and comfort (somewhere to sit) for people to choose to spend time there. Gehl regards seating as one of the most important provisions in public spaces to encourage lingering, because ‘[o]nly when opportunities for sitting exist can there be stays of any duration. If these opportunities are few or bad, people just walk on by’.5 In outdoor spaces, weather plays a decisive role in how attractive a space may be on any given day. Because of this, one of the key indicators used by Gehl Architects in studies of cities around the world is whether or not a space shows a large discrepancy in use between winter and summer months.

Often, it is other people that provide the main attraction in public spaces. Gehl argues that, ‘compared with experiencing buildings and other inanimate objects, experiencing people, who speak and move about, offers a wealth of sensual variation’.6 Gurian calls this desire to be around others ‘congregant behaviour’. She writes, ‘we human beings like to be, and even need to be, in the presence of others. This does not mean we have to know the other people or interact directly with them. Just being in their proximity gives us comfort and something to watch’.7 Jane Jacobs writes extensively on the importance of ‘people watching’ in public spaces, arguing that, quite apart from an enjoyable pastime in itself, ‘people-watching aids in [producing a sense of] safety, comfort, and familiarity for all’.8

In the early 1980s, American urbanist and researcher William Whyte studied a selection of New York’s outdoor plazas and their patterns of use by the public, in order to find out why some were lively and busy while others languished in disuse. After much trial and error analysing a series of variables such as the availability of sunshine or the amount of open space, Whyte discovered a relationship between the amount of ‘sittable’ space in any given plaza and how popular it was as a place to spend time in, concluding his analysis with the apparently obvious insight that ‘people tend to sit most where there are places to sit’.9

Whyte was careful to include ‘integral’ seating in his research, which he defined as ledges or steps that were not overtly designed for sitting, but which were appropriate for the purpose nonetheless. Indeed, integral seating can play a very practical role in cities. Some of the liveliest public spaces in cities around the world are the steps of civic buildings, used by visitors to these institutions and non-visitors alike. Architectural critic Paul Goldberger observed, ‘[t]here are some stairs in the city - like those in front of The Metropolitan Museum of Art… that are arguably more important urban events than the buildings to which they lead’.10

The V&A has two excellent examples of outdoor integral seating: the deep stone edges of the pond in the John Madejski Garden, which are particularly well patronised in the summer months for sandwich-eating and people-watching, and the Grand Entrance steps leading into the Museum from Cromwell Road, which are similarly well-used, with the added benefit of being accessible to the public (visitors or otherwise) even when the Museum is closed. Integral seating is an effective way to balance commercial café seating with free seating in outdoor areas, however, it should be noted that integral seating places a high demand on the sitter, and tends to be avoided by people with mobility impairments. Gehl Architects’ 2004 report Towards a Fine City for People pointed out that London’s streets were seriously lacking in quality public seating, and that in the context of the city ‘[a] high level of [integral] seating is a symptom of a benchless city – a city without seats’.11 Lack of seats means a lack of opportunities for staying, so the urban realm becomes little more than a thoroughfare. Indeed, another key finding in Whyte’s research is that ‘circulation and sitting… are not antithetical but complementary’, and should therefore not be separated through urban design.12 A lively public space needs to invite people to linger, as well as allowing them to pass through.

The Grand Entrance is the most-used and most central threshold to the Museum, connecting major galleries and the Museum Shop, as well as providing services such as ticket sales, general enquiries and a designated meeting point for gallery tours. The Grand Entrance interior was redesigned by Eva Jiricna Architects as part of Futureplan (completed 2003) to create ‘a brighter, more welcoming arrival point for visitors’ and to rationalise circulation through the space.13 The architects designed curved, bench-like seating for durability and ease of movement – to accommodate both sitting and circulation. The benches have accompanying round tables, which can also be used as seats. Bespoke seating is custom-made for a specific area – these are one-off designs that will not be repeated or used in other contexts.

As a precursor to a larger body of research into public space in the V&A, in late 2009 a pilot study was conducted to see how three different circulation areas with contrasting styles of seating were used by visitors to the V&A, over a period of approximately three weeks; the Grand Entrance (interior), the Grand Entrance Steps (exterior), and the Sackler Centre for arts education reception area (interior). These areas have contrasting styles of seating, which can be described as ‘bespoke’, ‘integral’ and ‘mass-produced’ respectively. Every fifth visitor who entered the seating areas was observed using tracking sheets, creating data for people who sat down and people who either remained standing or did not pause at all. For each observation, the route taken by the visitor was tracked and the amount of time they spent in the seating area was recorded. The activity they displayed while in the seating area was also noted, including any interaction, whether directly with other people or indirectly via a mobile phone.

The Grand Entrance Steps mediate the Museum and the street and are subject to changes in weather and season. This area was chosen for the study as an example of integral seating, and it is the only outdoor location in the study. The Grand Entrance steps were redesigned (also as part of Futureplan) by PRS Architects with the express purpose of accommodating disability, which the architects achieved by a long, gentle incline favourable to wheelchairs and low-rise steps favourable to all users, including sitters.14 Consultants for the project advised that people who use walking sticks often find steps an easier task than slopes, so both were used in the design. Significantly, the architects wanted the steps to be ‘a place for people to meet each other, write postcards, and generally hang out’.15 In the early stages of the project there was some discussion about not having steps at all, in favour of slopes, but it was universally decided that the steps were necessary – not only as an alternative means of entry to a slope, but as a sociable space. It was felt that handrails would hamper sociability, so only one was installed – at the midpoint of the steps.

A relatively new space in the Museum, the Sackler Centre was completed in mid-2008. Designed by Softroom, the space is a dedicated education centre over two levels, incorporating a series of studios on the lower level and seminar rooms, artist-in-residence studios, and a gallery space on the upper level. The Sackler Centre is located at the base of the Henry Cole Wing, below street-level to the rear of the Museum. It is most easily reached via the Exhibition Road Groups entrance and the Tunnel Entrance, and serves as a thoroughfare between the Exhibition Road entrances and the Café, The Robert H N Ho Buddhist Sculpture Gallery and Ceramic Staircase. The Sackler Centre was chosen for the study as an area with ‘mass-produced’ seating, which means it is made by factory processes and is commercially available. The reception area in the Sackler Centre features a number of contemporary designs by Ron Arad (MT1 chair), Simon Pengelly (hm85a chair) and David Chipperfield (hm991k daybed). This was the only space in the study with moveable or swivel seating, as well as the only space with soft seating.

Findings of the study

After the pilot observations, categories of visitor behaviour were developed for ‘Sitters’ and ‘Non-sitters’. Many activities were common to all spaces, such as waiting, idleness, reading; and some were particular to a space – such as looking at the Dale Chihuly chandelier in the Grand Entrance, and smoking on the Grand Entrance Steps. An early finding of the study was that ‘waiting’ was distinct from ‘being idle’, as people who were ‘waiting’ tended to be ‘waiting for someone’. A person who may have appeared ‘idle’ initially was considered to be ‘waiting’ if that person then met a friend in any given space. People who were observed to be ‘idle’ did not show any significant activity or interaction throughout the observation.

Visitor activities common to all spaces (Sitters and Non-sitters)

- Waiting

- Being idle

- Interacting with friends or strangers (‘direct interaction’)

- Interacting using a mobile phone (‘indirect interaction’)

- Reading

- Writing

- Adjusting clothing

- Looking in or resting a bag on the seats

- Yawning (‘fatigue’)

- Personal (such as nose picking, kissing, or on one occasion, pulse-checking)

- Eating or drinking

- Pausing (to collect leaflets, look in a bag, look at a sign, etc.)

Visitor activities specific to spaces (Sitters and Non-sitters)

Grand Entrance

- Looking at the Dale Chihuly Chandelier

Grand Entrance Steps

- Smoking

- Using the ends of the steps in a ‘stepping stone’ fashion

- Dancing

Sackler Centre

- Holding a meeting

- Touching a chair

- Using a laptop

Figures 1–6 below illustrate the variety of activities Sitters and Non-sitters were observed to engage in for each space in the study. Activities are recorded by number of times observed. For example, a single visitor may read, interact and take a photograph during the course of an observation.

The study found that seating areas are used for many different purposes, for which sitting is only a starting point. Unsurprisingly, the study confirmed Whyte’s observation that ‘people will tend to sit where there are places to sit’, though, as the tables indicate, there were differences in how the seating areas in each space was used by visitors. The average sitting time for the Grand Entrance was 4 minutes 91 seconds, compared with 3 minutes 89 seconds in the Sackler Centre, and 17 minutes 27 seconds for the Grand Entrance Steps. To take Gehl’s argument that the duration of stays is important because activity in public space is self-reinforcing, it would appear that the Grand Entrance Steps are the most effective of the spaces in the study.16 However, it should be noted that the 17 minute figure is based on only two Sitters, whereas the sitting durations in the interior spaces are based on 27 Sitters in the Grand Entrance, and 25 Sitters for the Sackler Centre. The longest stay observed in the Grand Entrance was 21 minutes and 10 minutes in the Sackler Centre. So, the average sitting time cannot be relied upon to give an accurate picture of lingering in each space, indeed, there was evidence of both fleeting and extended stays in the interior spaces.

In the Grand Entrance, Sitters were most commonly observed to be reading, interacting and looking through their bag. This was also the area with the most evidence of people simply lingering in the space as well as the area with the most varied activity. The Grand Entrance seating areas were very much linked to the wider V&A, providing visitors with current marketing material, acting as a meeting place for the start or end of a visit, a place to don hats or coats, as well as the designated meeting place for guided tours. There was plenty of activity in the space to watch – people walking by, joining a queue, talking, taking photographs. Most people chose to look into the centre of the space from the seats, and would only use the wall-facing side of a seat during busy periods. At particularly busy times, younger visitors were observed to use the pillars in the Grand Entrance as impromptu seating – though these structures would not generally be considered integral seating, they did provide an apparently attractive opportunity for leaning. Sitters would generally display a range of activities throughout each observation. One visitor in the Grand Entrance used a bench to take off his jacket, look through his bag, rest his feet on the seats and eat a packed lunch.

The most commonly observed activities on the Grand Entrance Steps for Sitters were outdoor activities (such as eating, smoking, putting on coats or hats) and interaction. This was the only space in the study where Sitters did not appear to be waiting or idle; the Steps appeared to be a destination in themselves, unlike in the interior spaces where seats appeared to be used at different stages of a visit. The integral seating was definitely the most casual of all spaces and invited the longest stay. Though only two people were observed to sit down in the study, both were observed around midday in fine weather, and both used the steps to smoke and eat a sandwich. The small number of Sitters observed on the Grand Entrance Steps should not be considered a failing, especially considering the long duration of each stay. The study was conducted in late November, when the weather was chilly and sunlight scarce, and as Gehl argues, successful outdoor public spaces should show seasonal fluctuations in use because this indicates that in good weather, places becomes more attractive.17

All the seating areas in the study were used by non-sitters to varying degrees. In the indoor spaces, non-sitters used seating areas to collect V&A leaflets, rest their bag on a seat, or to put on (or take off) jackets and hats. The outdoor space, the Grand Entrance Steps, supported particularly varied use among non-sitters and, as expected, were the only space in the study where smoking was observed. The Grand Entrance Steps were the most playful and informal of all spaces. One activity observed for non-sitters in this area was people walking up or down the rounded edges of the steps in a ‘stepping-stone’ fashion – both children and adults. One person even did a small dance. The Grand Entrance Steps were the only space in the study used by non-visitors to the V&A, which supports the observations about the steps to civic buildings made by Paul Goldberger (1987).

In contrast, the Sackler Centre was the least used by Non-sitters, who used the space mainly as a thoroughfare. As the Sackler Centre appeared to be used by visitors during the course of their visit, there was less evidence of using the seating area to put on or take off clothing. Though leaflets are provided in the Sackler Centre, they are not as often collected by visitors passing through as in the Grand Entrance. The seating in the Sackler Centre was apparently still attractive to Non-sitters, evidenced by people touching the seats as they walked past, and a child who broke away from his school group while they were passing through the space to sit briefly in an hm85a chair.

Conclusion

Perhaps the most remarkable and counter-intuitive outcome of this research was that ‘comfort’ played little part in the kinds of use observed. The area with the most comfortable seating, the Sackler Centre, had the lowest average sitting time in the study (3 minutes 89 seconds) compared with 17 minutes 27 seconds on the Grand Entrance Steps – arguably the area which places the highest demand on the sitter in terms of comfort. There was little difference between the sitting times in the interior spaces, though these spaces offer contrasting seating in the form of hard benches and soft couches. The slightly longer sitting times observed in the busier spaces suggests that interest (something to watch) is perhaps more of an invitation for visitors to linger in the space than comfort, though this is difficult to confirm with observational data.

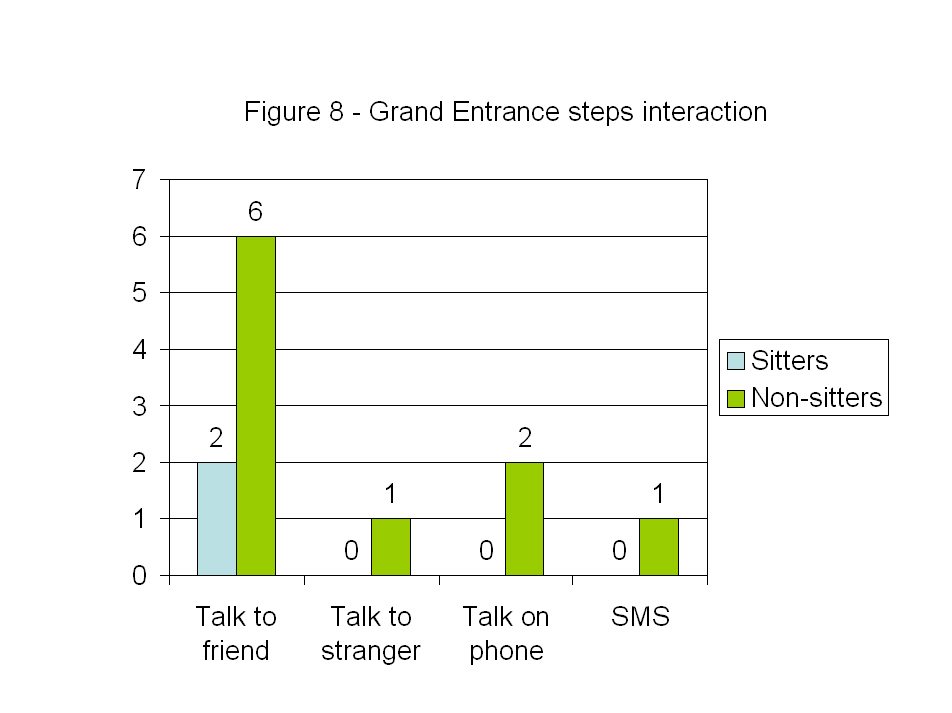

Figures 7–9 below illustrate the kinds of interaction observed in each space in the study.

All seating areas displayed evidence of ‘congregant’ behaviour and people-watching. The space which had the most evidence of sitting and circulation, the Grand Entrance, had the most evidence of interaction for both Sitters and Non-Sitters. In all spaces, interaction tended to occur between friends, though interaction between strangers was also observed in all spaces - always for a purpose specific to the space: joining a guided tour (Grand Entrance), procuring a cigarette (Grand Entrance Steps), or taking part in a questionnaire (Sackler Centre). The Grand Entrance Steps had the most evidence of interaction between Non-sitters, in contrast to the Sackler Centre, where there was no evidence of interaction for Non-sitters. On the other hand, the Sackler Centre did have the most evidence of interaction between friends.

The Sackler Centre was also the only space where meetings were observed, making use of the moveable and swivel qualities of the seating unique to this area. On both occasions, the hm85a chairs were oriented to face other members of the group, and an MT1 chair was moved from its usual position. Interestingly, on the conclusion of each meeting the participants left the chairs in this new configuration. There is much written about the benefits of moveable seating in public spaces, because it allows people to create the most suitable arrangement for their particular purpose.18 In New York, moveable seating has been provided in public parks for many years (with a surprisingly low theft rate). Whyte praises the moveable seat for its ability ‘to move into the sun, out of it: to move closer to someone, further away from another’.19 The sociability offered by moveable seats appears to be attractive to visitors and this study showed that where seats can be moved, they will be moved.

The study was limited both by the observational methodology and by the short duration period for data collection in just one season. This means that it could not reliably evaluate qualitative aspects of sitting such as comfort, or whether Non-sitters did not sit down because of lack of available seating space or for other reasons.

The study did however confirm Gehl’s observations that seating, as an invitation for people to linger, is a starting point for the range of activities that can happen in public spaces, such as reading, meeting people, eating, smoking, talking, or people-watching. Although evidence of exclusion was not part of the remit of the study, it is worth noting that all three locations appeared to be inclusive spaces that were self-managing. The study found differences in the activities displayed by Sitters and Non-sitters in the three areas observed, as well as contrasts between the indoor and outdoor seating areas in the study. The interior spaces appeared to be more formal than the outdoor space, which supported the most playful activities.

The study confirmed Whyte’s findings about the complementary nature of seating and circulation – the best example of which was the Grand Entrance, which tended to encourage lingering amongst Sitters and Non-sitters, as well as a slightly longer stay for Sitters, more than the quieter space (Sackler Centre). This finding suggests that for circulation areas, busier means more varied activity and thus, perhaps, a more attractive space for staying, though again this is difficult to confirm with only observational data.

One surprising finding from the study was that very few people appeared to use the seating areas to go online – only one person was observed using a laptop during the course of the study, out of a total of 54 Sitters observed. An area for future consideration in the V&A could be to display the wifi symbol in seating areas to encourage more visitors to make use of the free internet access provided by the Museum. The study also found that while reading was prevalent among Sitters, people overwhelmingly read V&A leaflets. In the Sackler Centre, where reading V&A leaflets was not as commonly observed as in the Grand Entrance, the provision of more varied print material such as newspapers or sample copies of V&A books could encourage visitors to spend more time in the space.

Though more research is needed to evaluate qualitative aspects of the seating provided by the Museum (such as where visitors feel most welcome, the importance of factors such as comfort, and visitor motivations for lingering in circulation spaces), the study gives an insight into the multiple ways visitors use seating areas and highlights seating as an important provision for visitors - not only as places to rest and wait, but as an invitation to participate in the public life of the Museum.

Endnotes

-

Sucher, David. City Comforts. Seattle: City Comforts Inc., 2003: 26. ↩︎

-

Heumann Gurian, Elaine. Civilizing the Museum: the collected writings of Elaine Heumann Gurian. New York: Routledge, 2006: 108. ↩︎

-

Heumann Gurian, Elaine. Civilizing the Museum: the collected writings of Elaine Heumann Gurian. New York: Routledge, 2006: 100. ↩︎

-

Jacobs (1961) quoted in Gurian, Civilizing the Museum, 100. ↩︎

-

Gehl, Jan. Life Between Buildings. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1987: 157. ↩︎

-

Gehl, Jan. Life Between Buildings. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1987: 23. ↩︎

-

Heumann Gurian, Elaine. Civilizing the Museum: the collected writings of Elaine Heumann Gurian. New York: Routledge, 2006. ↩︎

-

Jacobs (1961) quoted in Heumann Gurian, Elaine. Civilizing the Museum: the collected writings of Elaine Heumann Gurian. New York: Routledge, 2006. 108. ↩︎

-

Whyte, William. City: Rediscovering the Center. New York; London: Doubleday, 1988: 110. ↩︎

-

Goldberger, Paul. ‘New York City Out-Of-Doors; Cavorting on the Great Urban Staircases’. New York Times. 7 August, 1987. ↩︎

-

Gehl Architects, ‘Towards a Fine City for People’, 2004: 49 (accessed January 2011) ↩︎

-

Whyte, William. City: Rediscovering the Center. New York; London: Doubleday, 1988: 116. ↩︎

-

V&A Website, ‘Futureplan Completed Projects’ (accessed January 2011) ↩︎

-

Eva Jirinca Architects Website, ‘Projects, Public Buildings’. ↩︎

-

The incline is technically termed a ‘slope’, as distinct from a ‘ramp’, which would require ironmongery and edge detailing. ↩︎

-

Penny Richards (6 April 2010), personal correspondence. ↩︎

-

Gehl, Jan. Life Between Buildings. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1987: 75–81. ↩︎

-

See Project for Public Spaces, https://www.pps.org/articles/seating/ (accessed January 2011) ↩︎

-

Whyte, William. City: Rediscovering the Center. New York; London: Doubleday, 1988: 119. ↩︎