Abstract

Production of white quilted furnishings existed in the Middle Ages throughout most of Europe and certainly in France. Refined work with story-telling motifs is associated principally with southern Italy, renowned examples being the fourteenth-century Tristan quilts, which will be exhibited by the V&A in November, 2009, and at the major Quilts exhibition from 20 March to 4 July 1010. This paper looks at the cultural environment of the Tristan quilts, their precursors and the white motif-laden confections that followed them.

The young couple, newly smitten and alone in a castle, approached her bed, ‘with its coilte or quilt, finely-made of two layers of rich cloth worked in a checkered pattern.’1 This seduction scene, in a twelfth-century French poem, illustrates the story with handsome textile furnishings. The reverse was also true during the Middle Ages - handsome furnishings held imagery from popular stories. Surviving decorative objects made for churches, halls and residences reflect the aspirations, beliefs, educational levels, and loyalties of the medieval elite.

Prime examples are the two Tristan quilts in the V&A, London, and in the National Museum of Bargello, Florence. They are both white corded and quilted works, showing episodes from the Norman legend of Tristan, and attributed to a Sicilian atelier in the late fourteenth century. Although these two pieces are mentioned frequently in recitals of quilt history, a review of medieval art, history, materials, patronage and values lends insight into their making, and into the continuing tradition of all white corded and quilted textiles.

The Norman Conquest: Bayeux Tapestry

An early story-telling textile, the eleventh-century Bayeux Tapestry (fig. 1) depicts the Norman conquest of England by William in 1066.2 Embroidery in chain, stem, and couching stitches, using polychrome wool on linen, portray events leading to and including the Battle of Hastings. An illustrated account of oaths of fealty, sea-crossings, feasts, violent battle, heroic acts, and the gore of hand-to-hand combat appears over its grand length (230 feet by 20 inches in height). Latin text in the vignettes identifies the heroes, villains, and action of the scene. Borders at top and bottom portray beasts, birds, fables, ornaments, and figures engaged in farming, hunting and erotic behavior. Battle scenes surmount images of fallen soldiers, crippled horses, soldiers stripping the dead of their armour and not a few decapitated bodies.

The identities of who ordered the work, who made it and where, and even its original destination, are unknown. The earliest documentation of the Tapestry, in 1476, reveals it was mounted annually in Bayeux Cathedral at the feast of Corpus Christi. The rest of the year it was rolled on a drum, possibly to allow easy transport for display in other venues. The embroidery’s portability may have been purposeful, to bring the powerful story of the Norman Conquest to as many people as possible.3

R. Howard Bloch writes, ‘Part of the enduring effect of the Tapestry…has to do with the power to integrate so much and so fully the various strands of imagery and meaning available at the time of its creation’. Bloch calls the Battle of Hastings a critical moment that determines the future of medieval Europe and the beginning of the era of the knight.4

Norman Sicily: the Otranto Cathedral pavement

The era of the knight was also the era of the Crusades, and Normans were major participants. A political consequence of the Crusades was access to valuable lands in the Mediterranean region. By 1130 Roger II had carved a Norman kingdom in southern Italy and Sicily, where he inherited a rich artistic legacy. Prior centuries of Greek, Byzantine, and Arab rule in southern Italy were marked by the production of luxurious material goods. Patronized by European nobles, deft Palermo artisans had crafted magnificent textiles, jewels, coinage and decorative objects, with imagery drawn from the mix of cultures. Norman rule contributed legends, myths and adventure tales culled from lands they had conquered, all of which entered into the design repertoire of the artisans of Sicily and Naples.

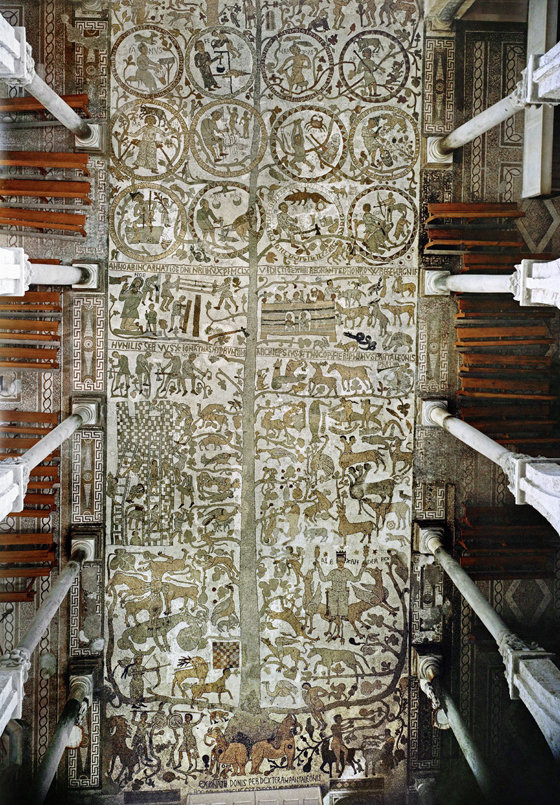

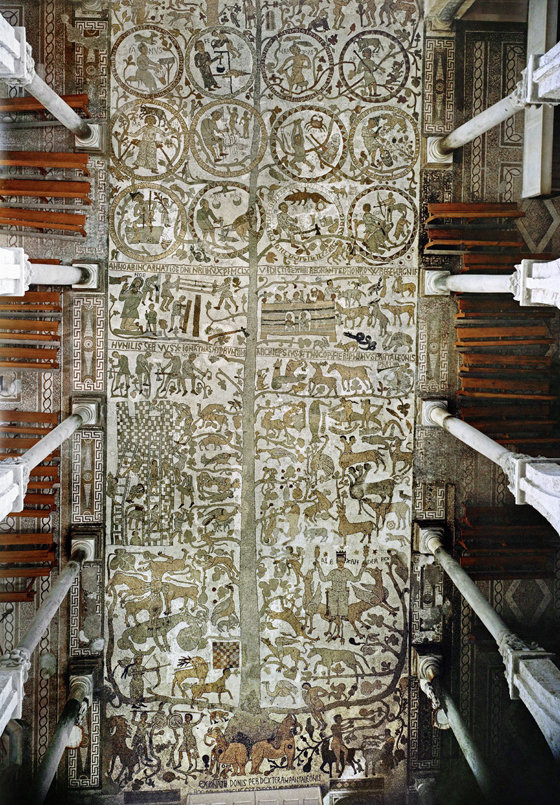

The mosaic floor in the Cathedral of Otranto, Italy, is an encyclopedia of these conjoined legends and beliefs, all laid out for public witness (fig. 2).5 The composition, designed in 1163 by a monk named Pantaleon, blends moral instruction from the Koran and the Old Testament with tales of Celtic, Greek, Norman, Persian, Roman, Scandinavian, and Welsh origin, in confirmation of the wide dispersion of these stories and the images associated with them. The pavement scenes show familiar figures in action. A serpent hisses his offer to Eve, Cain slays Abel, the Queen of Sheba romances Solomon, the goddess Diana tracks a deer, Alexander the Great ascends to heaven, King Arthur (fig. 3 ) salutes from atop a beast and, in a nod to ordinary folk, a calendar shows labourers engaged in appropriate monthly toil, overseen by the appropriate zodiac sign. Fantastic animals and birds mingle with more realistic counterparts - fish, goats, horses and owls - throughout the pavement. Just below the altar, a two-tailed mermaid spreads her tails to each side in salacious invitation (fig. 4) . The identities of key characters are picked out in tiles, for example, ‘Rex Arturus,’ ‘Abel’, and ‘infernus Satan’, to ensure no confusion. The prominence of King Arthur and Alexander the Great in the mosaic bears witness to Norman claims of ancestral ties to these legendary figures.

Norman legend in textile furnishings: the Tristan quilts

Although Sir Tristan appears in neither the Bayeux Tapestry nor the Otranto mosaic, his hour was nigh. A Norman narrative of the Tristan legend surfaced around 1150, to be quickly embellished and dispersed. This riveting tale of irresistible love constrained by knightly loyalty, and leading to doom, pervaded medieval culture.6 Sicilian needleworkers were under Norman House of Anjou rule between 1360 and 1400, when the order for the Tristan quilts was given. Their needle skills were already highly developed. The Tristan quilts are exemplars of successful manipulation of a flat textile with needle, thread and filling to create a three-dimensional surface with significant, legible patterns. The imagery stitched in the quilts relates episodes from Tristan legend in vivid, masterful detail, bringing domestic intimacy to one of the most popular tales that captivated medieval Europe (fig. 5).

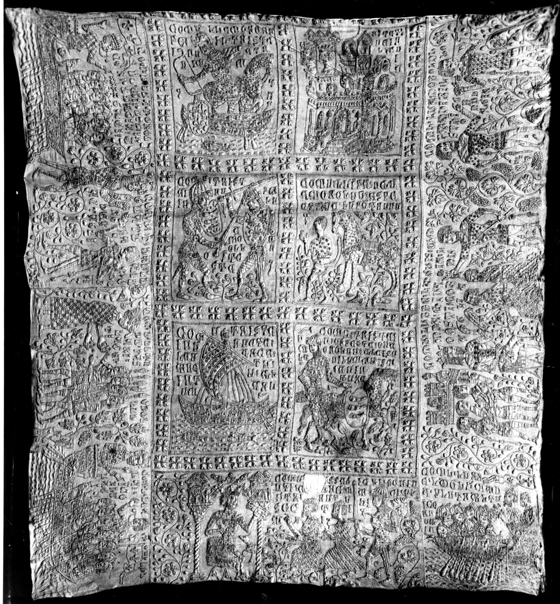

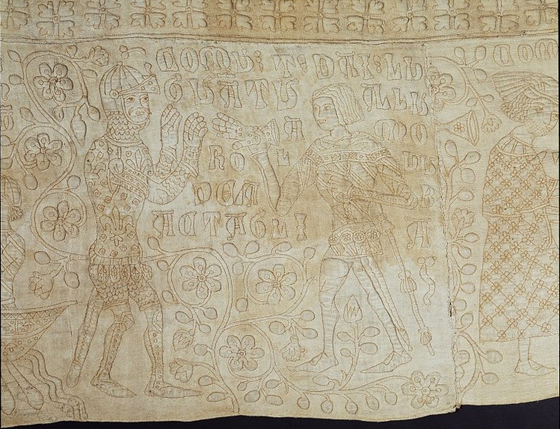

Between them, the two V&A and Bargello Tristan quilts depict episodes in which the young knight addresses and resolves a major conflict between Mark, King of England, and Languis, King of Ireland. Bargello quilt borders portray Tristan leaving the court of his foster father for that of his uncle, Mark, King of Cornwall. V&A quilt borders portray Mark conferring knighthood on Tristan, the demand of tribute from Mark by King Languis of Ireland, Tristan’s defiance of the demand, declaration of war, and Tristan’s challenge to the Morold, Languis’s champion. Panels in the middle of both quilts depict the two knights as they arrive for combat (Bargello), Tristan thrusting away his own means of escape (V&A), the two men battling on horseback (Bargello), Tristan as he smites the Morold on the head, and the villain’s cowardly sneak attack on Tristan (both V&A) (fig. 6).7

Text, in Sicilian dialect, spells out who’s who, for example, ‘How Tristainu smote the Amorolldo in the head’. Top and backing of both Tristan quilts are linen of excellent quality, proven by their survival for over six centuries. Motifs are worked in running and backstitch using dark brown, light brown, and white linen thread. Cotton batting fills both quilts (fig. 7).8 Medieval aristocrats were drawn to Tristan’s persona: high-born, then orphaned and kidnapped as a youth, intrepid and skilled as a soldier, loyal to God and king, ardent yet discreet as a lover. In 1250 Queen Margaret, wife of Louis IX, captive in Damiette, Egypt, while her husband led a Crusade east of the Nile, invoked Tristan’s ability to overcome obstacles by naming her newborn son Jean Tristan, ‘because he was [also] born in sadness and poverty’.9 The knight’s fine qualities were similarly invoked in the order given to the Sicilian needlework atelier. Both Tristan quilts and a third piece attributed to the same atelier, show the arms of the Guicciardini family: three horns imaged on the knight’s shield.10 Thus, the hero’s valiant deeds and sterling character reflect on the noble patron who ordered this image-laden work.

White tabula rosa: luxury cottons

Modern consumers might not consider cotton or linen an appropriate textile for an aristocrat’s special order. But witness the regard these textiles attract from medieval writers. ‘Whitest of white’ is Giovanni Boccaccio’s description in ‘Decameron’ (1349–52) of a bedcover made of ‘bucharame’ from Cyprus.11 ‘Bouqueran’, ‘bougran’, and ‘bucherame’ are varied spellings for this fine medieval textile woven of cotton or linen, and sometimes both of these fibres. In 1271 Marco Polo called the ‘bougran’ from Arzinga, now in modern Turkey, ‘the best in the world’. Ibn Battuta agreed by calling Arzinga bougran ‘fine stuffs’ (1334).12 ‘Futaine’ or fustian, a textile woven with linen warp and cotton weft, was also valued. A woman in Eustache Deschamps’s fourteenth-century poem, ‘Le Miroir de Mariage’, emphasises her status by saying, ‘I still wear a camisole of fustaine, my lord’.13

Sicily’s port of Palermo was a major entrepot for textile trade, exporting its own domestic raw cotton (a legacy of Muslim rule), and importing and re-exporting high quality woven cottons produced as near as northern Italy and as far as Syria.14 Sicilian merchants traded in textiles at annual fairs in Champagne and Paris, France, events that served all of Europe. These fairs were the likely source of raw cotton to plump the mattresses of French kings (1316 and 1342) and for the 32 ‘livres’ of cotton, tapestry merchant Jacques Dourdin (Paris, 1403) supplied to Margaret of Flanders, some of it used to fashion two ‘courtepointes’ or quilts for the birth of a grandchild (fig. 8 ).15

Medieval bed quilts

Textile historian Sarah Randles presents a forceful case that the two Tristan quilts were originally joined in one large quilt. Randles’s work reorganizes the sections into a quilted diorama (with significant sections missing), reading counterclockwise in the border, the central images paired and reading from bottom to top. Dimensions of the Randles plan are monumental, up to 6 metres high by 4 metres wide. Randles argues that a large quilt is appropriate for large fourteenth-century Italian beds, but allows the possibility of a different original purpose.16

Early documents reveal that members of French society with money, title, or simple direct access to luxury goods, owned bed quilts. The 1297 estate of Marseilles ship captain Guillaume Ferrenc lists a ‘courtepointe’ among other bed furnishings.17 The 1317 bills of Philippe le Long, list a ‘coustepointes des pieds’, or a small throw. The estates of two members of Provencal nobility register quilted bedcovers in 1360 and in 1397.18 At her death in 1328, Clemence of Hungary, widow of Louis X, left bed furnishings made in white ‘bougran’ (the fine cotton Boccaccio wrote about), a ‘courtepointe’, tester, valances, and curtains.19 Clemence was the daughter of the king of Hungary, her aunt was Marguerite of Anjou and Sicily. Perhaps her bed chamber furnishings came through Sicilian cousins. Jeanne de Laval, wife of Rene of Anjou, King of Provence, Sicily and Naples, had twenty-nine ‘lodiers’ (heavy quilted bedcovers) and a ‘coe[r]tepointe’ in her chateau in northern France in 1471.20

Documents that describe both textiles and motifs in a single object help us form a mental picture of medieval quilts. Three ‘courtepointes’ made of ‘bougran’, one stitched with images of a horse bearing arms, appear in the 1334 inventory of the Hotel of Quatremares, Marseilles, owned by a member of the House of Anjou. Angevin Charles V’s 1380 estate lists four white cotton or linen ‘courtepointes’, one with compass and rosette motifs ‘worked in small stitches’, the second stitched with wave motifs, a third made of 'white cotton with white silk bands, and the fourth ‘skillfully worked’ in animal figures.21 The 1432 estate of Guillaume Renguis, Avignon, records two large white quilted bedcovers, one ‘of fine [cotton or linen] worked in waves similar from one side to the other’.22 Pieces worked with all-over patterns, such as compasses and rosettes, diamonds and waves, were likely to have been bedcovers. The Marseilles piece with heraldic images and the Avignon quilt showing animal figures could have been made for another purpose. Note all of the owners mentioned are either members of the House of Anjou or residents of Provence.

Medieval quilted hangings

Some textiles do not make good bedfellows. For example, ‘boucassin’ is defined as hemp cloth in a 1723 commercial dictionary.23 Two finely stitched white ‘courtepointes’ in Charles V’s 1380 estate were fashioned from ‘boucassin’. Doubtless the king did not tuck in under woven hemp. Quilted works made of unrelenting ‘boucassin’ and showing large-scale motifs make better wall hangings than bedcovers. Quilted hangings, like woven tapestries, were decorative insulation for castle interiors. The imagery worked within them reinforced social identity. Throughout the Middle Ages writes art historian Henry Havard, ‘the halls of French lords were hung with magnificent hangings of wool and silk…and stuffed, or to use the term used then, Contrepointés’.24

Recent research conducted on the Bargello Tristan quilt indicates that it may have served as a hanging. Ultra-violet light tests of the back of the quilt reveal traces of calcium that could have resulted from its placement on a wall. 25 A fourteenth-century Italian citation specifically identifies a quilted hanging. Bartolomeo Boscoli (Florence, 1386) owned ‘une coltre ciciliana di drappo cum armi’ or a quilted Sicilian hanging showing heraldic arms.26 Decorative arts historian Peter Thornton confirms the use of textile hangings in medieval Italy, citing Bocaccio, ‘when he wants to describe a beautifully decked out dining room he speaks of how delightful it is to see the capoletti hanging around the room’. Thornton states many hangings were made from linen woven in Reims and Cambray, others were made of cotton.27

Quilted hangings were draped in the streets on ceremonial and saint’s days in fourteenth-century France. A contemporary poet, Robert le Diable, writes, ‘On the streets before him hung | Pailes, tapis et keutespointes, | All of them stretched as if joining hands’. ‘Kieute’ and ‘kieutepointe’ are variations of ‘courtepointe’, ‘serving both to cover beds and to decorate walls’, according to Havard.28

Makers, origins and imagery

Professional quilters confected high quality bedcovers and hangings used by the medieval elite. Paris guild registries in 1292 note eight ‘courtepointiers’ and twenty-four ‘tapissiers’, all engaged in the commerce of quilting. As a rule, ‘courtepointiers’ made bedcovers and ‘tapissiers’ made hangings, but the rule was often bent. Jehannot, Gautier de Poullegni, and Denise were ‘tapissiers du roi’ to Philippe le Long, but Havard states they were ‘nothing else but courtepointiers’. Other kings also had their own quilters, for example, Thomas de Challons served King John (1352), Martin Didélé served Charles VI (1387), and King Rene had three (1480).29

There were international sources as well for quilted works. An Indian sultan presented traveler Ibn Battuta with two silk ‘courtepointes’ when he arrived in Delhi in 1334.30 Charles V’s reception chambers held quilted hangings and bedcovers described as from ‘outremer’, or overseas, and ‘sarrazin’, from the Near East. Bernart Belenati, an Italian merchant who operated in Paris, supplied this same king with lengths of velvet for a ‘coulte pointe’ (1369). A 1519 inventory from the Chateau de Pau, owned by the House of Navarre, lists two quilted bedcovers in ‘olbre morique’ or work of the Moors, and two quilted testers made of white ‘boucassin’, ‘the work of Italy’.31 While it is tempting to assign the origin of the testers to Italy, the description may indicate the origin of the quilting technique used to make them and not where they were made.

Similar prudence is required when considering inventory references to Naples and Sicily, unless the origin is precisely stated as they are in the following two cases. In 1413 King Robert of Naples sent two ‘coute-pointes’ from Italy to Catherine de Bourgogne in France.32 Nicolas Fagot transported ‘tapisseries’, books, and paintings from Naples to Charles VIII’s chateau in Amboise in 1495, the year Charles claimed Naples as part of his realm.33 However, three ‘courtepointes’ belonging to Elipde, Countess d’Avelin, one with the story of Solomon, a ‘better’ one with the story of Alexander, and the third ‘beautiful, large, and good’ covered with fleur de lys, and all identified as ‘the work of Naples’ (Provence, 1426), may be imitations of the Neapolitan technique stitched by domestic artisans or even the countess herself (fig. 9).34

Rene of Anjou filled his Provencal chateaux with all the arts, including figurative textiles. Scenes of a dozen knights, gentlemen, and ladies appear on two large textiles, with matching scenes worked on two ‘contrepointes’ according to a 1488 inventory of the king’s manor in Perignan.35 Rene could have brought them back from one of his voyages to Naples, ordered them made by his ‘tapissiers’, or had a more intimate source. His widow, Jeanne, still Queen of Sicily at his death in 1480, ordered a large frame for working with textiles from court carpenter Jean Guillebert.36 Did the Queen console herself by working a ‘courtepointe’ on this frame? She is said to have stitched a white piece showing the story of Alexander, in similar style to the Tristan quilts, witnessed on display at Chateau Falque in Marseilles as recently as the early 1900’s.37

Medieval motif repertoire: the Toiles Brodées of Reims

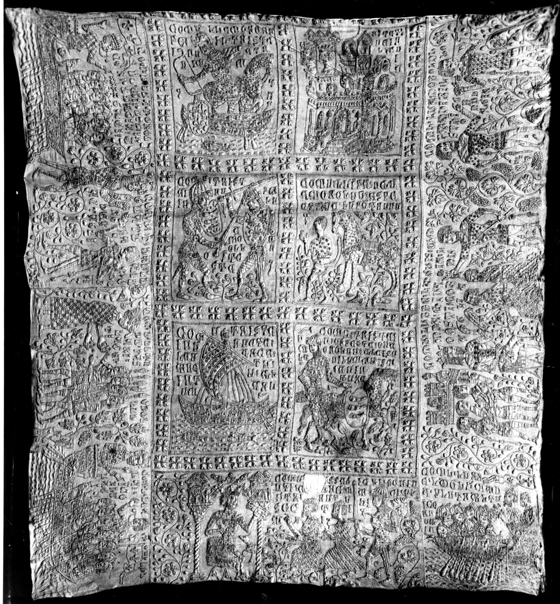

The scarcity of surviving medieval quilts confounds our understanding of what they looked like. Only the two Tristan quilts survive as examples. Inventories that cite motifs of animal figures, heraldic arms, or the legends of Alexander and Solomon provide scant information as to pattern composition or how figures were depicted - full frontal, in profile, in action or formal repose. Opportunely, an embroidered white textile filled with figurative motifs recently re-surfaced in Reims, France, that may add to our understanding of medieval quilt characteristics ( fig.10 ). In 1882, three amateur archeologists stumbled upon a cache of decorative textiles in storage in a convent hospital, located in the former Abbey of Saint Remi. In their published descriptions and drawings of the find, they improbably attributed one piece to the thirteenth century.38 The textiles slipped back into convent storage until mid-2009 when two sisters of the order delivered seven embroidered covers to the Museum of Saint Remi, fittingly located in the same former abbey.

The alleged medieval work is a large cover (100 × 69 inches), fashioned of two layers of white linen, embroidered with blue linen thread in laid and couching stitches. Running stitches in white linen thread fill background areas in the borders. Two side borders are missing. Although the imagery stitched in the presumed early piece is consistent with a medieval origin, the textiles from which it is made belie a later date. The embroidery’s top linen loom width measures about 40 inches from selvage to selvage, an unlikely span for that time. Linen loom width in the later Tristan quilts measures no more than 30 inches. Despite this, and the fact the piece is not technically a quilt because there is no filling between the layers, the piece is worthy of study.

Imagery in the embroidery hearkens to figures and ornamentation witnessed in other medieval decorative arts such as architectural elements, manuscript illustrations, tile pavements, and textile furnishings. A wide border on the long side depicts vignettes set within trefoil arcades and showing figures engaged in agricultural activities similar to the calendar images seen in the Otranto cathedral pavement. Figures engaged in similar work within similar arcades appear on thirteenth-century church exteriors in nearby Rampillon and Amiens. The falconer image on the long border is depicted in identical position on two thirteenth-century seals.39 The short border portrays a hunt in cartoon-like sequence: a wounded doe pursued by three dogs and a hunter, imagery analogous to that in thirteenth-century French mold (fig. 11).40

Motifs under the vignettes and in the body of the quilt show other images comparable to those in the Otranto pavement - a goat, an owl, and that naughty two-tailed mermaid, who appears in close proximity to a startling creature with a head, two legs and a pendulous penis. Fantastic creatures, similar to those depicted on English tiles of the thirteenth- and early fourteenth-centuries, appear as well - a bearded head on legs, the head of a man on the body of a bird, and a double-headed eagle.41 A hunter holding a dog on leash while blowing his horn, fabulous birds, fleurs de lys, and small geometric motifs echo images on contemporary tiles (fig. 12) excavated from the former abbey and traced to a tile factory less than fifteen miles away.

The imagery in the work, drawn from biblical stories, fables and myths, is an affirmation of the medieval ethos. The cock, fish, eagles, harpies, and lions avow Christian faith and redemption. The labourers represent those among the redeemed. The fleur de lys verify the royal patronage of the Reims bishopric. Even the erotic motifs, the mermaid and the creature with exposed genitalia, are of religious significance. Medieval manuscript expert Alixe Bovey writes, ‘viewers might have laughed at grotesques, but far from promoting the kinds of sexualized and corporeal monstrosity they portray, these… images might well have served to condemn it with ridicule’.42

Although this image study supports a medieval origin of the embroidery, it far from proves it. In fact, the Reims Sisters of Augustine seem to have been adept copiers. The date ‘1623’ appears in an embroidered work that was illustrated in the 1882 account. The principal image in this piece is identical to an altar painting present at the coronation of Louis XIII at Reims Cathedral in 1610.43 Other donated embroideries hold similar dates, but the materials they are made from were manufactured at least a century later. They are more likely copies of earlier pieces. Moreover, there is an explanation of why this would be so. Sixteenth-century documents reveal that convent nuns attracted visitors to their cloister by festooning it with imitations of medieval textiles during the annual feast of Corpus Christi.44 To maintain this tradition they were required to replace pieces that became tattered. One can imagine the convent hospital sisters, after nursing their patients, busying themselves with embroideries to hang in the cloister, copying images from their surroundings and recreating older, worn pieces.

Thus, the alleged oldest embroidery could be a copy of a medieval work which conceivably could have been a quilt. It may well be a facsimile of what medieval quilts looked like, showing beasts, compasses and rosettes, just as described in Charles V’s fourteenth-century inventory. The format of the piece, showing orderly organization of repeated motifs in the centre, framed by a sequence of borders, is consistent with those found in bedcovers. It is pleasant to consider the possibility of it being commissioned for the 1364 coronation of Charles in Reims Cathedral, perhaps to decorate royal lodgings. The profusion of fleur de lys in the embroidery suggests the original piece predated the king’s 1376 decree limiting ornamentation to only three lilies, in honor of the Holy Trinity. Indeed, Charles V’s 1380 estate lists six white ‘courtepointes’.

Animals and octagons

One more surviving piece may provide insight into the look of medieval quilts. A white quilted and corded work coverlet in the V&A shows an overall mosaic pattern of octagons and diamonds, each holding a fantastic bird or beast. Lamentably, these figures are difficult to make out. Apparently, the original filling was removed at some point leaving only remnants of twisted cotton in corners. Consequently, figures that were once raised in legible relief are now flat, most of them decipherable only in sketches (fig. 13 ).This quilt is made of two layers of linen, the bottom layer loosely woven, worked in back and running stitches with white linen thread. The geometrical figures are delineated by two rows of two-ply cotton cording. Figures within octagons are also enclosed by eight-point stars with four-lobed leaf forms outside the angles of each star point. The piece has been cut down from its original size to 198.1 cm × 111.8 cm.

The origins of this quilted coverlet are elusive. Despite museum catalogue notes that identify the piece as being sixteenth century, German, the only traceable connection to Germany is its purchase from a Strasburg dealer, while the date of production could be earlier according to two textile historians.45 A late 1300s manuscript from Genoa shows comparable composition and imagery. In the manuscript orderly roundels enclose standing eagles, their wings wide-spread, and lions standing in profile, tails high and claws flared, analogous to the creatures depicted in the bedcover.46 These fantastic creatures also relate to heraldic and religious imagery of eagles and lions seen in thirteenth- to fourteenth- century tiles and a variety of woven and embroidered European textiles that date from the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries. In particular, the birds and beasts echo those seen in ‘intarsia’ or inlaid patchwork church textiles found in Finland, Germany and Sweden (fig. 14) (fig. 15).47 The motifs depicted in the quilt were used over too wide a geographical range and too long a time to anchor its origin. The all over pattern suggests the piece was made as a bedcover. But the imagery may have been problematic. If it was heraldic or religious in intent, perhaps the filling was removed to lessen its importance in a time of political or religious disruptions. Or perhaps troubled dreams came from sleeping in proximity to these clawed, fanged and winged creatures.

Summary: Legend and myth as expressed in white quilted works

All-white corded and quilted medieval textiles were infused with the same imagery that was portrayed in all the medieval decorative arts, reflecting the religious faith, self-identity, social ideals, and status of their owners. Surviving textiles and written records consistently associate French Normans and members of the House of Anjou with these quilted pieces. This suggests that the political success of the Normans and Angevins may have been accompanied by a conquest of artistic imagination, contributing to the development of a rich tradition of decorative all-white corded and quilted textiles in southern Italy and in France. A similar investigation of inventories, documents and surviving decorative arts in other parts of medieval Europe would add to understanding of the extent of this practice.48

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Marc Bouxin, Conservateur en chef du Patrimoine, Direction de la Culture, Ville de Reims; Clare Browne, Curator, Textiles; Furniture, Textiles and Fashion Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; and Susanna Conti, Conservatore Direttore, Opificio dell Pietre Dure e Lab di Restauro, Florence, Italy; all of whom gave me access to rare works and their professional insights.

Endnotes

-

Anonymous. ‘Le Lai del Desire’, [Sur un bon lit s’ert apulé | La coilte fu a eschekers | De deus pailles ben fais e chers]. In Michel, Francisque. Lais inédits des XIIe et XIIIe siècles. Paris, 1836: 18–19. Accessed 15 July 2009. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k72330n ↩︎

-

The French word ‘tapisserie’ refers to a hanging, whether woven, embroidered or quilted. ↩︎

-

Bloch, R. Howard. A Needle in the Right Hand of God. New York, 2006: XI, 87. ↩︎

-

Bloch, R. Howard. A Needle in the Right Hand of God. New York, 2006: 18. ↩︎

-

Gianfreda, Grazio. Il Mosaico di Otranto. Lecce, Italy, 2002. ↩︎

-

Loomis, Roger Sherman. ‘Vestiges of Tristram in London’. The Burlington Magazine 59. Accessed 11 July 2009. https://www.archive.org/stream/burlingtonmagazi41londuoft/burlingtonmagazi41londuoft_djvu.txt ↩︎

-

Randles, Sarah. ‘The Guicciardini Quilts’. Medieval Clothing and Textiles, vol.5. Woodbridge, UK, 2009: 106–108. This chapter of Tristan lore precedes his memorable romance with Mark’s wife Isolde. ↩︎

-

Randles, Sarah. ‘The Guicciardini Quilts’. Medieval Clothing and Textiles, vol.5. Woodbridge, UK, 2009: 99, 107. ‘Recent laboratory analysis of the V&A quilt…confirms that the stuffing is in fact cotton fibre’. Tristan quilt dimensions are: V&A 320 × 287 cm; Bargello 247 × 207 cm. Accessed 15 July 2009. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/objectid/O98183 ↩︎

-

de Joinville, Jean. Histoire de S. Louis, IX du nom, roi de France. Paris, 1668: 79. Accessed 14 July 2009. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5575244j ↩︎

-

Randles, Sarah. ‘The Guicciardini Quilts’. Medieval Clothing and Textiles, vol.5. Woodbridge, UK, 2009: 93. The third fragment, the Pianetti or Azzolini quilt, is in private hands. Randles states it may come from the same atelier as the museum pieces. Motifs show a central medallion with images of Tristan and Isolde on a field of fleur de lys. ↩︎

-

Il Decamerone. III: 145. Accessed 16 August 2009. https://books.google.com/books?id=mOARAAAAIAAJ ↩︎

-

Polo, Marco. The Travels of Marco Polo. I, Ch.3. Accessed 7 August 2009. https://reactor-core.org/marcopolo.html ↩︎

-

Oeuvres complètes de Eustache Deschamps. IX: 44, lines 1252–54. Accessed 18 August 2009. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k51349 ↩︎

-

Fennell Mazzaoui, Maureen. The Italian Cotton Industry in the Later Middle Ages, 1100–1600. Cambridge, 1981: 23. ↩︎

-

Fennell Mazzaoui, Maureen. The Italian Cotton Industry in the Later Middle Ages, 1100–1600. Cambridge, 1981: 26 and Havard. Dictionnaire. I: 947. Courtepointe, coulte pointe, courtes-pointe and other variants will be used as they appear in original texts. ↩︎

-

Randles, Sarah. ‘The Guicciardini Quilts’. Medieval Clothing and Textiles, vol.5. Woodbridge, UK, 2009: 103–127. ↩︎

-

Archives de Marseille. 13 January 1297, cited in G. d’Agnel, Arnaud. L’Ameublement Provençal et Comtadin durant le Moyen Age et la Renaissance. Marseille, 1929: I, 113. ↩︎

-

Havard. Dictionnaire. IV: 1505; d’Agnel, Arnaud. L’Ameublement Provençal et Comtadin durant le Moyen Age et la Renaissance. Marseille, 1929: 123 ↩︎

-

Douët-d’Arcq, Louis. Nouveau recueil de comptes de l’argenterie des rois de France. Paris,1874: 76, 103. Accessed 22 August 2009. https://www.archive.org/details/nouveaurecueilde00doue ↩︎

-

Havard. Dictionnaire. III: 707. ↩︎

-

Havard. Dictionnaire. I: 375; II: 1070; IV: 435, 878. ↩︎

-

d’Agnel, Arnaud. L’Ameublement Provençal et Comtadin durant le Moyen Age et la Renaissance. Marseille, 1929: 221. ↩︎

-

Savary des Bruslons, Jacques. Dictionnaire universel de commerce. Paris, 1723: I, 432. ↩︎

-

Havard. Dictionnaire. IV: 1238; I: 382; II: 1237. ↩︎

-

Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence; interview with conservators 10 November 2008 ↩︎

-

Sherman Loomis, Roger and Laura Hibbard Loomis. Arthurian Legends in Medieval Art. London, 1938: 62. ↩︎

-

Thornton, Peter. The Italian Renaissance Interior 1400–1600. London, 1991: 48, citing Decameron VII and IX: 73. ↩︎

-

Havard. Dictionnaire. III: 151. ↩︎

-

Havard. Dictionnaire. II: 846 and 1238; III: 1005. ↩︎

-

Battuta, Ibn. Voyages. III (1334). Paris, 1997: 108; cited in Alexandre Fiette, ‘Matelassage et habillement en Occident’. L’étoffe du relief. Geneva, 2006: 27–28. ↩︎

-

Havard. Dictionnaire. I: 249, 316; III: 1036. ↩︎

-

Havard. Dictionnaire. II: 882. ↩︎

-

Société de l’histoire de l’art français, Archives de l’art français. Paris, 1851–66, II: 305–6. Accessed 17 July 2009. ↩︎

-

Barthélemy, Louis. ‘Inventaire du château des Baux en 1426’. Revue des Sociétés savantes. 6 série, VI, 1877. Paris, 1878: 39. ↩︎

-

d’Agnel, Arnaud. L’Ameublement Provençal et Comtadin durant le Moyen Age et la Renaissance. Marseille, 1929: 150. ↩︎

-

Havard. Dictionnaire. III: 747. ↩︎

-

Beaumelle, Marie-José. ‘Les étoffes’. Les arts décoratifs en Provence du XVIIe au XIXe siècle. Aix-en-Provence, 1993: 103; interview 29 March, 1994. The quilt was sold at auction in 1960; its present status is unknown. ↩︎

-

Givelet, Charles-Prosper. Les toiles brodées, anciennes mantes ou courte-pointes conservées a l’Hôtel-Dieu de Reims. Reims, 1883. ↩︎

-

Piton, Camille. Le costume civil en France du XIIIe au XIXe siècle. Paris, 1926: 15–16, 24–25. ↩︎

-

Paris, musée national du Moyen Âge, Thermes de Cluny, inv# CL17723 ↩︎

-

Eames, Elizabeth. Medieval Craftsmen: English Tilers. London, 2004: figs 43–44, 47, 49, 62, 65, 67. ↩︎

-

Monsters & Grotesques in Medieval Manuscripts. London, 2002: 43. ↩︎

-

Engraving, ‘Sacre de Louis XIII à Reims le 17 octobre 1610’, Chateaux of Versailles and the Trianon, invgravures 718 ↩︎

-

Havard. Dictionnaire. IV: 211. ↩︎

-

Clare Brown, V&A textile curator, says nothing precludes an earlier date, interview 23 July 2009. Staniland, Kay. Embroiderers. London, 2002: 40, dates the work to the fifteenth century. ↩︎

-

Cocharelli. Treatise on the Vices. The British Library, Add. Ms.27695, fol. 3v, illustrated in Morrison, Elizabeth. Beasts, Factual and Fantastic. Los Angeles, 2007: 54. ↩︎

-

Eames. Tilers, figs 38, 44; Regensburg weave, V&A inv#613-1891; Staniland, Kay. Embroiderers. London, 2002: figs 27, 30, 35; Inlaid Patchwork in Europe from 1500 to the Present. Berlin, 2009: catalogue nos.D21, FIN01, FIN02, NL01, S03, S05, S06. ↩︎

-

Further study of the tradition of white corded and quilted needlework will be found in the monograph Marseille, published by the International Quilt Study Center, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, in the fall of October 2010. It will accompany the exhibition ‘Marseille’ held at the International Quilt Study Center & Museum in Lincoln from 13 November 2010 to 8 May 2011; www.quiltstudy.org ↩︎