Abstract

During preparations for Quilts 1700–2010 (20 March - 4 July 2010), many of the Museum’s quilts were taken out of store for the first time in decades so that they could be photographed and examined prior to conservation. Following the publication of X-radiography of Textiles, Dress and Related Objects in 2007, many textiles have been X-rayed to gain information about them. Quilts in particular have been singled out for analysis because of their multi-layered construction. This article discusses three 18th- and 19th-century quilts in the V&A’s collections, whose histories of making were revealed through X-radiography, as much as the materials they were made of.

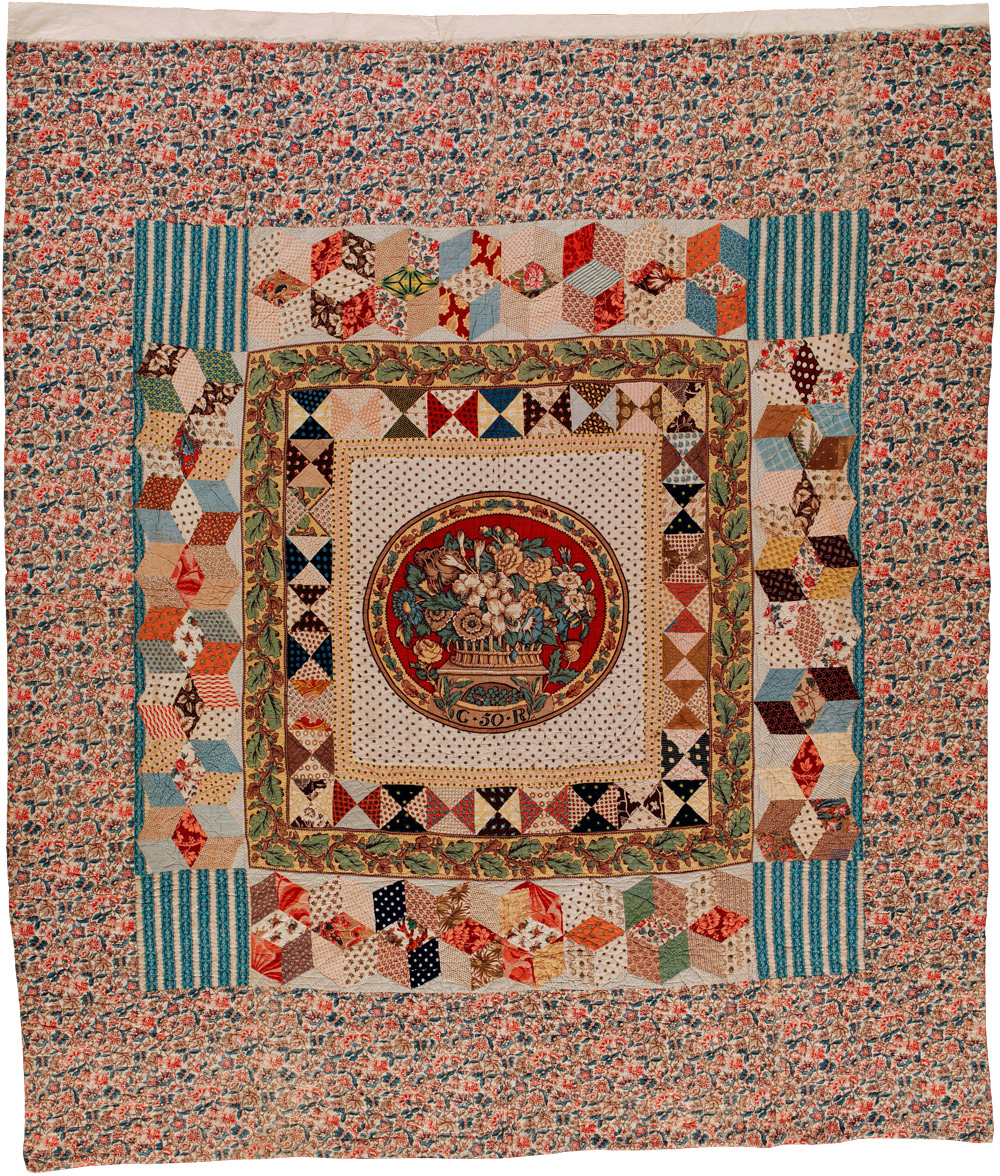

The examinations that form the basis of this article were prompted by the observation that a quilt to be featured in the exhibition Quilts 1700–2010, made from fabric printed for the celebration of King George III Golden Jubilee (fig. 1), had a different quilting pattern on the back of the quilt than that on the front. Close inspection of the edge of the quilt revealed four layers of textile - the present top, a previous quilt top, a mysterious secondary textile, and the original lining.

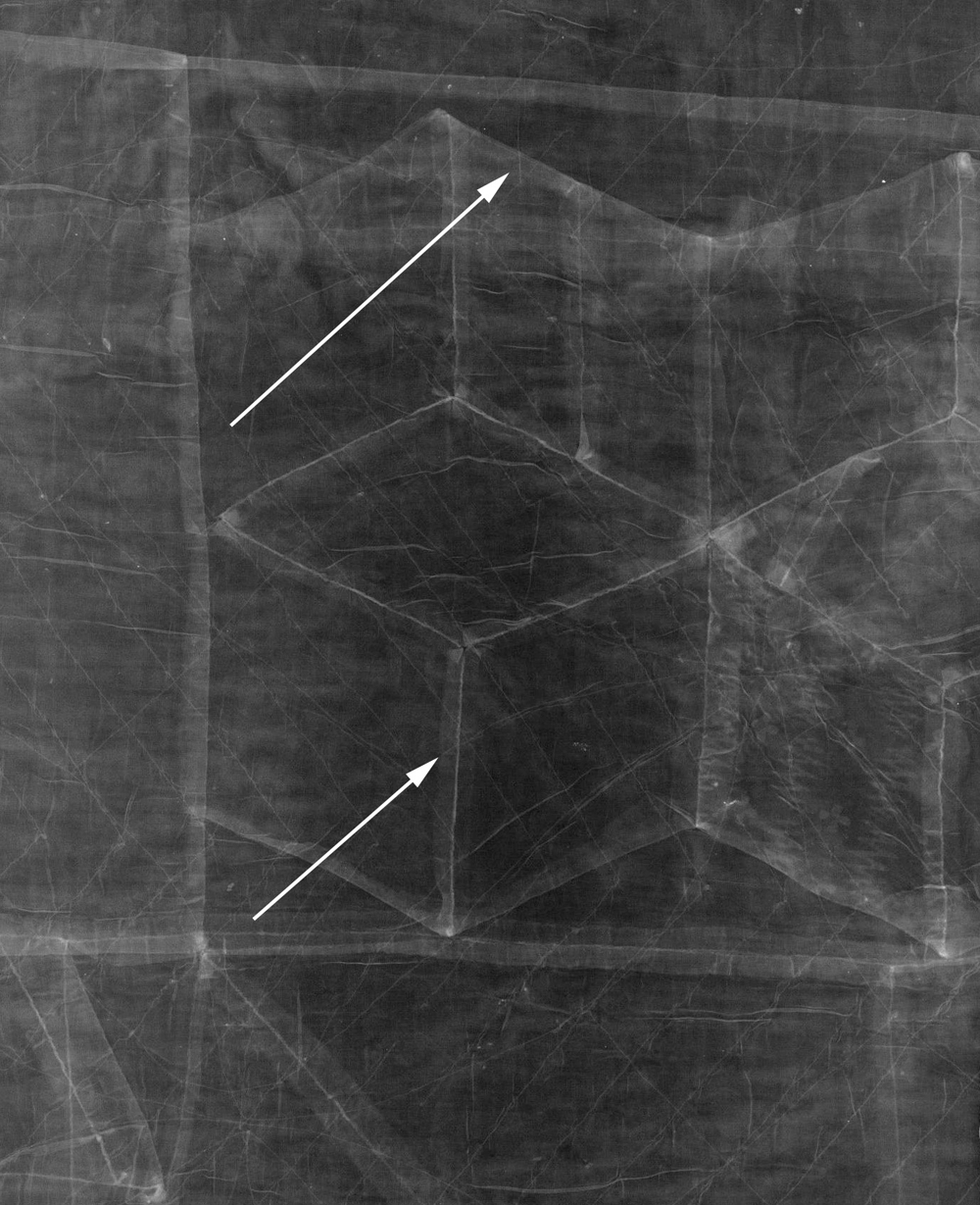

It is generally understood that a quilt is defined as two layers of fabric, sometimes with a layer of padding between, all sewn together so that the sewing threads pass through all layers. The sewing used to bind the layers together often forms decorative patterns. An X-ray is a picture of relative material density, with denser materials appearing white and voids or breaks appearing dark. Folded areas of fabric are denser and appear lighter on an X-ray. Patchwork is made from an arrangement of fabric pieces and the way that the fabric is sewn together is known as piecing. The technique of piecing over paper, which is found in many British quilts, involves folding fabric around a paper template, basting it in place with long stitches, and then joining the basted pieces together edge-to-edge with tiny whip-stitches. The basting stitches are then removed and the paper is either removed or retained inside the quilt for stiffness and warmth. Using an X-ray image it is possible to see that the individual tumbling block pieces in the inner border of the quilt are pieced over paper – with the seam allowance on either side of the seam, while the tumbling block section as a whole has been applied to the quilt top as a strip with the seam allowance folded to one side (fig. 2).2

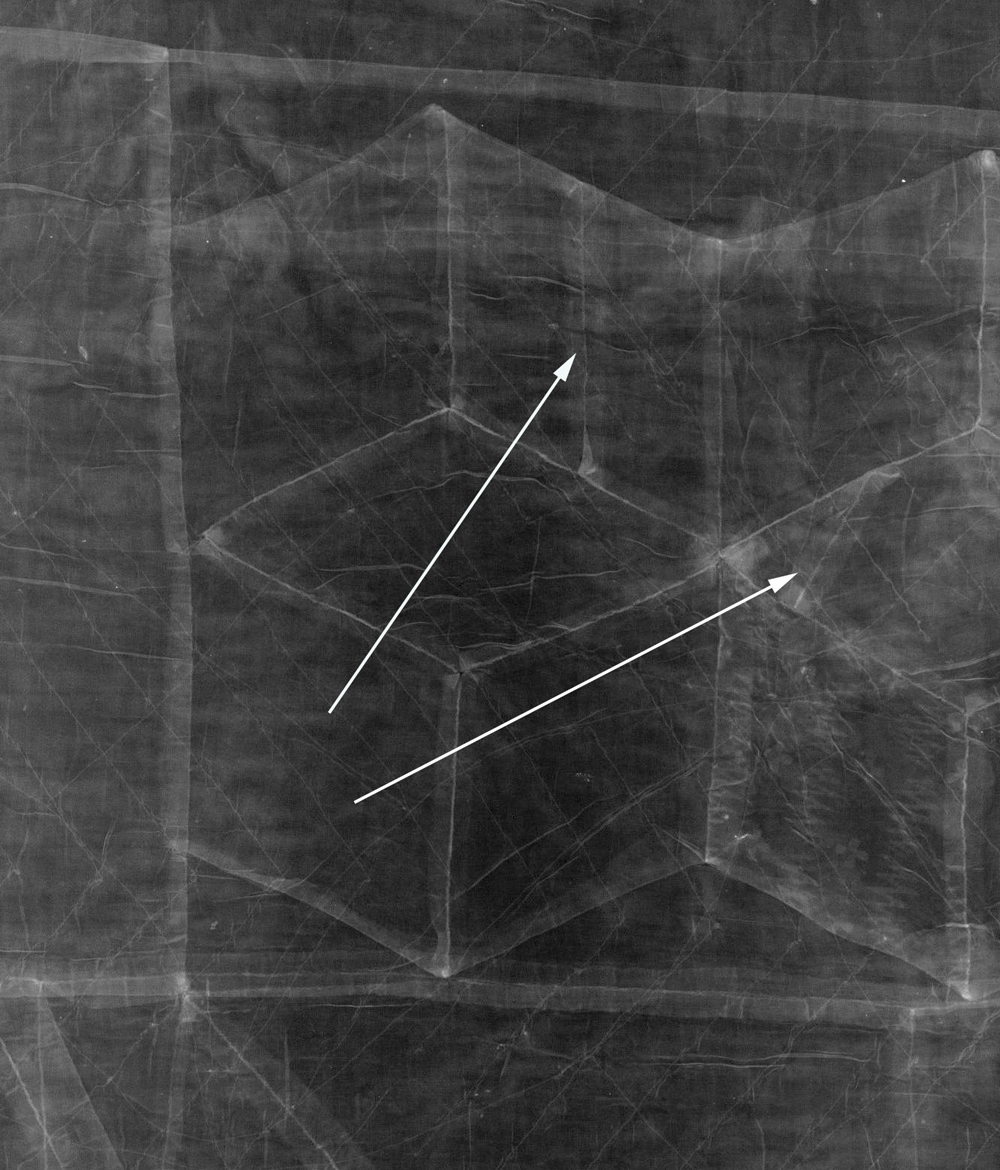

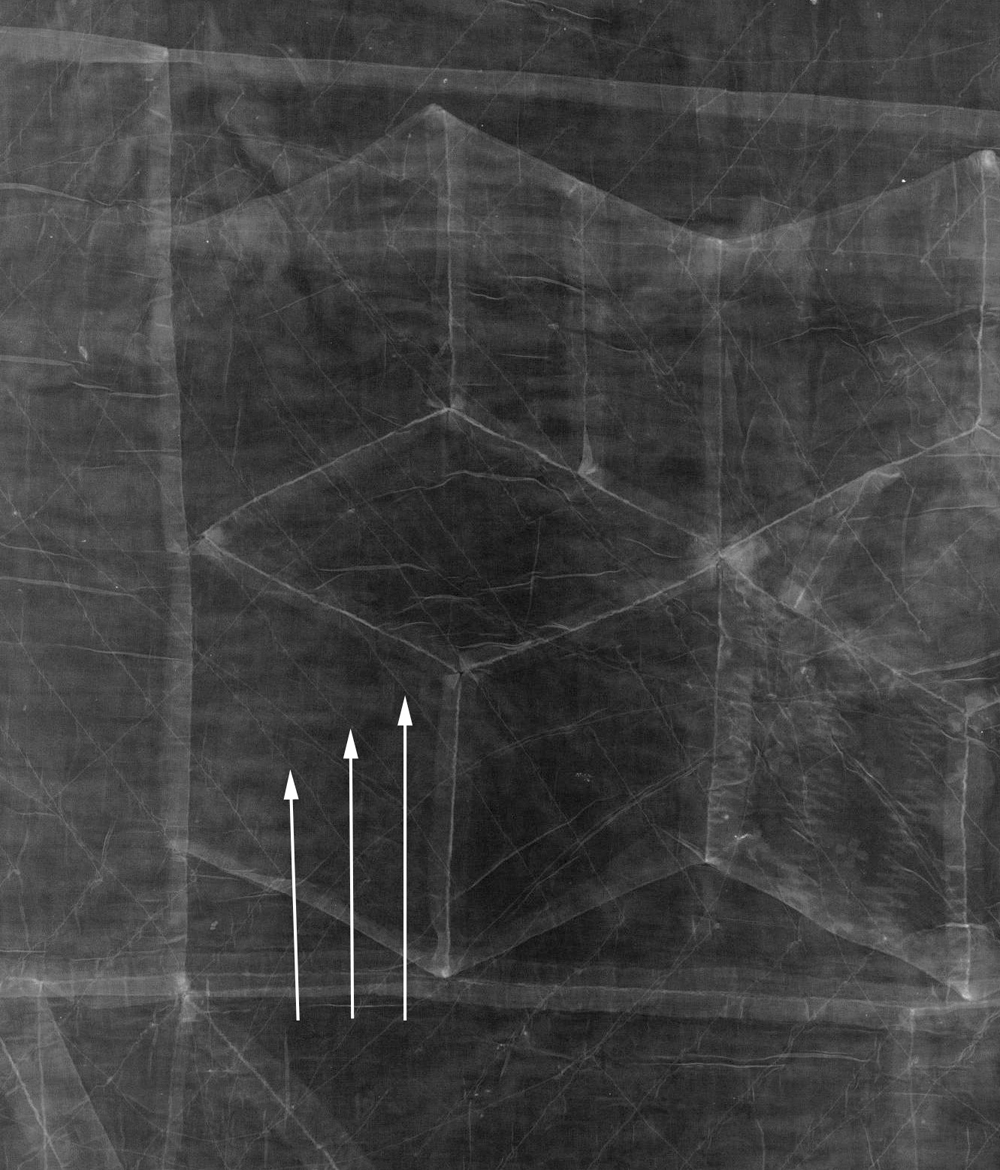

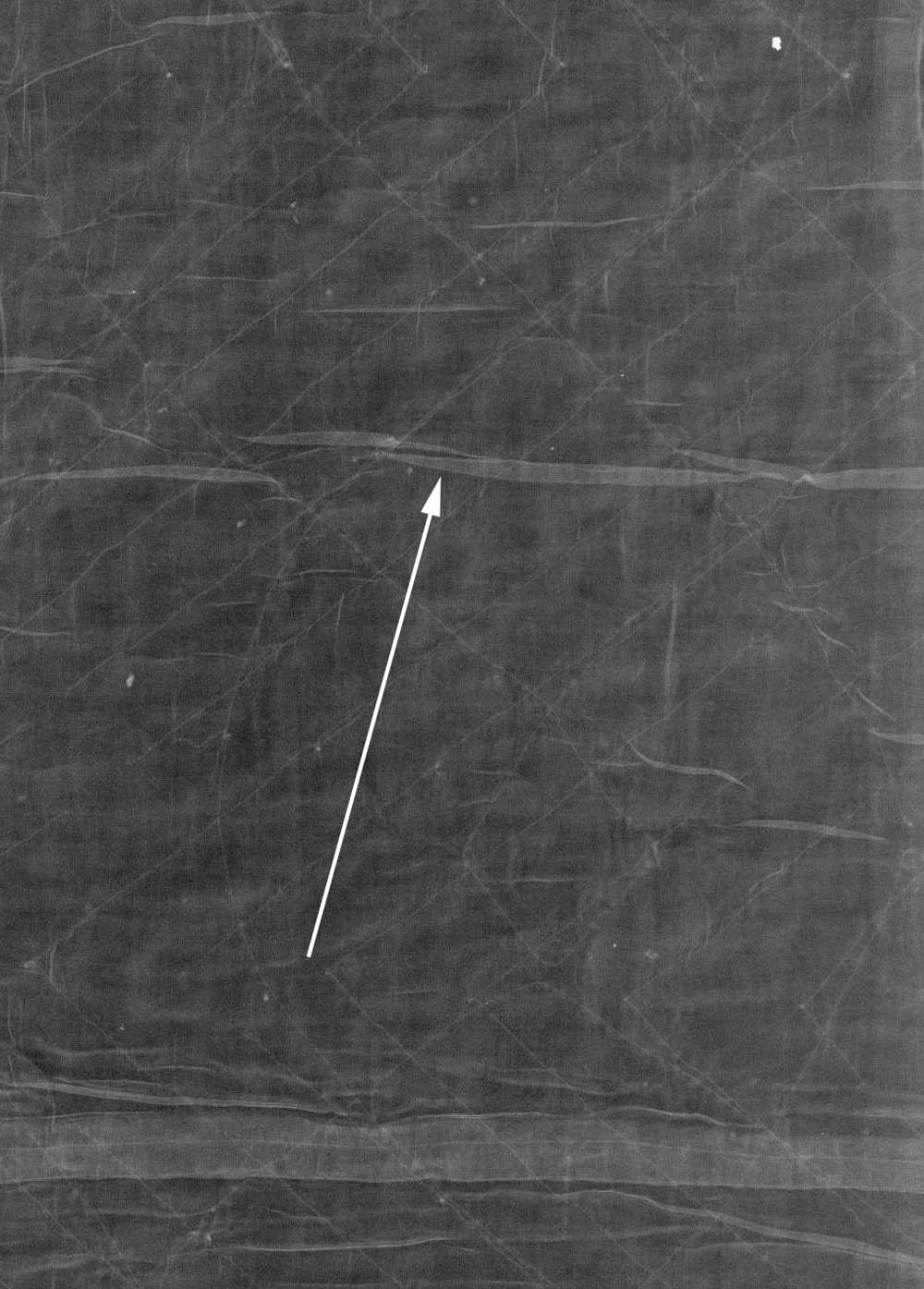

This seemed to be a useful tool to employ in the examination of the George III Jubilee quilt (fig. 1). Obvious construction details such as seams within the fabric of individual pieces and quilting threads are clear to see, however, with X-ray investigation, much more subtle details such as wrinkles in the previous quilt top and different density of dyes in prints can also be seen (figs 3–6).

The bed cover, made in around 1810, features a commemorative central panel surrounded by printed cottons dating from the early 19th century. The front is quilted with a pattern of interlocking circles, whilst the reverse is quilted in a chevron pattern, indicating that this bedcover had a previous top, perhaps hidden below the quilt top which we see now. Glimpses of underlying fabrics were exposed through small holes in the top and lining (figs 7–8). Purple and white striped cotton could be seen though holes in the border and a brown and cream printed fabric could be viewed through a hole in the lining in the centre back of the bedcover

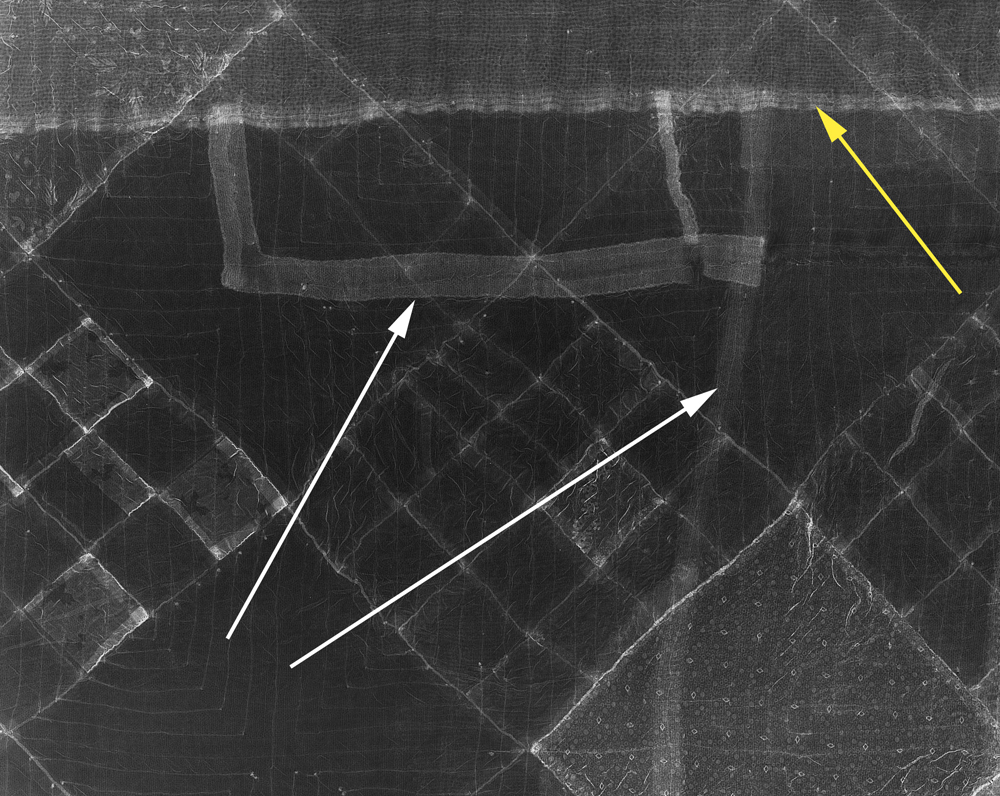

The key to understanding the original top of the George III Jubilee quilt was found in an X-ray showing several intersecting long seams in the border of the quilt (fig. 9). Taking into account seams visible on the present top and lining, any additional seams appearing in the X-ray belong to the previous top.

By taking further X-ray images along one edge of the quilt and several from one edge into the centre, it became clear that the previous quilt had a plain centre surrounded by two concentric borders. There was no central medallion on the older quilt top and the bedcover was simply quilted all over in a chevron pattern. X-ray images of the centre of the quilt indicated considerable wear and damage to the fabric and glimpses of the older quilt top seen through holes in the face of the quilt confirmed that the fabric was weak cotton with tendering brown printed areas.

Having enriched our understanding of the George III Jubilee quilt using X-Ray images other quilts were examined for evidence of re-used materials. A patchwork and quilted bedcover dating from the early 19th century was examined next (fig. 10).

This quilt, made over a long period of time, contains over 3,000 patches. The central medallion, commemorating the Battle of Victoria in 1813, is pieced beside printed cottons from the 1830s.

The quilt contains a large variety of prints with subtle variation on a single design, this and the presence of a printer’s stamp on one piece suggest that the maker bought fabric directly from the factory or from peddlers selling printer’s ends specifically for quilt making (fig. 11).

The quilt is wadded with woollen materials that could be seen through a tear in the lining of the quilt and at one corner where the lining was loose (fig. 12).

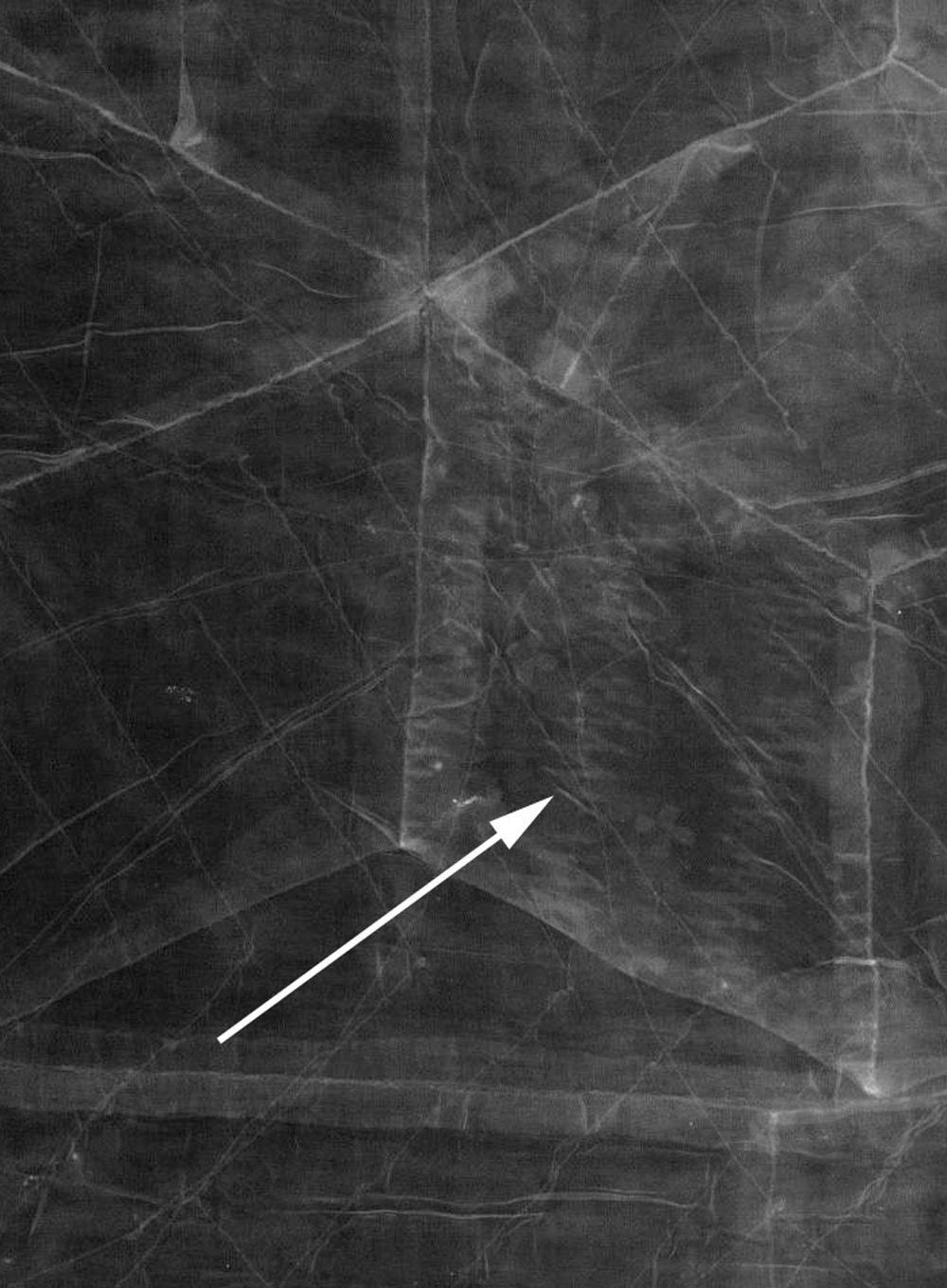

Clearly defined ridges in the wadding could be felt approximately 30 cm from the bottom edge of the quilt. X-rays taken along the edge of the quilt revealed that an entire woollen blanket with rolled hems at top and bottom and a butt-joined seam down the centre had been used as the main part of the quilt wadding. As the blanket was smaller than the finished quilt, pieces of other woollen materials had been seamed together to fill in the gaps around the edge (fig. 13).

An X-ray of the very edge of the quilt illustrates that this pieced addition to the blanket had not been quite big enough and a further narrow border of strips of woollen material 3 cm wide had been added to the edge.

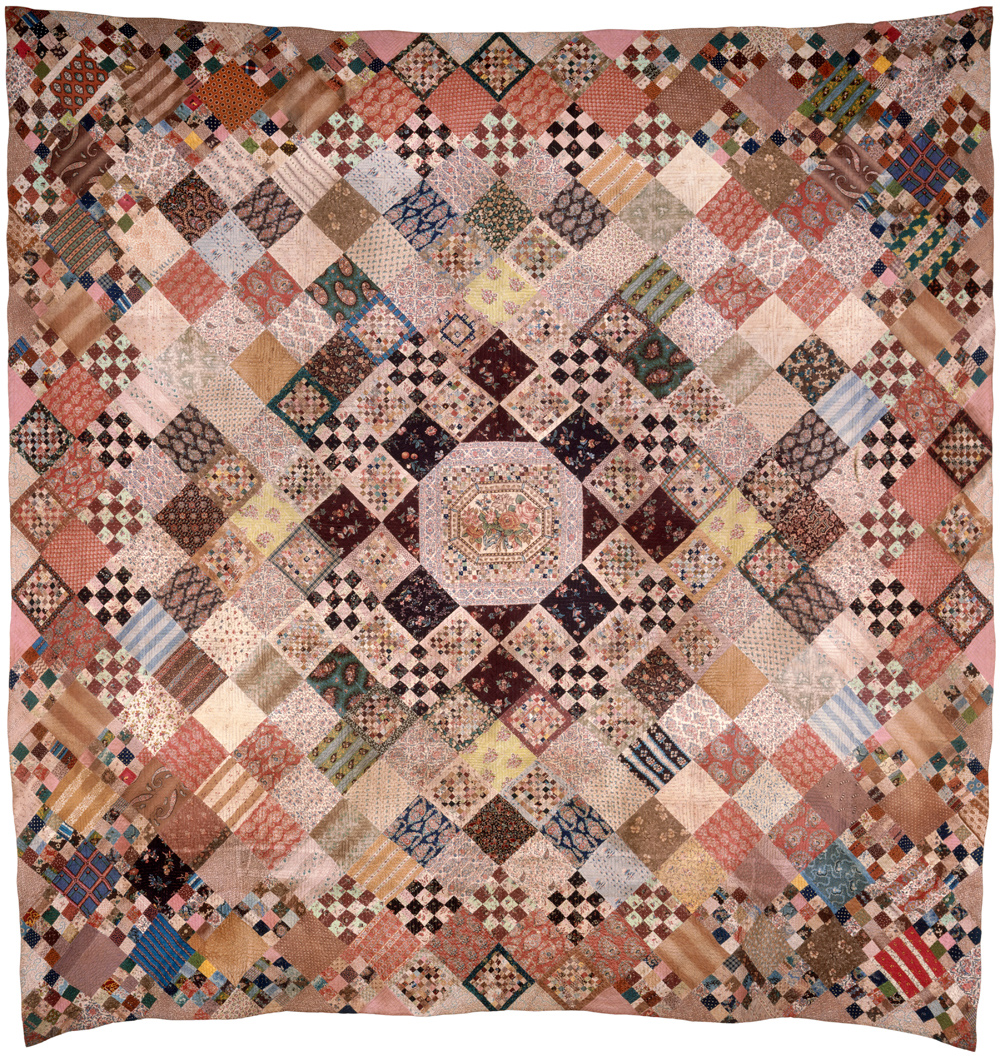

Lastly, a magnificent, coverlet dated 1797, was examined and X-rayed. This coverlet, known as the Sundial Coverlet, is one of the better known bedcovers in the V&A’s collection (fig. 14).

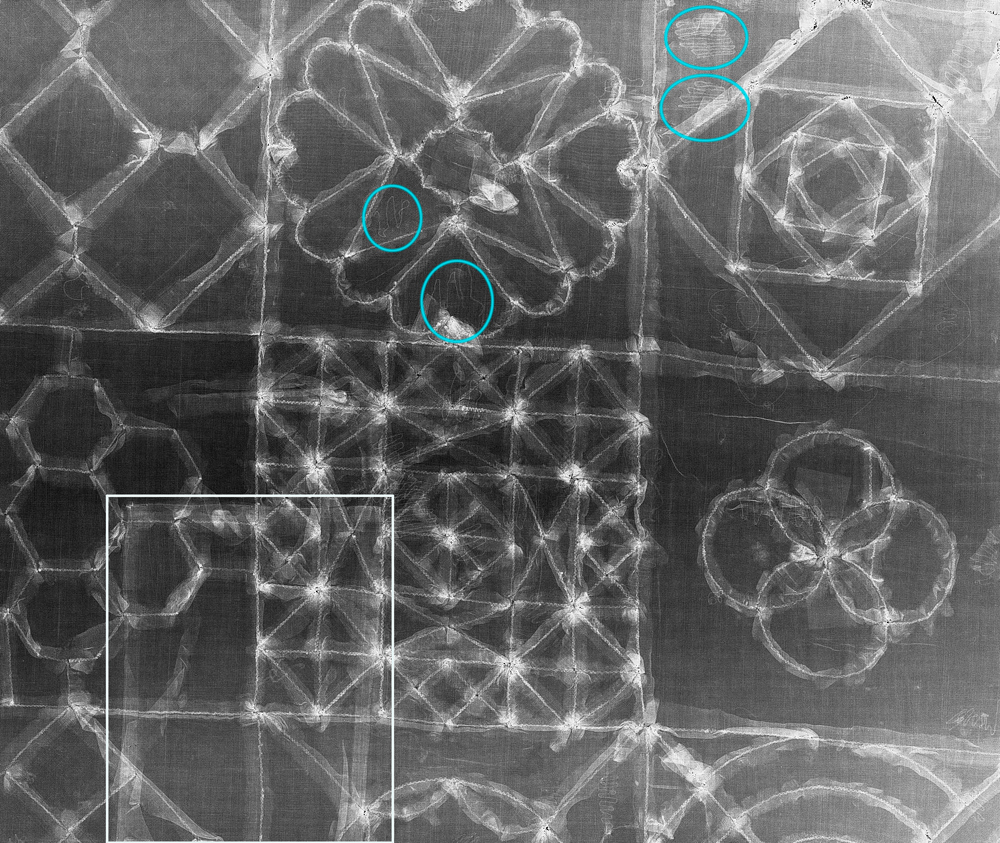

There are such a wide variety of printed dress cottons in the quilt, all with a predominately pink, brown and blue palette, that it has been speculated that the maker was in some way connected to the textile trade, either through cotton manufacture or via a linen merchant, or, that the fabric was specifically bought from dress makers for making patchwork.3 The maker appears to have been an educated person of taste and with advanced needle skills. The complexity of the piecing is extraordinary, even the detailed maps of Britain and the world are pieced over paper, which suggests a maker with ample leisure time as this type of construction is extremely slow (fig. 15).

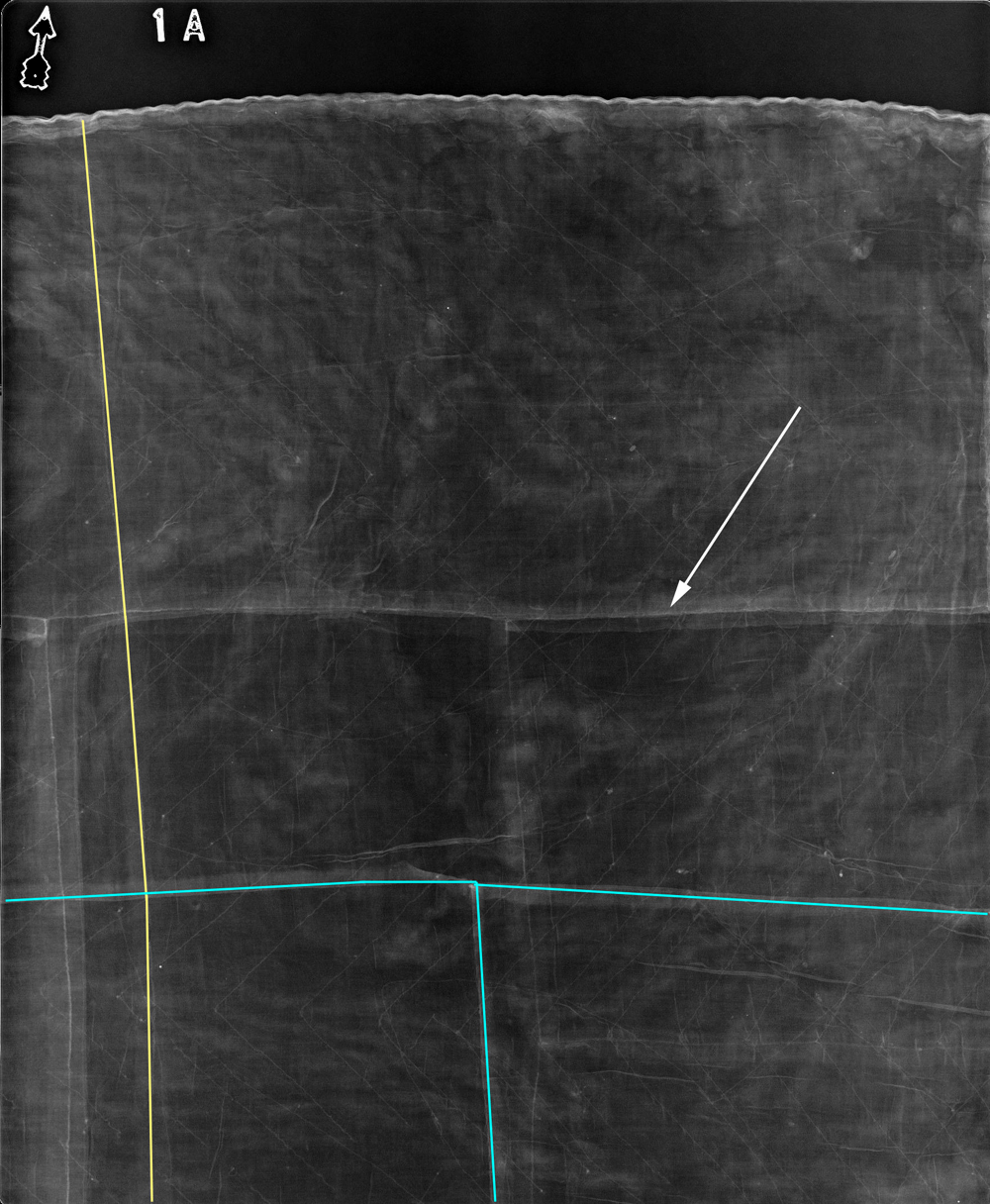

On examining the reverse of the coverlet it was determined that the lining had been made up from many pieces of worn cotton and that the back was covered with dozens of areas of darning. X-ray examination confirmed that the darning, including some very large and neatly done patches not visible on the surface of the coverlet, was not related to damage on the face of the coverlet (figs 16–18).

The person who had applied the lining to the coverlet had not even taken the time to remove the scraps of previous textile trapped by the darning. They had simply cut around them and left the remnants in place (fig. 18). This seemed inconsistent with the effort made with the front of the coverlet.

These quilts were made by women in different circumstances and over varying periods of time, but each quilt required many hours of labour and considerable investment in materials, so one might question why such poor quality and worn out materials had been used to line and wad their needlework? While some quilts could be classified as having been made with scrap materials out of economic necessity and other quilts might simply have been made hastily from whatever was conveniently at hand, the use of shoddy materials in quilts such as the Sundial coverlet must have involved some other motivating factor.

The Battle of Victoria Quilt perhaps best conforms to our idealised version of an historic quilt. Something made from discarded scraps and bits and pieces of fabric over a very long period of time. The wadding is made of pieced sections of blanket out of necessity. The use of blankets as wadding is a feature of quilts made in rural areas, especially Wales, where wool is abundant and blankets are locally made.4 The maker wanted a warm quilt and worn out blankets were readily available and had little value. The recycling of an entire quilt to form the wadding and lining of the George III Jubilee quilt suggests an opportunistic use of a material. It is likely that the new quilt top was swiftly made to set off the commemorative panel and to extend the life of a worn-out and perhaps unfashionable item of household linen. The piecing is not complex and in some areas is directly applied to the original quilt below.

It is the Sundial coverlet that poses the most questions. The maker appears to have been affluent with abundant leisure time and clearly had access to the materials necessary to make a splendid work of art, yet recycled materials are used for the lining. Plain cotton calico was a relatively cheap commodity in 1797 but the lining on this coverlet, which would have been seen by visitors to the maker’s home, is shabby. Perhaps the maker was making a point about the morality of thriftiness to compensate for the display of conspicuous consumption evidenced on the front of the coverlet? The Workwoman’s Guide, a practical handbook to making household linens published in the 1830s, certainly thought that the thrifty disposition was a moral one and should be diligently cultivated.5 Alternatively the coverlet may simply be an example of the aesthetic values of the day.

Late 18th-century case furniture may be highly ornamented and polished on the face but completely unfinished on the reverse with marks from the plane and chisels clearly visible.6 This may be a textile example of this lack of finish on unseen surfaces. Another possibility is that someone else may have both supplied and applied the lining. In the late 18th century, a good deal of the time of both the mistress and the housemaids of a genteel family would have been devoted to the making and mending of household linen such as shirts, shifts and sheets.7 It seems likely that once the aesthetically rewarding work of planning, piecing and embroidering the coverlet top was finished, the work was passed to a domestic servant to line with plain calico. Having no emotional investment in the item, the servant simply did not bother to remove the old repairs from the lining fabric before it was applied and we must assume that the maker either did not see, or mind, the striking contrast in handiwork presented by the finished quilt.

Endnotes

-

Mary M. Brooks, Sonia O’Connor and Josie Sheppard. ‘X-Radiography of patchwork and quilts’ in X-Radiography of Textiles, Dress and Related Objects, Sonia O’Connor and Mary M. Brooks. Elsevier, 2007. See also Tina Fenwick Smith and Dorothy Osler. ‘The 1718 silk patchwork coverlet: Introduction in Quilt Studies’ in The Journal of the British Quilt Study Group. 4/5 (2002/3). ↩︎

-

All X-radiography done by Paul Robins, photographer and radiation protection supervisor at the V&A. X-radiography done at 30 KV for 12 seconds FFD of 75 cm. ↩︎

-

Prichard, Sue (ed.). Quilts 1700–2010. V&A Publishing, 2010: 176. See also Barber, J. ‘Fabric as Evidence: Unravelling the Meaning of a Late Eighteenth Century Coverlet in Quilt Studies’ in The Journal of the British Quilt Study Group. 3 (2001): 17. ↩︎

-

Jones, Jen. Welsh Quilts. Towey Publishing, 1997: 11. ↩︎

-

Lady, A. The Workwoman’s Guide. (Second Edition). Birmingham: Thomas Evans, 1840: v. ↩︎

-

For example, the commode made by William Vile for Prime Minister George Grenville between 1762 and 1764. (V&A W.32-1977). The commode, made from highly finished mahogany with gilded brass mounts and doors with silk panels set behind gilded brass grills, has a completely unfinished back on which marks from hand planes can be clearly seen. ↩︎

-

Vickery, Amanda. The Gentleman’s Daughter: Women’s Lives in Georgian England. Yale University Press, 2003: 150–151. ↩︎