Abstract

The Victoria and Albert Museum has been collecting computer art since the 1960s. In recent times, it has acquired two significant collections of computer-generated art and design, which form the basis of the UK’s national collection. This article considers the collection within the context of the V&A, as well as its wider cultural and ideological context.

The arrival of the computer into both the creative process and the creative industries is perhaps one of the most culturally significant developments of the last century. Yet until recently, few, if any, UK museums have collected material that comprehensively illustrates and charts this change. The donation of two substantial collections of computer-generated art and design to the Word and Image Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum offers the opportunity to redress this. The donations have considerably strengthened our holdings in this area and the museum is now home to the national collection of computer-generated art and design. These acquisitions will allow the museum to re-assess the impact of the computer’s arrival and to attempt to position these works within an art historical context for the first time.

The importance of such an endeavour has been recognised by the awarding of a substantial Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) grant to the V&A and Birkbeck College, University of London. Since 2007, research has focused on investigating the origins of computer-generated art from the 1950s, and its development through subsequent decades. As well as full documentation and cataloguing of the collections, the V&A is organising a temporary display entitled Digital Pioneers, opening in December 2009, which will draw almost entirely from the newly acquired collections and recent acquisitions. This will coincide with a larger V&A exhibition, Decode: Digital Design Sensations, which will include important international loans of contemporary digital art and design, alongside new commissions.1 Digital Pioneers will present a historical counterpart to the contemporary exhibition, encouraging comparisons that, until now, have been drawn far less frequently. A conference covering the subject matter of both exhibitions will take place in early spring 2010 and will create an academic forum in which these comparisons can be examined more fully. We hope it will also allow for an opportunity to further the process of documenting and recording the history of this field.

The intention of this article is to give a broad introduction to the area of computer-generated art and design within the V&A, as well as considering its wider art historical context, both in Britain and abroad. Intended as a starting point for those who find themselves interested in the topic, more information is available on the V&A website.

The Word and Image Department and the new computer art collections

The Word and Image Department of the V&A encompasses prints, drawings, paintings, photographs, designs and the National Art Library. It holds approximately two million objects ranging from the Middle Ages to the present day. The V&A has always relied on the generosity of donations to continue to expand and strengthen its holdings. The new acquisitions from the Computer Arts Society, London, and American art historian and collector, Patric Prince, provide an extraordinarily broad range of computer-generated art and design that complements many other areas of collecting within the department, such as graphic design.2 The Department was particularly well placed to accept this material, embracing in its collecting policy those works or creative endeavours that fall between fine art and design, such as early computer-generated work, including animation and graphics. The Department also places significant emphasis on process and technique alongside the finished product, actively collecting objects such as printing tools and equipment, for example, as well as documentary material that demonstrates work in progress.

At present, the V&A’s computer art collections consist predominately of works on paper, including early plotter drawings by important pioneers such as Manfred Mohr, and examples of early animation stills and negatives. Holdings range from screenprints, lithographs and photographs of early analogue computer-generated images from the mid 1950s, to digital images from the 1960s onwards. Together, the two founding collections contain around 350 art works. In addition, the V&A has made significant acquisitions since the beginning of the research project, which include works by key computer art pioneers such as Paul Brown, Harold Cohen, James Faure Walker, Desmond Paul Henry, Roman Verostko and Mark Wilson.3

The Patric Prince collection was accompanied by a substantial archive of material charting the development of computer-generated art. Prince’s husband, Robert Holzman, worked at the NASA Jet Propulsion Lab in America and encouraged artists to use the Lab’s powerful equipment out of hours. As a result, she had access to early practitioners as and when they were experimenting with this equipment for the first time. Gaining a reputation as an important curator and collector of computer art, artists corresponded regularly with Prince and the archive includes this correspondence, as well as exhibition cards and literature for computer related exhibitions in the US, and to a lesser extent elsewhere, from the 1980s onwards. Press cuttings from mainstream newspapers provide illuminating evidence about prevailing attitudes to the use of computers in art during this time. A substantial library of books now listed on the National Art Library’s catalogue offers a virtually unparalleled reading list for this field, and includes important early and rare texts.4

Defining computer art

The arrival of a complex field of art and design into a national museum has intensified a need to further define and record the history of this area. Computer art’s development across the fields of mathematics, engineering, computer science and industry, as well as the fine and applied arts, means that its history is a shared one, with the term ‘computer art’ meaning different things to different people at different times. Within the context of the V&A’s collection, computer art can be understood as a historical term that relates to artists using the computer as a tool or a medium from around the 1960s until the early 1980s. At this point, the appearance of off-the-shelf software and the widespread adoption of personal computers meant that more people were able to use the computer as a graphical tool without needing a background in programming. Simultaneously, the nature of computer-generated art changed irretrievably. As the sector widened, more artists began to work with digital technologies in increasingly open and interchangeable ways. The intense focus of early practitioners on basic hardware and the very building blocks of the computer - something which stills drives them today, even in the face of more sophisticated technology - is particular to that first generation of computer artists.

Early beginnings

Some of the earliest practitioners were scientists and mathematicians, since mainframe computers could only be found in large industrial or university laboratories. Equally, a scientific or mathematical training offered the expertise necessary toprogramme the cumbersome and complicated early computers that offered no visual interface - something that would have been virtually impossible for the ‘lay person’. The involvement of scientists and mathematicians, some of whom went on to adopt the role of ‘artist’, is one reason why many in the mainstream art world had difficulty in accepting computer-generated art, both at the time and for years to come. Until recently it was extremely rare to find any mention of computer-generated art in accounts of modern and contemporary art history from the 1960s onwards. Yet an analysis of this type of work reveals many similarities with other better known movements of the same era, some of which are touched on below.5

Conversely, at the time of its production, computer art was widely written about and documented - more so, in fact, than other movements from a similar period, such as Conceptual Art.6 Early computer art shared its origins with scientific visualisation techniques and much of its development continued to be charted through science or mathematics journals, with the imagery produced being regarded as merely a by-product of the more serious scientific pursuits. This situation, and computer art’s inextricable relationship with the technology on which it relied, has meant that until recently, most texts on computer art have tended to be structured around a techno-centric narrative. Other technology-focused art forms that emerged alongside computer art, such as kinetic art and video art, have fared better and kept their place in the history books. The constantly changing technology on which computer art relied, and the speed at which it developed, meant that recording it was difficult and accounts were frequently out of date. Computer art did find fame, however, in the more mainstream press of its day. The mechanical drawings of Desmond Paul Henry, of which the V&A hold three early examples, were created using an analogue bombsight computer adapted by the artist into a drawing machine. They were reported in The Guardian, the BBC’s North at Six series, and, had it not been for the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Time Magazine. The Guardian article of 1962 described Henry’s images as, ‘quite out of this world’ and, ‘almost impossible to produce by human hands’.7 The sensationalist tone sets it apart from more scholarly art criticism and suggests the novelty of this new type of art, as well as a sense of the utopianism surrounding the new technology that was still felt by many at this time.8

Influences and interests

The influences on early computer artists are varied, but the increasing interest in and application of cybernetic theories, which followed heavy military investment in computing during World War II, encouraged a new way of thinking and working that permeated the arts as well as other elements of culture and society. C. P. Snow’s influential Cambridge Rede lecture of 1959, The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution,9 in which he argued for the uniting of the humanities and the natural sciences, did much to foster a supportive atmosphere for such work.10 The application of cybernetic theories in the field of aesthetics was developed by a number of theorists working at this time, amongst them Max Bense. Bense’s influence has been acknowledged by several early pioneers in the field of computer art and design, most particularly, within the context of the V&A’s collection, the Germany-based practitioners Frieder Nake and Georg Nees.11

Max Bense and information aesthetics

Between the years 1954 and 1965, Bense developed his theories of information aesthetics, through which he attempted to establish a scientific model for creating, or understanding, successful aesthetics. Bense argued for an objective, rational approach that included ‘breaking down’ images into their mathematical values and using theories examining the relationship between order and chaos in the composition. Bense was a key figure of the Stuttgart school, an intellectual movement that incorporated theories of information aesthetics into its thinking. He was also professor of the philosophy of technology, scientific theory, and mathematical logic at the Technical University of Stuttgart, from 1949 to 1976. Computer art pioneer Frieder Nake was studying mathematics at the Technical University during this time and has acknowledged the influence of Bense’s lectures. From 1961 to 1964, Nake worked as an assistant in the University’s computer centre. Whilst there, he wrote software that enabled him to use the centre’s ZUSE Z64 ‘Graphomat’ - an early computer-driven drawing machine - as an output device for the centre’s computer (an SEL ER65).

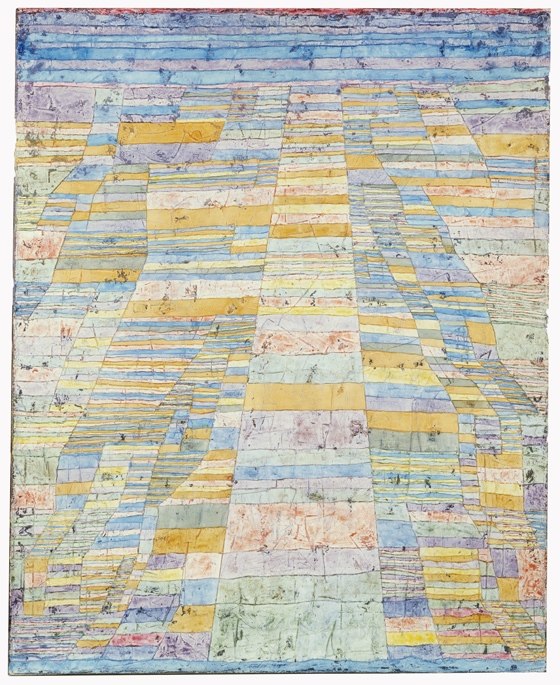

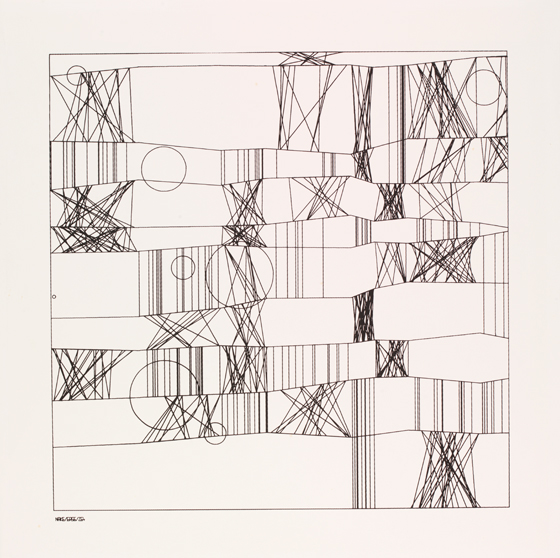

Dating from 1965, Nake’s Hommage à Paul Klee, 13/9/65 Nr.2, of which the V&A holds a screenprint after the original plotter drawing, is an excellent example of Nake’s early exploration of Bense’s theories (fig. 1). The plotter drawing is a literal analysis of an oil painting by Paul Klee, entitled Highroads and Byroads, from 1929 (fig. 2). Klee’s painting consists predominantly of a series of horizontal and vertical lines which Nake used as the basis for writing a computerprogramme, or algorithm. Creating set parameters for the drawing, such as the square frame, Nake deliberately wrote random variables into the programme to explore different visual effects, based on Klee’s ‘repertoire’ of imagery. Nake allowed the computer to make choices from a limited bank of options based on the outcome of the previous decision, thus introducing an element of chance, albeit a controlled one. Theprogramme itself was written in machine code and input directly into the computer, which would have had no interface or operating system at this time. The process of creating the drawing involved a series of formulae developed away from the computer. Nake has written that, ‘I was thinking the drawing. But thinking the drawing never meant to think one particular drawing. It meant a class of drawings, an infinite set, described by many parameters that would usually be selected at runtime by series of random numbers’.12 There was no screen or monitor available on which to preview the drawing, and the final result would only have been apparent when the machine had finished. The final image we see here was just one of many possible variations from a wider series, the most successful of which was determined by the artist.

This literal analysis of aesthetic objects was very much a part of Bense’s theories, and can also be found in the work of other early practitioners of computer art. A. Michael Noll used the computer to simulate Piet Mondrian’s Composition in Line, 1916–1917 Like Klee’s Highroads and Byroads, Mondrian’s painting is an exploration of the relationship between vertical and horizontal lines. Noll analysed the painting and deduced three main determining factors regarding the outline of the design and the length and width of the painted lines, or bars, particularly with relation to their position within the overall composition. Each line provided Noll with two points (the beginning and end of the line) that could be plotted on x and y axes as numerical values. Like Nake, Noll introduced random variables into the computer programme he wrote to emulate the painting, so that the placement of each line and its size and orientation were randomly determined within a set number of options. Noll produced his version in 1964, using a microfilm plotter that controlled a 35mm camera. He called it Computer Composition with Lines, and a photographic reproduction now sits in the V&A’s collection (fig. 3). Noll displayed his version alongside images of the original in order to conduct a series of experiments using questionnaires, the results of which he hoped would,‘determine what aesthetic factors are involved in abstract art’.13

Noll’s attempt to underpin the creative process with a logical procedure is typical of the work of early computer art practitioners. His search for objective rationality was the very antithesis of much of the subjective, gestural, expressionist art that had preceded it, and which art movements, such as Neue Sachlichkeit that had arisen in Germany in the 1920s, had also done much to oppose. Reading Noll’s description of his experiment in an article written in 1966, it is not difficult to see why many in the mainstream art world resented this new art. Noll wrote that, ‘the experiment compared the results of an intellectual, non-emotional endeavour involving a computer with the pattern produced by a painter whose work has been characterised as expressing the emotions and mysticism of its author. The results of this experiment would seem to raise doubts about the importance of the artist’s milieu and emotional behaviour in communicating through the art object’.14

Noll’s choice of Mondrian painting was, unsurprisingly, one that lent itself well to his particular argument, rather than perhaps being truly representative of Mondrian’s larger body of work. The use of a decorative scheme by a fine artist at this time can be seen as part of a wider move away from subjective, emotional content, but its adoption by Noll reminds us that any useful consideration of computer art should also include the wider context of the applied arts and crafts, rather than the fine arts alone. Computer art’s emphasis on form and pattern as opposed to content, the notion of art as applied to a practical end (or at least the possibility of), the application of a mechanical skill, and the importance of materials and tools make an interesting case for considering the computer artist as artisan. Rather than continuous recourse to inspiration, once a computer artist had decided upon their decorative scheme and written their algorithm, the objects could be ‘run out’ mechanically with little involvement of the artist, short of adjusting malfunctioning equipment. The workshop type origination and collaborative nature of much computer-generated art also suggests similarities with craft based arts. Whilst it would be simplistic to imply that the expression of an idea was not important for computer artists, although it was rarely, if ever, of a subjective nature, certainly the sheer creation and crafting of an object - something which was not a natural outcome for the computer - seems to have been at the forefront of many practitioners intentions, at least in the early years.

Noll’s experiments were arguably as much about showcasing the capabilities of this new technology, but there is a clear affinity with the earlier work of the Bauhaus, as reflected in the careful crafting of design, and the belief in a refined beauty as a natural outcome of precise engineering. Max Bense had taught at the Hochschule für Gestaltung (School of Design) in Ulm, Germany, alongside Max Bill, and it was there that he had developed some of his early theories. Equally, Gyorgy Kepes moved from the New Bauhaus in Chicago to Massachusetts Institute of Technology, an institution that, alongside others such as Harvard, had begun adopting Snow’s theories regarding the humanities-sciences divide into its education policies. Josef Albers, whose rigorous colour studies and interest in perception proved to be highly influential on early computer art and systems art, moved in 1933 from the Bauhaus to teach at Black Mountain College, where he joined Merce Cunningham and John Cage, both of whom also exerted a strong influence on the emerging scene.

Computer art’s modernist tendencies

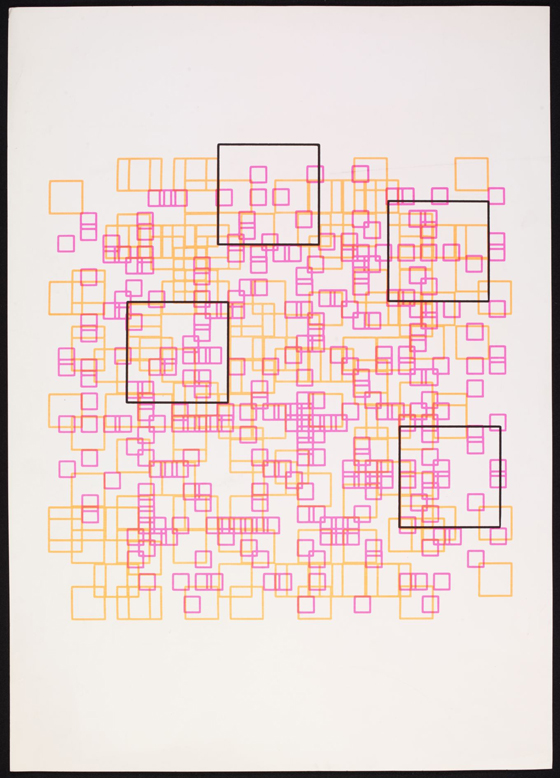

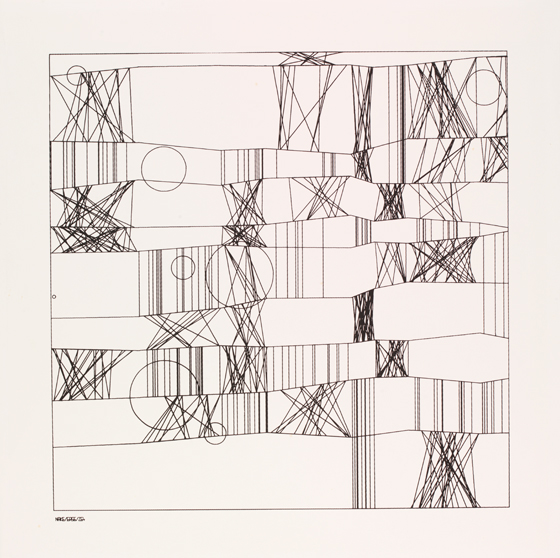

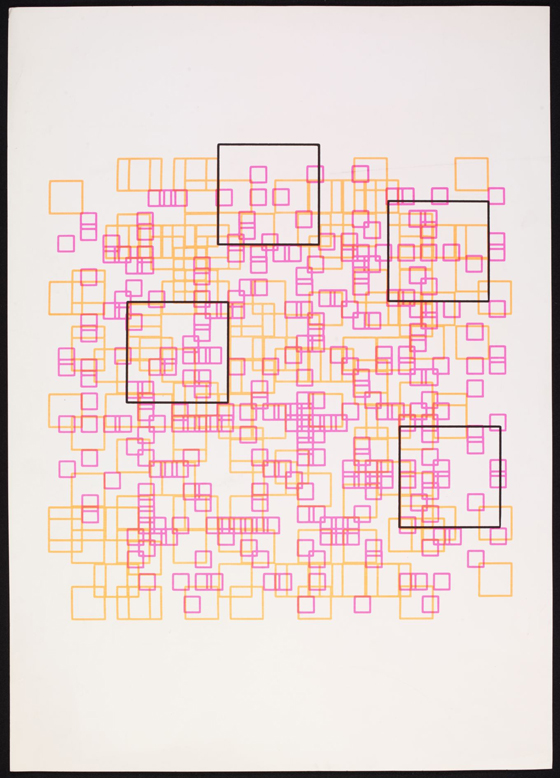

In appearance, early computer art tended to be linear, geometric and abstract, and although, in part, this was a direct result of the limited output devices of the period, it is also possible to see it as part of the Modernist culture out of which it arose. Shared concerns with formalism, lack of ornamentation, rationality and aesthetic autonomy demonstrate that computer art was very much an art of its time. It is perhaps ambitious to draw parallels with Modernism’s belief in the power of the machine and the potential of mass production, but computer art certainly presented a similar interdisciplinary approach that took little notice of traditional boundaries and hierarchies. Instead, it seemed to offer a more democratic approach to art making (at least in later years), that appealed to many budding computer artists. Herbert W. Franke’s Quadrate (Squares), dating from 1969/70, is a good example of computer art’s reductionist approach to visual content (fig. 4). Early works frequently consisted of lines or geometric shapes that were positioned, repeated, rotated and rescaled by the computer, in a manner that echoed the Constructivist principles of several decades earlier.

Early practitioners of computer art tended to avoid content in order to focus on the effects of their visual experiments. The collaborative relationship between the artist and the computer, or the artist and computer programmer, and the shared environment of the laboratory as opposed to the solitary artist’s studio, rejected Romantic notions of the ‘artist-genius’. Equally, in its generative nature, the new computer art threatened the idea of the unique, singular masterpiece, a move in line with Conceptual art’s de-emphasis on the importance of the art object and increased emphasis on process.

Artists as programmers

Many of the practitioners who began working with the computer in the late 1960s and 70s were, by this time, artists with traditional fine art training. What unites many of them is that they were already working in a systematic manner that anticipated the arrival of the new technology. Rules-based creative processes or practice and the setting of constraints or parameters were not new concepts in the arts, even if some of the previous examples had focused more on a personal logic than on the scientific approach of computer artists. By the 1960s and 1970s, many artists were applying a computational methodology to their work whether or not they worked with computers directly, for example Bridget Riley and other exponents of Op-Art.

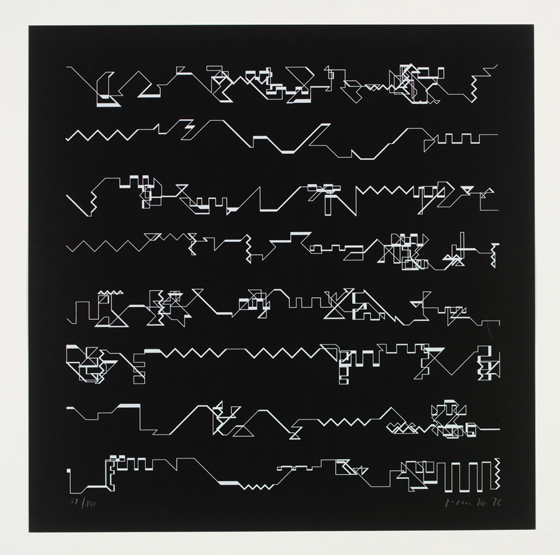

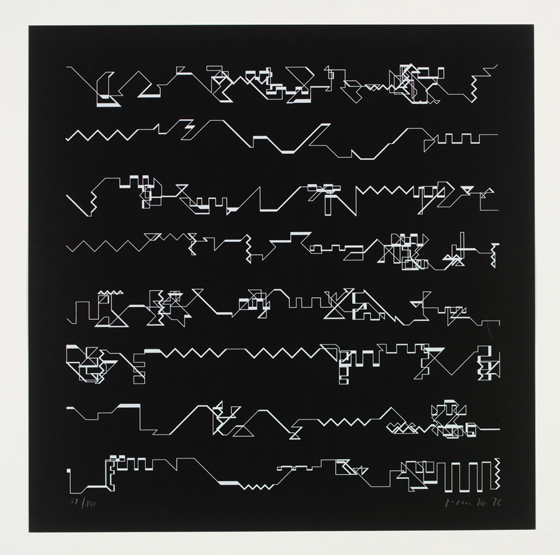

Manfred Mohr, a German artist who began his artistic career as an action painter and jazz musician, moved to Paris in 1963 and a year later began restricting his palette to black and white. Influenced by the hard-edged painting that he found in geometric abstraction and Op-Art, and which presented an alternative to abstract expressionism, Mohr began experimenting with geometric imagery. He was drawn to the computer because of its ability to process large quantities of information very quickly, but also because of the notion of a repertoire that was at the core of its construction. In a method not unlike that of jazz improvisation, Mohr took the signs and symbols from his earlier paintings and used them as the basis of a graphical vocabulary for his computer-generated drawings. Using programmes that he wrote himself, Mohr produced works that explored the relationships of these signs and symbols, mostly linear constructions, to one another, in a style that demonstrated a strong link to Constructivist exploration of spatial relations. The title for Mohr’s screenprint, P-021, taken from a portfolio of screenprints, Scratch Code: 1970-1975, refers to the programme used to create this work, which was capable of generating a large number of related, yet unique, drawings (fig. 5).

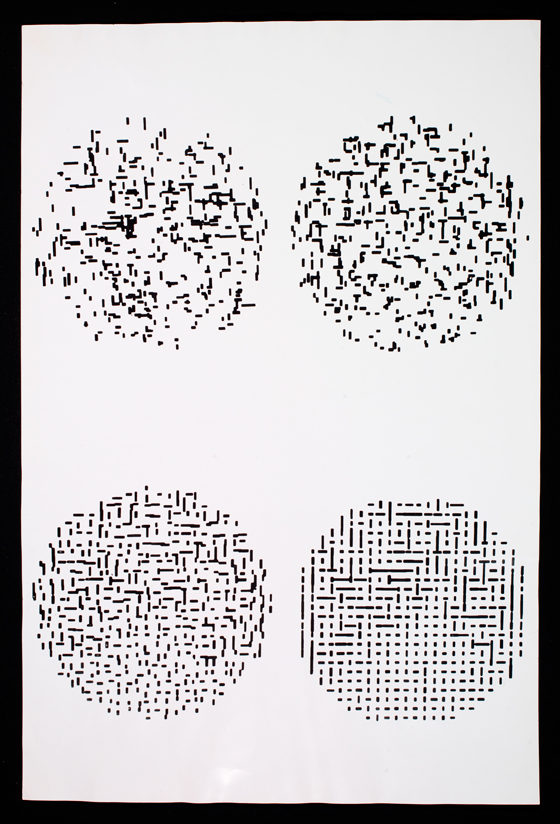

Vera Molnar was living in Paris around the same time as Mohr and was also working in a systematic fashion, using repeating geometric forms and employing small step-by-step changes to explore their visual effects. In 1968, she began working with the computer, also realising its potential for faster information processing and a more objective approach. Letters from my Mother, a series of works from which the V&A holds a 1988 screenprint after two plotter drawings, attempts to simulate her mother’s handwriting and to chart its degeneration as her mother aged and her health declined (fig. 6). The computer programme used by Molnar created a method for accurately simulating the glyphs whilst not formally depicting actual letters or words. The imagery echoes Bense’s theories on the relationship of order to chaos, but with distinctly human overtones. The work is also a compositional study in which Molnar sets the increasingly chaotic nature of the ‘writing’ against classic compositional strategies such as symmetry and counter composition. This piece illustrates well the relationship between artistic intuition and a more objective control, which Molnar felt made an equal contribution to the process of creating art using the computer.

Computer art in America

A. Michael Noll had exhibited his computer art in New York in 1965, the same year as Nake and Nees were, independently of one other, also exhibiting their own work in Germany. It is believed that Noll was not aware of the European developments. In fact, communication between computer artists in North America and Europe was not strong in the early years and the two scenes appear to have developed relatively independently of one another. America was particularly strong in the field of computing technology, following heavy military investment during WWII. Bell Labs (originally Bell Telephone Laboratories) was founded in 1925 and was home to many of the key American computer art pioneers. These included A. Michael Noll, whose first computer art experiments were carried out under its roof, as well as others such as Ken Knowlton, Leon Harmon and Edward Zajac, all of whom were particularly instrumental in developing early programming languages and computer animation. The Patric Prince and Computer Arts Society collections both hold excellent examples of many of these early developments.

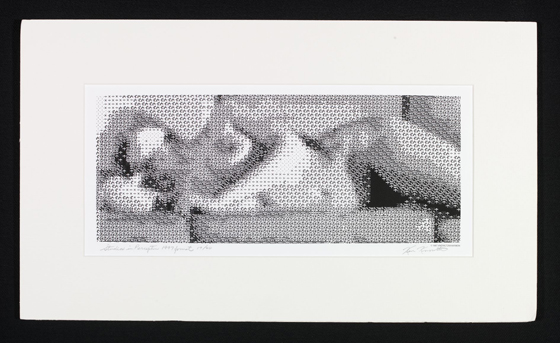

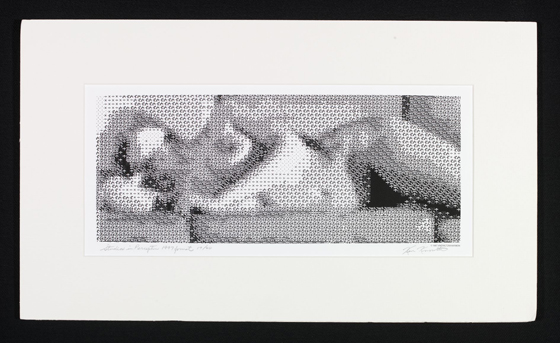

Leon Harmon and Ken Knowlton were responsible for developing automatic methods for producing digital images. Whilst at the labs, they created a twelve foot long digital print of a female nude by scanning a photograph and converting the grey scale values into computer symbols.15 The image, entitled Studies in Perception I (1967), was so large that its subject matter was only apparent at a distance. What began life as a work prank to be hung in the office of a senior colleague found fame when it featured in the background of a press conference held in the loft of Robert Rauschenberg. As a direct result, the piece was reproduced in The New York Times. The legacy of the work led to the creation of a much smaller, limited edition print produced in 1997 and collected by Patric Prince (fig. 7). A rare example of the commercial potential of early computer art, its late reproduction is also indicative of the renewed interest in this field in more recent times.

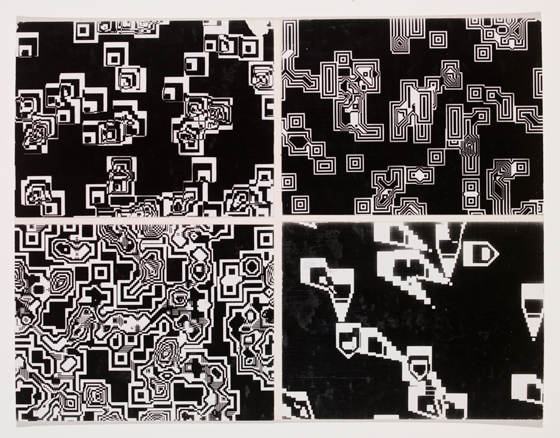

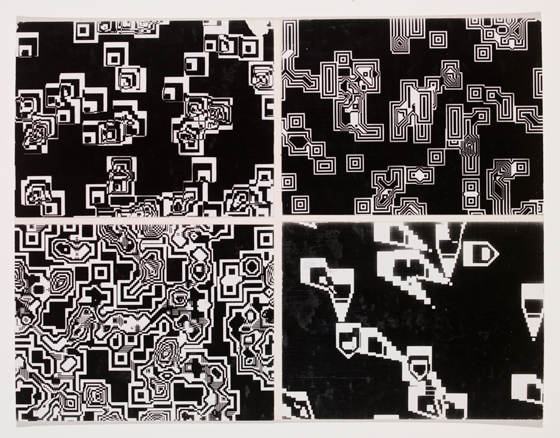

Knowlton was also responsible for developing some of the earliest computer animation languages, such as BEFLIX (from Bell Flicks) created in 1963. He collaborated with artists such as Stan Vanderbeek and Lillian Schwartz, for whom he adapted his programming languages. The Computer Arts Society collection holds a number of examples of Knowlton’s collaborations with Schwartz, including stills which were taken from their computer animation, Pixillation, produced in 1970 (fig. 8).

Bell Labs was also home to Billy Klüver who collaborated with Robert Rauschenberg to form EAT (Experiments in Art and Technology) following a series of performances that took place in New York in 1966. The events were entitled 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, and engineers from Bell Labs collaborated with 10 artists to help them realise the technical aspects of their performances. Klüver encouraged artists and musicians to use the facilities at Bell Labs out of hours. EAT did much to increase interest in the relationship between art and technology in the mainstream art world. In 1966 Maurice Tuchman introduced the Art and Technology programme into the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which saw him emulate the collaborative approach of EAT by placing artists in US corporations to realise artistic projects. For example, Richard Serra worked with Kaiser Steel, R. B Kitaj joined the American aerospace company, Lockheed, and Claes Oldenburg went to Disney. Exhibitions such as The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age, at MOMA, New York, followed shortly afterwards, in 1968.

‘Cybernetic Serendipity’ and the role of the British art education system

In Britain, 1968 had already seen the opening of Cybernetic Serendipity at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and, just months later, the founding of the Computer Arts Society. Cybernetic Serendipity was a showcase for the use of technology in the arts - the first of its kind in Britain - and incorporated both computer-aided and computer-inspired art. The exhibition covered many different art forms, including music, film, kinetic art, robotics, dance, poetry and sculpture. It featured the work of both artists and scientists, as well as displays by corporations such as IBM. There were 325 contributors in total. Interest in the show was high, with visitor numbers between 45,000 and 60,000.16 The exhibition also had a profound impact on many artists who went on to use computers or technology in their work.

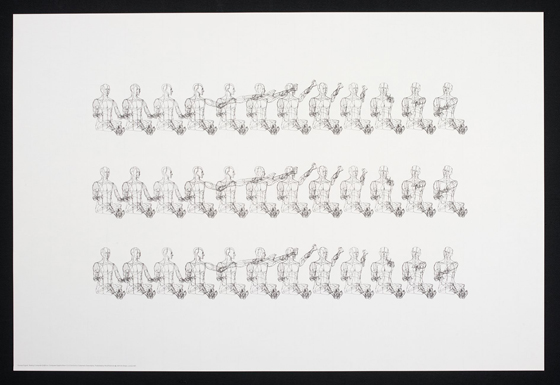

The success of Cybernetic Serendipity implies that there was still some sense of the previously felt utopianism and optimism surrounding computers and technology. This, it seems, was to be short lived and the emerging dystopian vision of computing technology that followed soon after contributed much to computer art’s retreat and relative obscurity in the following decades. Gustav Metzger, who went on to edit the Computer Arts Society’s journal PAGE, criticised the exhibition, writing that there was, ‘no hint that computers dominate modern war; that they are becoming the most totalitarian tools ever used on society’.17 A collector’s set of prints published by Motif Editions as part of the exhibition, and acquired by the V&A in 1969, seems to offer examples of both viewpoints. William Fetter’s Human Figure (1968), depicts a line drawing of a male figure repeated twelve times, in which, step by step, he extends his left arm out to the side and back across himself (fig. 9). The computer drawing was an ergonomic study conducted for Boeing, where Fetter worked as Art Director, to test the movement of an aeroplane pilot in a cockpit. The original version of this image was produced in the early 1960s and is said to be the first drawing of a human made using a computer. It contributed directly towards designs for the Boeing 747. Although the figure is known as the ‘Boeing Man’, Fetter apparently referred to him as the ‘First Man’, an indication perhaps of the scientific potential of the new computer graphics.18

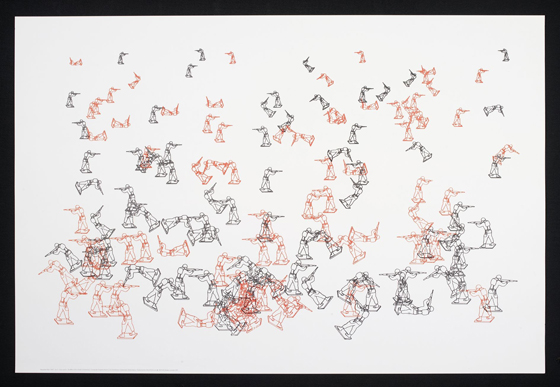

In contrast to this, Charles Csuri’s Random War examines the use of systems as an organisational metaphor for society (fig. 10). Csuri used a random number generator to distribute and position images of toy soldiers. The print is derived from a much larger work in which the computer programme designated each soldier a status of killed, wounded, missing, awarded a medal or survived. Each soldier was named, and they included, amongst others, Charles Csuri himself, but also Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford. Csuri had witnessed the effects of war first hand, serving with the US army in Europe during World War II. The work is undoubtedly a comment on the Vietnam War and was made in 1967–68, when anti-Vietnam War sentiment was at its height.

Cybernetic Serendipity revealed the extent of the impact that cybernetic thinking had had across a broad range of disciplines, and the exhibition did much to cement these ideas into the British Arts scene. Art historian Catherine Mason has argued that it encouraged the adoption of creative computing into the art curriculum, particularly in Britain’s polytechnics, where computing equipment was more common because of their emphasis on vocational training.19 For example, in 1971, Lanchester Polytechnic (now part of Coventry University), was one of the earliest institutions formally to introduce computer drawing into its graphic design course. Middlesex University was another key institution, becoming in 1984 the UK’s National Centre for Computer Aided Art and Design. In the early 1970s, the Slade School of Art, University of London, founded what came to be known as the Experimental and Computing Department, which actively encouraged the use of computers in art.

The Slade’s adoption of technology at a time when this was rare amongst other, more traditional, art schools can be explained via the influence of a number of key students and staff, not least several members of the Independent Group, such as Richard Hamilton and Eduardo Paolozzi. They had been quick to adopt ideas around cybernetics and demonstrated an early fascination with technology as subject matter. William Coldstream was Slade Professor from 1950 to 1975, and his active support of the establishment of the Experimental and Computing Department has been attibuted, in part, to his having worked at the General Post Office Film Unit in the mid-1930s, which was an important European centre for the production of experimental film. Teaching staff also included Harold Cohen, who was a successful painter before he turned to the computer in the late 1960s. Although Cohen began teaching in 1962, several years before he started working with the computer, his early artworks demonstrate an interest in systems and information, as applied through logical processes. In a computer print-out with hand drawn coloured pen and ink, dating from 1969, now in the V&A’s collection, Cohen used a coloured pen to identify and group computer printed numbers to form a type of contour map (fig. 11). It antipates Cohen’s later work in developing a computer programme, AARON, that aims to draw independently and which is yet another example of early computer artists’ attempts to rationalise, and here codify, the creative process. The instigator of the new Slade department was Malcolm Hughes, who had been a co-founder of the Systems Group in 1969 and whose work reflected Constructivist concerns with structural relationships, rhythm and order. Alumni of the department include, amongst others, Paul Brown, a British artist whose work is held in the V&A’s collection, and who, like many of his peers, demonstrated an early interest in cellular automata and artificial life.

In the UK, increased access to computers and their integration into art education did much to advance the field of computer art. Towards the end of the 1970s, however, government investment in educational institutions was reduced. This coincided with a recognition in the worlds of advertising and television that the polytechnics held the skills needed to take on the demand for commercial work in this area.20 It was the beginning of computer graphics as a commercial enterprise that was to expand rapidly in the 1980s and which signalled the end of an era for computer art. The impact that the work of the last two decades would have on generations of artists and designers to come could not have been truly predicted at the time. The collection of computer art at the V&A and the allocation of AHRC funding allows for a long overdue reappraisal of this field of art and design and an opportunity finally to place it on the art historical map.

Acknowledgements

This article has been produced as part of the AHRC funded research project, Computer Art and Technocultures, at the V&A and Birkbeck College, University of London. I am particularly grateful to Douglas Dodds, Senior Curator, Word and Image Department, V&A, and Nick Lambert, Researcher in Digital Media Arts, Birkbeck College, University of London, for their assistance.

Endnotes

This journal article was updated in October 2016.

-

Decode: Digital Design Sensations is co-curated with digital arts organisation onedotzero. More information on the exhibition can be found here (accessed 19 October 2009). ↩︎

-

The Computer Arts Society was founded in 1969 to promote the creative use of computers in the arts. More information can be found here (site accessed 19 October 2009). ↩︎

-

Patric Prince is an American art historian and collector of computer art. She taught at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, California State University, Los Angeles, and West Coast University, Los Angeles. In addition, she curated many significant exhibitions of new media art since the early 1980s, including several for SIGGRAPH (Special Interest Group for Computer Graphics), and was co-director and founder of CyberSpace Gallery in West Hollywood. ↩︎

-

Further information on these artists can be found in the following publications and online resources: Harold Cohen: Exhibition catalogue, Michael Compton, ed. (London, 1983); James Faure Walker: Painting the Digital River: How an Artist Learned to Love the Computer (New Jersey and London, 2006); Desmond Paul Henry; Roman Verostko; Mark Wilson ↩︎

-

See http://catalogue.nal.vam.ac.uk (site accessed 20 October 2009). The entire collection of bibliographic material can be found by searching under ‘Patric Prince Archive’. ↩︎

-

It is interesting to note that a selection of computer-generated art featured in the Venice Biennale in 1970. These included works by Herbert W. Franke, Frieder Nake, Georg Nees and the Computer Technique Group (CTG), all of whom are represented in the V&A’s collections. Although this offers some indication of the extent to which computer art had begun to enter the more mainstream art world, art historian Francesca Franco has argued that the exhibition can be considered to be something of an ‘anomaly’ and its presence partly explained by an increased pressure on the Biennale ‘for the democratisation of art’ that led to a more experimental approach to its curation. Franco, Francesca. The First Computer Art Show at the 1970 Venice Biennale. An Experiment or Product of the Bourgeois Culture? Unpublished conference paper presented at Re:live, Third International Conference on the Histories of Media Art, Science and Technology, Melbourne, 26–29 November 2009. (Forthcoming publication in Leonardo). ↩︎

-

Taylor, Grant. The Machine that Made Science Art: The troubled history of computer art 1963–1989. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Western Australia, 2004: 4. Available online http://theses.library.uwa.edu.au/adt-WU2005.0114 (site accessed 20 October 2009). ↩︎

-

‘Computer Does Drawings: Thousands of lines in each’. The Guardian, 17 September, 1962. Article reproduced in O’Hanrahan, Elaine. Drawing Machines: The machine-produced drawings of Dr D. P. Henry in relation to Conceptual and Technological developments in machine-generated art, UK, 1960–1968: appendix 13 - copies of newspaper reviews relating to Henry’s artwork. Unpublished, 2005: 217. ↩︎

-

Although the social consequences of technology would have been highlighted through the use of computers in the Cold War and again in the Vietnam War, theorist Charlie Gere has suggested that artists and musicians from this period, such as John Cage, ‘offered a framework in which the technologies of Cold War paranoia could be translated into tools for realizing utopian ideals of interconnectivity and self-realization. (Gere, Charlie. Digital Culture. 2nd. ed., London, 2008: 116). Gere suggests that from the late 1960s until the mid 1970s, the use of computers by artists was part of a larger realisation that technology offered a push towards a ‘post-industrial society’ that would bring with it "new forms of social organization’. (Gere, Charlie. Digital Culture. 2nd. ed., London, 2008: 116). This meant less focus on the service sectors and greater emphasis on information and knowledge exchange - something which was felt to be a positive, natural development. (Gere, Charlie. Digital Culture. 2nd. ed., London, 2008: 116). Technology was recognised as a positive force in the work of theorist Marshall McLuhan and the architect Buckminster Fuller both working at this time. Gere goes on to note that similar views were also to be found within the avant garde. (Gere, Charlie. Digital Culture. 2nd. ed., London, 2008: 118). ↩︎

-

Snow, C. P. The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution, The Rede Lecture 1959. London and New York, 1959. ↩︎

-

Guy Ortolano examines what he describes as ‘the runaway success of the two cultures’, as well as the resulting conflict that arose between Snow and F. R. Leavis, in his article Leavis, F. R. ‘Science, and the Abiding Crisis of Modern Civilisation’. History of Science vol.43, 2005: 161–185. He notes that the success of the lecture was in part explained by ‘enabl[ing] commentators to pursue an extraordinary range of concerns’ from ‘the importance of education to Britain’s future, and the industrialization of the developing world’ through to such substantial issues as the space race. Leavis, F. R. ‘Science, and the Abiding Crisis of Modern Civilisation’. History of Science vol.43, 2005: 164–5. ↩︎

-

The relationship between aesthetic theory and artistic practice with relation to the Stuttgart School and Max Bense has been covered extensively by Christoph Klütsch in his PhD thesis, Computergrafik - Aesthetische Experimente zwischen zwei Kulturen (Computer Graphics - Aesthetic Experiments between Two Cultures). University of Bremen, 2006. ↩︎

-

Nake, Frieder. ‘Without a Screen: A remark on technical conditions of digital art in 1965’. A statement sent in an email to the author, 6 July 2009. ↩︎

-

Noll, A. Michael. ‘Human or Machine: A subjective comparison of Piet Mondrian’s Composition with Lines(1917) and a computer-generated picture’. The Psychological Record 16 (1966): 1–10. Available online: http://noll.uscannenberg.org/Art Papers/Mondrian.pdf (site accessed 20 October 2009). ↩︎

-

Noll, A. Michael. ‘Human or Machine: A subjective comparison of Piet Mondrian’s Composition with Lines(1917) and a computer-generated picture’. The Psychological Record 16 (1966): 9–10. Available online: http://noll.uscannenberg.org/Art Papers/Mondrian.pdf (site accessed 20 October 2009). ↩︎

-

The subject of the photograph was Deborah Hay, an important experimental choreographer of the time whose influences include both John Cage and Merce Cunningham. ↩︎

-

Mason, Catherine. A Computer in the Art Room: the origins of British computer arts, 1950–1980. Norfolk, 2008: 101. Mason draws comparison with the exhibition of Matisse paintings that opened at the Hayward Gallery in July of the same year which attracted 114,214 visitors. ↩︎

-

Metzger, Gustav. ‘Automata in History’. Studio International. New York, 1969: 107–9. ↩︎

-

Carlson, Wayne. A Critical History of Computer Graphics and Animation, Section 2: The emergence of computer graphics technology. http://design.osu.edu/carlson/history/lessons.html (site accessed 20 October 2009). ↩︎

-

Mason, Catherine. A Computer in the Art Room: the origins of British computer arts, 1950–1980. Norfolk, 2008. ↩︎

-

Mason, Catherine. A Computer in the Art Room: the origins of British computer arts, 1950–1980. Norfolk, 2008. 169. ↩︎