Abstract

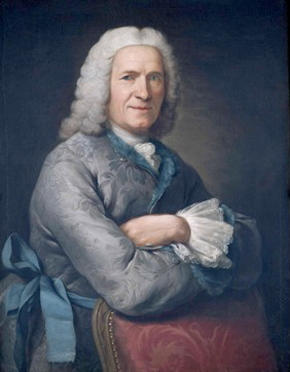

Jean Revel (1684–1751), the ‘Raphael of silk design’, had his portrait painted in 1747 in Lyon. This article focuses on the dress and furniture in this portrait, investigating the message the artist and the sitter conveyed consciously or inadvertently.

Introduction

In 2014, the V&A will open newly refurbished galleries devoted to design and art made and used in seventeenth and eighteenth-century Europe. The exhibits are among the most glamorous and luxurious in the Museum’s collections, far removed from the experience of most twenty-first century museum visitors’ everyday lives. The gallery team’s ambition is to make them physically and intellectually accessible to many audiences. One method of doing so is to offer insights into the lives of those who knew these objects intimately, whether as makers or consumers. Among the exhibits will be some of the finest fashionable silks manufactured in the highly regarded and much copied French silk manufacturing centre of Lyon in south-east France. Designers and makers from that city were acknowledged trendsetters from the late seventeenth century onwards and are credited with establishing the seasonal fashion cycle in dress which continued into the late twentieth century.1

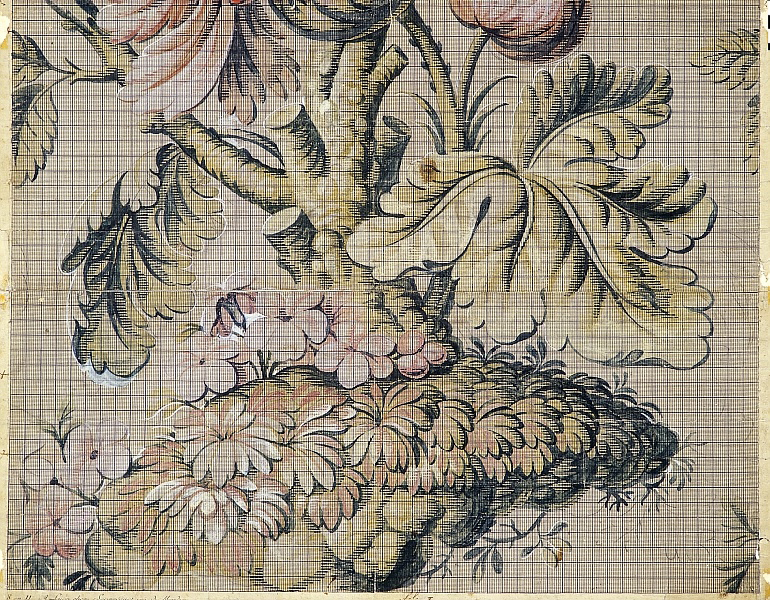

The V&A has collected French eighteenth-century silks since the Museum was founded in the second half of the nineteenth century because of their aesthetic and technical excellence. Between the 1950s and 1990s, two eminent curators of textiles, Peter Thornton and Natalie Rothstein, devoted much time and energy not only to collecting European silks and silk designs that complemented those already in the Museum, but also to delving deeper into the context from which these silks originated – the methods by which they were designed and woven, the places in which they were made, the people involved in their manufacture, and the consumers who acquired them, either for dress or for furnishings.2 In the course of research for his pioneering monograph Baroque and Rococo Silks (1965), Peter Thornton, then Assistant Keeper of Textiles, sought ‘to trace the general development of the patterns which appeared on the richer classes of silk material’ between 1640 and 1770.3 The V&A’s collections acted as a starting point for his research which then extended to many archives and museums in Europe, and provided a chronology that, with minor modifications, is still widely used today. During his research, Thornton’s curiosity was piqued by the silk designer Jean Revel (1684–1751), partly because his was one of the few names that could be attached to surviving designs, notably a signed and dated technical drawing (mise-en-carte) in the Musée des Tissus in Lyon (fig. 1), two annotated freehand designs in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, and an anonymous set of French freehand designs in the same style in Prints and Drawings at the V&A (fig. 2).

Thornton was also well aware of a panel of silk which he reattributed to Revel (fig. 3), chose for the dust jacket of his book, and subsequently exhibited in the 1970s in the galleries currently being refurbished. He chose to follow up all the relevant primary sources then available for Revel, and published a seminal article on the designer in 1960.4 His, and more recent, research on the naturalistic silks created by Revel and his contemporaries reveals that the many variations on luxuriant foliage in surviving designs and fabric were used in both women’s and men’s dress in the 1730s and beyond.5 Some of these silks were made into nightgowns, which were depicted on the backs of nobles at home and abroad (figs 4 and 5). Moreoever, these silks were accessible from prestigious retailers in major cities, and many of them would have been within the financial reach of silk merchants and manufacturers. These men presumably had privileged access as they provided the raw materials and designs for the silks, commissioned their weaving up, and inspected the end products when they came off the looms in Lyon, before dispatching them to retailers, who added a considerable mark-up to the price.

Intriguingly, in the only known portrait of Revel (fig. 6), the designer wears a fabric that, although it is patterned, is a far cry from his own elaborate designs. This portrait was painted some years after these particular silk patterns were the height of fashion. Nonetheless, brocaded highly patterned silks were still in vogue. Revel’s decision to wear something simpler, therefore, begs the question, why? Does his choice tell viewers something about the taste and attitudes of men of his means, station and age, and thus more broadly about the patterns of consumption of the mercantile bourgeoisie and the meanings they attached to the highly decorated silks they created? Through a rigorous analysis of the dress and furniture in this portrait, this article begins to address the wider context for the consumption of brocaded silks, and the difference between aristocratic opulence and bourgeois respectability. This analysis aims to help twenty-first century viewers to understand the man behind the designs – and the circles in which he moved. It is dependent not only on methodical analysis, but also on new documentary evidence, found and published in the 1980s and 1990s.6

Portrait, sitter and portraitist

For many generations, historians have described Revel as an artist who achieved great success and wealth through the application of his painterly skills to silk design.7 By the time of his death in 1751 he was certainly a well-heeled Lyonnais bourgeois.8 Within six years he had been hailed the ‘Raphael of silk design’ and commended as a role model for his successors in the trade.9 Revel commissioned this portrait around 1747 at the age of 63, choosing the Royal Academician Donat Nonotte (1708–85), as his portraitist. The half-length oil painting, signed and dated 1748, represents an alert elderly man in fine linen shirt, floral patterned nightgown and shoulder-length grey wig, standing behind a carved walnut Louis XV chair, his crossed arms resting on the frame. Only three years later, on Revel’s death, the painting passed to his principal heir (héritier universel), his second daughter Jeanne-Barbe Revel (1713–85), wife of Jean-François Clavière (d. 1789), a wealthy merchant manufacturer who rose to the status of city magistrate.10 It remained in the family until about 100 years later when it was donated to the Musée d’Art et d’Industrie in Lyon. Today it hangs in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Lyon in its original impressive gilded frame.11 Fortuitously, the inventory of Revel’s possessions taken at his death includes a description of the clothing and furniture he owned just three years after the portrait was painted. It is therefore possible to consider the portrait against this surviving documentary evidence in order to set it in a broader cultural context of sitter and portraitist.

Evidence for Revel’s work as a painter is still frustratingly elusive. There is no doubt however that he had knowledge of and contacts in the trade through his father, the history painter Gabriel Revel (d. 1712). He subsequently became deeply involved in the silk manufacturing community although he never apparently became a member of the silk weaving guild.12 An immigrant to Lyon, he arrived around 1710 aged 26, and by 1720 was already gainfully employed as a merchant. In 1747, when Revel commissioned this portrait, he was widowed, with four daughters, to each of whom he had given an impressive dowry of 33,000 livres between 1738 and 1746. At this time, in Lyon, only about 4.55% of marriage settlements exceeded 10,000 livres.13 In 1742 he had purchased property in the country (a sign of gentrification in eighteenth-century Lyon),and in the wake of his wife’s death in 1746, he and his son-in-law had bought a house in the prestigious rue Sainte Catherine in the main business quarter of the city.14 He also owned a share of a house in Paris from which he earned rent.15 When Revel was dying he dictated his will, which is the only written testimony of his way of thinking. It followed the impersonal conventions of such legal documents, revealing little of the man other than his stated religious faith, his involvement in a local confraternity, and his relationship with his close-knit family who were his only legatees apart from his seven servants. He expressed no particular attachment to his belongings. There was nothing progressive or exceptional in his stated intentions, any more than there was in the living spaces that emerge from the inventory taken after his death.16

Revel lived well. His surroundings were spacious and comfortably appointed; none of the furnishings was brand new; many were possibly a little old-fashioned, in so far as may be deciphered from an inventory. He had four rooms and a closet to himself, including the kitchen where his housekeeper slept. Most of his furniture was made of limewood or walnut, the latter a wood commonly used in the south of France, well-suited to carved ornament and with an attractive grain.17 Made of wool, his upholstery fabrics and hangings were needlework on canvas, tapestry, green goffered plush and brown serge. His green plush chairs did, however, have printed calico (cotton) case covers.18 Many paintings and several mirrors, all with gilded frames adorned his walls in town and country, he had a small number of silver dishes and cutlery as well as crockery, about a hundred books on history and religion, games tables and games, and two valuable musical instruments. Indeed, the objects with which he surrounded himself were those of a Lyonnais bourgeois – good quality, hard-wearing, not necessarily the height of fashion.19 The only way in which he differed from most bourgeois was in the sheer number of paintings he owned, some 75 in total (23 in town and 52 in the country).20 This scale of ownership was consistent with that of artists, and a little lower than that of dedicated (and wealthy) collectors.

Revel may have inherited some of these paintings; he may have painted or acquired others; he evidently commissioned the portrait under discussion here. His choice of Donat Nonnotte was discerning on a number of levels. As Sylvie Martin has noted, both men were artists so already had something in common.21 However, the parallels in their experience ran deeper, for Revel, originally from Dijon, an immigrant to Lyon, still had good connections with Paris, and had adapted his skills in painting to make a good living. Nonnotte, peintre du roi since 1741, resident in Paris for ten years, had been born and bred in Besançon, and was to adopt Lyon as his home definitively in 1750. He, too, had adapted his professional expectations, shifting from an emphasis on history painting to portraiture. The change was well judged for, like Revel, he was to make a very respectable career for himself and to die amid bourgeois trappings.22 Shared experience, ambition, and pragmatism apart, Nonnotte was already known in Lyon by 1747 when he painted Revel. He had portrayed some of Lyon’s élite both in Paris and during previous long sojourns in Lyon – of seven months in 1745 and 1746 and 22 months between 1746 and 1747. Clearly, he had begun to build up the client base that was to serve him for the rest of his life and was to have an impact on the nature of his output. It comprised the commercial bourgeoisie or business elite, as well as the city magistracy, who were happy with far simpler (and cheaper) compositions than some of Nonnotte’s previous more affluent aristocratic clients in Paris.The latter were often complemented by complex compositional backgrounds and foregrounds, whereas the former stood out against plain grounds, uncluttered by props.23

Thus, in 1748 when Nonnotte completed Revel’s portrait, he was at the start of his career as a portraitist, already had excellent credentials, and may have been contemplating moving to Lyon. He was developing his ideas on his chosen genre. By 1754 he had become a member of the Académie de Lyon, by 1756 the first director of the Ecole Gratuite de Dessin, a school intended to train designers, and by 1762 the city’s official painter. Later, in 1772, he was to express his views on portraiture in his sixth discourse to the Académie de Lyon thus, ‘Portraits… serve to preserve and express sentiments of respect, esteem, friendship and love. It would be a mistake to believe that the likeness of the features was the only merit of a portrait’.24 If such sentiments suited Revel’s intent, then surely his dress and pose were likely to have been consistent with the respect and esteem appropriate to his age and status, just as the framing of the portrait was in keeping with his interior decoration. Whether he wished to announce his artistic leanings is another matter.

Revel’s pivotal role in silk design has ensured that this painting appears in most articles written on him since the mid-twentieth century, in the scarce literature on the portraitist Donat Nonnotte, and in some publications on famous Lyonnais. When not used purely as a likeness of the sitter, it has been discussed in art historical terms as a fine example of the artist’s style and accomplishment. The dress and chair, as well as the facial expression, have merited comment because Nonnotte reveals a penchant for, and sensitivity in, the realistic representation of textiles. Moreover, in this particular case, there are no other props, the background being shades of black and grey. As early as 1915, Félix Desvernay identified Revel relatively uncontentiously as, ‘bewigged, dressed in a lined nightgown, in grey silk, with large motifs, he looks out at the spectator with a smile and stands with his arms crossed on the back of a red chair’.25 More daringly, seventy years later, in the only serious catalogue of Nonnotte’s work to date, Sylvie Martin drew attention to the way in which the clothing might reflect the sitter’s reputation or act as an attribute. She focused on the textiles because of Revel’s reputation as a painter/designer of flowers, noting:

‘[Revel is] dressed in a lined and grey brocaded nightgown, encircled by a blue sash. He looks at the spectator smiling and has his arms crossed on the back of a red chair… Everything in this picture recalls the activities of the painter [Revel]: first, his brocaded nightgown with its floral motifs to which he was particularly attached, then the upholstery of the chair which presents a similar decoration to the painter’s nightgown.’26

This attempt to read the dress in the context of the sitter’s predilections is welcome, yet leaves fertile territory for exploration by cultural and social historians with a firm grasp of textiles, dress and furniture. Revel is, indeed, wearing a nightgown with a stylised floral pattern, but it is not made of brocaded silk, a particularly luxurious, often polychrome, textile for which Revel designed and which Nonnotte depicted with bravado elsewhere.27 Instead, what is shown is a grey fabric with a monochrome pattern, possibly silk, wool or worsted damask.28 The nightgown’s lining is made of a blue fabric with long pile, while its sash, of the same shade of blue, seems to be silk taffeta. The shirt worn beneath the nightgown is worthy of attention, too, for Nonnotte has taken care to demonstrate the fineness of its linen and the delicacy of the whitework embroidery with which its neck and cuffs are edged. The style of textile patterns, cut of garment, form and materials of the chair are all pieces of the jigsaw puzzle that give the portrait meaning. Each individual element and the way in which the elements are combined, need to be fitted together methodically in order to reach a nuanced interpretation of what the artist and sitter conveyed. First, are the clothes and furniture real? Did they belong to the sitter or to the artist, or were they imagined, or even borrowed from another visual source such as an engraving? How do they relate to the rest of this particular artist’s oeuvre, to conventions in contemporary and historic artistic production, and to the etiquette, performance and dissemination of contemporary fashion? To some extent, the answers may be found by relating the depiction to objects, images and texts of the period.29

On clothes and chairs

Revel’s clothing, as recorded in his inventory, was that of an older man of a certain status (tables 1 & 2). Everything with the exception of one full ensemble was worn or old or imperfect, but nothing was absolutely worn out or turned.30 The name of the main outer garment (justaucorps or close coat) denoted a fashion most readily associated with the late seventeenth and the early eighteenth century.31 The textiles were good and durable quality, wool dominating for his suits, some silk evident for more prestigious occasions, the finest Holland trimmed in muslin (mousseline) for his good shirts.32 The dominant colours were the black and grey typical of the sombre palette of the first half of the eighteenth century. Indeed, red and blue were the only other colours present. Notable was a substantial amount of linen, whether shirts or handkerchiefs, and a good supply of stockings of different qualities (silk, wool and linen). If this were the wardrobe that represented his life - and, of course, it does not account for clothing worn out, given away, or filched before the inventory was taken - then Revel had acquired a suit at least once every five years since his majority and two shirts every year. Of ten formal coats (justaucorps), three were made of silk, of his 11 pairs of breeches, three were made of silk velvet and three of the ribbed silkgros de tours, and of his nine waistcoats, seven were of silk. He also owned 23 pairs of stockings, 31 nightcaps, two pairs of boots, five hats, and 26 handkerchiefs. His eight coats probably represented suits which had originally had two or three pieces. The likelihood is that Revel had owned in his life other suits that had been worn out. The total value of his clothes, all of which were used, was low at 235 livres 10 sols, approximately the cost of two to three new cloth suits.33 Regardless, his outer garments represented about double what a master weaver might have amassed in a 40-year life span. At that point, a Lyonnais master weaver’s wardrobe was calculated at a coat every eight years, work clothes every four years, a hat every three, a shirt and handkerchief, a pair of stockings, a cap, and a pair of shoes every year.34 While the weaver’s coat may have been fashionably cut, his work clothes were very different from the garments in Revel’s wardrobe. Revel’s accessories, too, were suitable to a bourgeois appearance and to observing social etiquette: two old wigs, four hats, a pair of silver buckles for his shoes, a silver watch, and a cane with a gold knob. In town, he kept all his finest pieces and those required for formal occasions. He still had enough in the country to cut a fine figure, albeit most of his underwear was in rougher cloth. In his clothing, as in his living space, then, Revel revealed his interest in good quality, respectability being the keynote rather than flamboyance. He owned no courtly lace, brocade, nor extravagant jewellery.

Table 1: Clothing kept in town**

(Source: ADR BP2187: Inventory, 14 December 1751)

Where items had matching counterparts, these are noted in the third column (hence the disparity in numbers)

| Garment | Total | Disposition and fabrics |

|---|---|---|

| Boots (bottes) | 1 | |

| Breeches (culottes) | 4 | 1 in grey cloth (drap) – see under coat, waistcoat and nightgown |

| Buckles (boucles) | 1 | 1 pair in silver |

| Cane/walking stick (cane) | 1 | 1 with gold knob |

| Coat (justaucorps) | 3 |

1 with matching waistcoat of Belleville cloth with

copper buttons 1 of black cloth 1 with two pairs of matching breeches in black gros de tour (i.e. silk) |

| Handkerchiefs (mouchoirs) | 38 | 35 (colour) + 3 (white) cotton and linen |

| Hats (chapeaux) | 4 | 4 of poil (i.e. with nap, velvety) |

| Muff (manchon) | 1 | 1 of fur |

| Neckcloths (cols) | 20 | 20 muslin (mousseline) |

| Nightcaps (bonnettes) | 7 | 7 finest linen, Holland (hollande) |

| Nightgowns (robes de chambre) | 2 |

1 with matching waistcoat and breeches of callimanco

lined in swanskin (calemande et moleton) 1 of satin |

| Shirts (chemises) | 23 |

20 Holland trimmed in muslin (hollande garnie en

mousseline) 3 homespun cloth (toile de menage) |

| Shoes (souliers) | 0 | |

| Stockings (bas) | 16 | 8 silk 2 wool 6 linen |

| Waistcoats (vestes) | 5 |

1 with matching breeches of patterned velvet (velours

cizelé) 1 of plain velvet (velours uni) 1 of blue gros de tour trimmed with a little gold braid |

| Watch (montre) | 1 | 1 silver |

| Wigs (perruques) | 2 | 2 |

Translations into contemporary English: Chambaud, Louis. Nouveau dictionnaire françois-anglois & anglois-françois: contenant la signification des mots, avec leur différens usages, les constructions, idioms, façons de parler particulières, & les proverbes usités dans l’une et l’autre langue, les termes des sciences, des arts, & des métiers, le tout receuilli des meilleurs auteurs anglois & françois. London: John Perrin, 1778.

Table 2: Clothing kept in the country

(Source: ADR BP2187: Inventory, 14 December 1751)

Where items had matching counterparts, these are noted in the third column (hence the disparity in numbers)

| Garment | Number | Disposition and fabrics |

|---|---|---|

| Boots | 0 | |

| Breeches | 2 | 2 velvet |

| Coat | 5 |

1 grey camblet (camelot) with gold buttons with

matching breeches 1 grey broadcloth (drap gris) 1 black camblet 1 grey silkdrugget (droguet de soie) 1 red cloth (drap) |

| Handkerchiefs | 4 | 4 cotton (toile cotton) |

| Hat | 1 | 1 beaver edged with an old gold braid |

| Neckcloths | 49 | 49 muslin |

| Nightcaps | 24 | 24 linen from Rouen (toile de Rouen) |

| Nightgowns | 2 | 1 flannel (flannelle) 1 callimanco |

| Shirts | 60 |

17 holland trimmed with muslin 1 homespun cloth 42 linen (from Troyes) and holland trimmed with muslin |

| Shoes | 0 | |

| Spatterdashes (guêtres) | 1 | 1 wool |

| Stockings | 9 | 4 linen 5 silk (different colours) |

| Under waistcoat (camisole) | 1 | 1 material not specified |

| Waistcoats | 2 | 2 silk (étoffe de soie) |

| Wigs | 0 |

For a half-length portrait that obscured his body from the waist down, Revel could therefore have chosen a formal coat and waistcoat to wear with his fine linen, or a nightgown – unless he opted for something in the realms of fantasy. He chose a nightgown. Nonnotte represented its textile design exceedingly carefully, so contemporary viewers would have understood that its wearer paid attention to fashion – the types of motif and their disposition were new in the 1740s.35 The nightgown fits Revel’s body snuggly. Tied in place with a sash, its buttons at the neck and at the end of the sleeves suggest further methods of fastening. It reveals a well laundered linen with its whitework embroidery. While the ‘light-touch’ of this embroidery looks forward to the 1750s, it may well also represent a more sparing bourgeois investment, a simpler version of the exquisitely complex pieces that survive in museum collections today.36 The wig that finishes off Revel’s rig-out is formal and conservative, its style having been fashionable in the 1720s. By the 1740s, the bag wig had become popular among fashionable men whose hairdressers dressed them in short curls above the ear, pulling the length back into a queue which was often kept in a black silk bag – similar to the style worn by Nonnotte in his self portrait (fig. 9).37 Overall, then, Revel’s attire speaks of an aging man of means rather than an extravagant young fop.

All of this dress could have belonged to Revel and relates to items in his inventory. His two wigs were deemed ‘old’, an adjective that may refer to style as much as to wear and tear.38 All of his best shirts were made of holland and trimmed in muslin, and he owned four nightgowns, three warm woollen ones and one of satin (presumably silk). The callimanco (calemande) nightgown he kept in town, with its matching waistcoat lined in swanskin (molleton) and breeches made of swanskin, seems to be a likely contender as a match for the one depicted in the portrait – although the colour is not specified in the inventory and the hairiness of the surface may be too great.39 This ensemble was the only one valued separately from other garments and at the relatively high sum of 20 livres (one tenth of the total value of his wardrobe), and it was the only one not described as old or worn.40 While this identification is not definitive, what is important is the fact that portrait and wardrobe echo each other convincingly.

The chair falls into a similar category, since its wood fits with what Revel favoured for his two smaller rooms in town. One boasted six walnut chairs, a matching armchair and stool, the other twelve armchairs, their stool being in another, possibly larger, room (table 3). The colour of the upholstery of the chair in the portrait is, however, at odds with his actual possessions, being red rather than green, possibly worsted or silk damask or goffered velvet for upholstery, but definitely not needlepoint or calico. Red and green were the two colours most favoured for interiors in the first half of the century in Paris, red being the more expensive dye and largely restricted to royal interiors after about 1715.41 The form of the chair was so up-to-date that it most likely belonged to a Parisian household or to a Lyonnais one with close links with Paris. Its carved frame and brass nailing, indicative of fine craftsmanship, bear a marked similarity to the chair in Nonnotte’s later self-portrait (fig. 9). It is very similar to known examples of the work of Pierre Nogaret (1720–71), the best known of Lyonnais cabinet-makers who had arrived in Lyon from Paris in 1744. He became a master craftsman there in 1745, around the time Nonnotte visited the city.42 Artists, of course, had chairs as props (as well as nightgowns), just as photographers did at a later date, so perhaps this one belonged to Nonnotte. He may have chosen to colour his upholstery to harmonise with the overall palette in his paintings.43 In some respects, of course, whether the clothing and furniture belonged to the sitter is academic: they are significant because Revel selected them and because they are in the spirit of his actual possessions.

Table 3: Seating in Revel’s town flat, first floor, rue Sainte Catherine

| Room | Type of chair | Number | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kitchen | chaises (chair) | 5 | limewood, covered in rush |

| fauteuil (armchair) | 1 | covered in cloth | |

| Room 1 (chambre) | chaises | 5 | Limewood |

| chaises | 6 | walnut, stuffed with horsehair and covered in needlework | |

| tabouret (stool) | 1 | walnut, stuffed with horsehair and covered in needlework | |

| fauteuil | 1 | walnut, stuffed with horsehair and covered in needlework | |

| Closet off Room 1 | fauteuil prie (prie-dieu) | 1 | covered in moquette |

| Room 2 (chambre) | fauteuils | 12 | walnut, stuffed with horsehair and covered in green goffered plush, with printed cotton case covers |

| Room 3 (salle) | chaises | 6 | limewood, covered in rush |

| tabouret | 1 | walnut, covered in needlework |

Artists, merchants and nightgowns

Did these items allude to Revel’s life in design, or suggest he thought he belonged to a painterly elite? The nightgown merits closest inspection, not just its cut and textile, but also how it is worn and with what. Originally a garment donned in the privacy of the home, a nightgown offered relaxation from the formal structured coat as well as warmth in draughty interiors.44 By the mid-eighteenth century, men wore nightgowns en famille and for welcoming visitors. Some men, including merchants, even decided to be portrayed in a nightgown, perhaps because the intimacy of the garment suited the context in which the portrait was to be hung.45 Nightgowns had, however, also gained currency as a sign of artistic or intellectual leanings. The many portraits presented by artists as their reception pieces as peintre du roi exhibited at the Salon reveal artists’ affection for the voluminous folds that allowed them to emulate classical drapery and show off their skill at painting the sheen of plain and shot silks. Some such gowns were, of course, studio props from the portraitist’s own collection.46 Such was the case with the one worn in Louis-Michel Van Loo’s portrait of the art critic and philosopher Denis Diderot in 1767 (fig. 7).47 Diderot thought the lustrous silk altogether too luxurious, noting it gave him the air of a minister of state rather than a philosopher. In all other respects, the painting shows a lack of concern with the usual social etiquette: no wig is worn and collar and cuffs are very clearly unfastened in a slovenly way.48 Van Loo had represented himself in the same garment in much the same spirit, artistic yet showy (fig. 8). Diderot, however, equated his literary and artistic independence, his domestic and vestimentary comfort, with his old callimanco nightgown, which hugged his body and did not deter him from wiping his ink-stained hands on its folds.49 The different textiles had very clear associations for him, as they, no doubt, did for Revel, a silk manufacturer who owned both silk and callimanco nightgowns. It seems unlikely, however, that Revel would have wiped dirty hands on such a pristine item as the one in the portrait.

Nightgowns are not common in Donat Nonnotte’s oeuvre, a fact which may in itself be an indication of the taste of his Lyonnais bourgeois clients who may have preferred to be represented in more formal attire, which hugged the body more closely than nightgowns did. Nonnote’s own self portrait of 1756 (fig. 9), painted when he had already lived in Lyon for eight years, is reminiscent of the ‘artistic’ drapery of academic portraits. The palette and brush in his hands and the easel in the background underline his identity as an artist. This presentation is quite different from his depiction of Revel, despite their shared heritage, place of residence and choice of garb.50 Nonnotte’s nightgown is a plain silk, apparently lined in a lightweight fabric, a fact emphasized by the excess material draped over the chair. The artist’s body language is open, the nightgown revealing his smart and fashionable beige waistcoat with gold buttons and buttonholes; his cuffs and collar are of lace, not simply embroidered muslin – and his shirt is artfully, rather than carelessly, open at the neck. In contrast, Revel, while apparently at ease, has his gown pulled tightly around him, his waistcoat is concealed, his austere neckcloth tied tight. The fabric design is up-to-date, the demeanour is formal. Perhaps his pose related to where the painting was to be hung, as dress and painting decorated body and wall respectively, but also presented a message to their viewers.51 Knowledge of this portrait’s intended or likely audience is therefore crucial in reaching a rounded understanding of its message.

Revel’s portrait was not for public consumption, in the sense that it was not to be exhibited at the Salon in Paris, and Lyon did not yet have any such public forum for displays of art.52 Instead, it was destined for Revel’s home where it was to hang among many other gilded framed paintings. It was one of seven family portraits he owned at the time of his death: five were kept in the same bedroom on the first floor of the main house on his country estate, while two hung in the living room (salle) in town. Both were spaces in which he probably entertained only privileged friends. The bailiffs who listed the furnishings did not extract these family items for special valuation at the end of the inventory as they did paintings in other genres. They were part and parcel of the furnishings rather than having any intrinsic artistic or financial value.53 In these spaces, they were for the consumption of family, friends and servants – those who were invited into the home where Revel might quite decorously have greeted them in one of his nightgowns.

Conclusions

Donat Nonnotte’s portrait of Jean Revel is a treasure because so few portraits of the eighteenth-century Lyonnais bourgeoisie apparently survive - in public collections, at any rate. Reading it as a contemporary would have done, however, requires the expertise of dress and furniture historians. As Claudia Brush Kidwell has underlined, interpretation ought always to be a collaborative process drawing on expertise from different disciplines.54 In this case, the happy coincidence of the survival of complementary textual evidence, has made the task more straightforward, as has the relatively full documentation of the background of both sitter and painter. As a model of his age, rank and means, Revel presents a surprisingly modest figure – his wealth was such that he could have afforded more lavish dress or some artistic licence – a nightgown made of the kind of silk which he had designed. Instead, Revel chose an ensemble which visitors to his home in the rue Sainte Catherine might have recognised, suitable for that private space where he socialised with his own circle.55 He wore it wrapped around him, tied close and with formal accessories, all buttoned up. Indeed, in this pose, the difference between formal coat and nightgown would have been minimal. By the age of 63, after more than 25 years as a merchant, Revel probably chose a nightgown to reflect his current preoccupations rather than his artistic past – he was now semi-retired, still in contact with silk manufacturing but also in charge of a country estate. He had authority and responsibilities, and was ageing. He also belonged to the Lyonnais middling ranks, who tended to eschew excessive and eye-catching personal adornment, lavishing more income on their domestic interiors than on their own appearance, and leaving the city’s nobility and its liberal professions to buy more extreme fashions.56 Fashion and conservatism, formality and informality, frugality and flair meet in the portrait. Revel shows that he was not out of touch, even if he retained certain accessories from his youth; the fabrics were up-to-date but not overly expensive and the combination of colours suited his shrewd blue eyes. The very specificity of the garments, accessories and furniture and their relationship to his actual wardrobe and apartment reveal behaviour that is all too easily lost in the lists of clothing found in inventories.

In this portrait the clothes suggest how a particular provincial bourgeois wished his nearest and dearest to see and remember him. The message and conventions are not transparent now, but methodical analysis of such images pays dividends and offers some insights into how the French eighteenth-century bourgeoisie thought about their appearance, its appropriateness and impact. Rapid comparison of Van Loo’s portrait of an unknown man with Nonnotte’s of Revel underlines the chasm between aristocrats and bourgeois (figs 5 & 6). The gorgeous brocaded silks Revel had manufactured were indeed suitable for nightgowns and acquired by the aristocracy. The merchants who conceived them did not attempt to emulate that aristocratic brilliance or expenditure in their dress – nor, one suspects, the deliberately dramatic attitudes and gestures with which they showed off their opulence in the three-quarter or full-length canvasses they commissioned.

Appendix: Revel in Brief (A biographical overview)

Jean Revel, second son of Gabriel Revel (1643–1712) and Jeanne Boudon, came of a long line of painters from Château-Thierry in the Champagne.57 His father, a portrait and history painter, moved to Paris in the early 1670s where he worked under the patronage of Charles Lebrun (1619–90) for the Court, becoming a member of the Académie Royale in 1683, the year before Jean’s birth. Jean was born and baptised in Paris in St Hypolite, the parish that served the Gobelins, as had been his siblings Marie (1678–1755) and Gabriel (1679–1749).58 When Jean was just eight years old in 1692, Revel senior established himself in Dijon, though he kept a virtual foot in the capital as a peintre du roi by writing dutifully to the Académie once a year throughout his life.59 Dijon, the centre of the Burgundian Parlement, was dominated by the legal aristocracy. This environment provided the springboard for Gabriel senior’s career as he spread Lebrun’s doctrine, practising almost without competition. He was wealthy enough by 1698 to acquire a country estate in Longvic near Dijon, where he set up a studio in which to work.60 He was 55 and his son Jean was 14, the usual age to start an apprenticeship.

Unfortunately, there is no record of any apprenticeship nor of Jean’s actions until 1712 when he and his elder brother Gabriel are first recorded in Lyon, one of them registered as a master in the painters’ guild (corporation des peintres et des sculpteurs). Whether this was Jean or his elder brother is not clear.61 They may both have trained in their father’s workshop, which would explain why neither is recorded in any other guild records. They were by then already married to Marguerite (d.1746) and Marie Chaillot Delessinet (d. before 1714), daughters of Gaspard Chaillot Delessinet, a barrister at the high court of appeal of Grenoble (avocat au Parlement de Grenoble). Marguerite bore Jean four daughters and two sons between 1712 and 1717. The girls survived beyond their majority and married into the upper echelons of Lyon’s manufacturing families. They in turn parented grandchildren who achieved material and social success.62

Revel’s stated occupation altered over time, the baptismal records in 1712 and 1713 called him – probably mistakenly - a barrister (avocat en parlement).63 By the time of his first son’s birth in 1715 he was described as a freeman (bourgeois), in 1716 and 1717 as a marchand or marchand bourgeois.64 The last was a Lyonnais term which corresponded to the Parisian négociant in the early years of the eighteenth century. It implied business dealings of different sorts, often of a fairly capital intensive nature.65 The trades of his children’s godparents echoed the profession accorded to Revel at the time of their baptisms. Thus, in 1712 and 1713, a bias towards the legal confraternity was evident, whilst in the following years godparents were from the bourgeois or merchant classes. Presumably this was a reflection of the circles in which the Revels were moving at the time. Increasingly, the emphasis fell on the type of society for which Lyon was famed - the middling, commercial classes whose families were often deeply involved in silk manufacturing.66 As they became his main associates, he moved from the densely populated central presqu’île amid a heterogenous range of trades to the the heart of business in the northern presqu’île, and from the parish of St Nizier in 1712 to St Pierre et St Saturnin by 1716.

The only actual evidence of Revel’s business activities dates to the 1730s and 1740s when they seem to have revolved around the production of metal yarns for silks (dorures). In the hierarchy of business activities in Lyon such production was at the top amongst the transactions of the powerful providers of raw silk, the marchands de soie.67 It involved the making of real gold and silver into yarns for weaving into particularly elaborate and costly silks, which required substantial capital investment. It was therefore an occupation of great prestige, undertaken by the richest merchants in Lyon, who mixed their dealings in raw materials with banking services. It did not necessitate registering with the silk weaving guild (Grande Fabrique). On a small scale, some merchant manufacturers also made such threads in workshops on the premises in which they stored raw materials and finished goods. In 1731, Revel (marchand de dorures in this contract) agreed to take into his business Marguerite-Etiennette Laurent, the daughter of another Lyonnais merchant, and teach her all about the business of dorures.68 Subsequently, in the early 1750s, when Revel went into partnership with his sons-in-law, Jean-François Clavière and Louis Rambaud (Clavière, Revel et Rambaud), he and his partners rented two workshops for working the gold and silver necessary for the making of their fabric.69It was also during this partnership that Revel took on a design apprentice who was the son of an architect from Dijon, surely no coincidence given Revel’s own background and likely social circles in Dijon.70

Revel’s application to design first surfaces late in his career – in the early 1730s, when he was already in his late forties and had lived in Lyon for nearly two decades. Four designs dated to around 1733 bear his name: two sketches in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, and a sketch and a technical drawing (mise-en-carte) in the Musée des Tissus in Lyon.71 None of these drawings reveals precisely Revel’s role in its creation, whether he was indeed the designer/author, or, as is quite possible, their owner, the merchant who commissioned them. He could have been both designer and owner.72 The inscriptions are tantalising. The first reads, ‘Fond argent de Mr Buisson et Revelle en chenille les feuilles des trois vert chenille les fruits argent frisé et sans liage découpé par une soye rentré en ponceau marqué par les traits’.73 The twinning of Buisson with Revel suggests the drawing is the product of a partnership. In the context of the Lyonnais manufacturing community, such a partnership could have been a design studio or a silk manufacturing firm. Buisson was, no doubt, the Benoît Buisson bourgeois, who was important enough in the Revels’ life in 1716 to become godfather to Revel’s first son.74 It seems that fifteen or so years later, he – or a member of his family, perhaps his son – was still in Revel’s life, as a Buisson signed just below Revel’s brother on the marriage contract of Revel’s second daughter.75 The second sketch is similar in appearance so presumably dates to around the same year. It bears the mysterious words, ‘Revelle a vous seule’ (‘Revel for you alone’ or ‘Revel to you alone’), a decided exclusion of Buisson which may be significant in determining who had actually authored the design. In contrast, the third was annotated simply,‘Gros de tours fond blanc. Revel’.

The fourth design is an altogether different affair. It represents the technical application of drawing, for it is a mise-en-carte. The luxuriant motif is executed in water colour on ruled paper (paper divided into squares that represent groups of warp and weft threads on the loom, with the name of the engraver at the foot). In the Lyon tradition, on the back are certain written instructions: a number (No. 49), below which is a key to the treatment of the colours on the loom, and then the place and date, and the name of its owner (‘a Lyon 22e decembre 1733. J. Revel.’) (fig. 1). The owner here has signed, and his signature conforms to that of Jean Revel on the many rites of passage discussed above. Again, this signature does not confirm beyond the shadow of a doubt the actual authorship of the design, as many firms traded under the senior partner’s name and, as the investor of most funds, he was the main signatory on all business papers. The design work attributed to Revel, whether as author or owner, evidently introduced certain innovations, notably points rentrés or what might now be called berclé. This involved creating subtle shadings in woven motifs, often fruit or flowers, by interlocking two different shades rather than having them meeting edge to edge and thus creating a hard line. It is impossible at two centuries’ distance to be sure that Revel was the first to introduce such shading into silk design. Other designers, such as Monlong, Deschamps and Barnier were already attempting to create more naturalistic designs which seem very similar to those by Revel.

Revel’s consolidation of his links with silk manufacturing led him to present substantial dowries of 33,000 livres to each daughter, including merchandise to a greater or lesser extent, and establishing business partnerships with his sons-in-law. This consolidation harked back to his choice of career for his only son, Louis, who had been registered as an apprentice in the silk-weaving guild in 1734. When Louis died prematurely in 1740, he was already a journeyman.76

Revel was wealthy when he died - in Lyonnais bourgeois terms, if not in Lyonnais or Parisian noble terms.77 At a conservative estimate, he was worth about 182,300 livres. He owned a country estate on the Ile Barbe, three leagues from Lyon, a flat in the rue Sainte Catherine in the heart of the quartier des Terreaux, and a third of a building in rue de l’Oursine in Paris in the faubourg St Marcel, as well as movable possessions of high monetary and cultural value.78 His executors paid off the legacies in his will over a number of years, the smaller ones within a month or so of his death: 500 livres for pious works, 100 livres for each of his six servants (probably the equivalent of about six months worth of wages), and 1,200 livres for his housekeeper (gouvernante). The major beneficiaries were his daughters and grandchildren: 45,000 livres for Claudine, femme Lescallier’s children; 12,000 livres for Marguerite and 33,000 livres for the children of her marriage with Jordain; and 45,000 livres for the children of Marie-Catherine, femme Rambaud. He left the rest of his estate to his second-oldest daughter Jeanne-Barbe, femme Clavière. With her share, the estate was worth considerably more – at least a further 45,000 livres, if Revel were being even-handed in his treatment of his daughters as he had been at the time of their marriages. The country house and its land remained in the hands of the Clavière branch of the family until it was confiscated during the French Revolution.79

Endnotes

-

This article is an extended version of a short piece published in a festschrift in honour of Dr Ann Saunders in 2010, Miller, Lesley E. ‘An Enigmatic Bourgeois: Jean Revel Dons a Nightgown for his Portrait’. Costume 44 (2010): 46–55. I am grateful to Verity Wilson and Penny Byrde, the editors of Costume, for encouraging me to publish the more detailed version. I thank my colleagues Clare Browne, Sarah Medlam, Susan North and Moira Thunder for their helpful comments as I prepared this text; Sylvie Martin-de Vesvrotte for providing information from her unpublished dissertation; Audrey Mathieu at the Musée des Tissus, Gérard Bruyère and his colleagues at the Musée des Beaux-Arts, both in Lyon, for their willing assistance; and the Royal Ontario Museum where I spent a month as Veronika Gervers Fellow in Textile History, in particular to Alex Palmer, Anu Livandi and Nicola Woods for facilitating my ongoing requests. Angela McShane, editor of the Online Journal has been a thoroughly encouraging and rigorous editor. ↩︎

-

Their monographs are: Thornton, Peter K. Baroque and Rococo Silks. London: Faber and Faber, 1965; Rothstein, Natalie. Eighteenth-century Silk Designs in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: V&A/Thames and Hudson, 1991. ↩︎

-

Thornton. Baroque and Rococo Silks. 15. ↩︎

-

Thornton, Peter K. ‘Jean Revel, Dessinateur de la Grande Fabrique’. Gazette des Beaux-Arts (1960) : 71–86. Thornton. Baroque and Rococo Silks. 15. The rich documentation on Revel available now in the Archives Départementales du Rhône was not readily accessible in the 1950s. ↩︎

-

The most thorough and impressive investigation derives from research into the collections of the Abegg-Stiftung in Switzerland. Jolly, Anna. Seidengewebe des 18. Jahrhunderts II, Naturalismus. Riggisberg: Abegg-Stiftung, 2002. The banyan in fig.4 and the sack back gown Museum no. T.193-1958 reveal the use of this style of silk two or more decades after it was originally made, either in France or elsewhere. ↩︎

-

Miller, Lesley E. ‘Designers in the Lyons Silk Industry, 1712–87’. Unpublished PhD thesis, Brighton Polytechnic, 1988; Ibid. ‘Jean Revel: Silk Designer, Fine Artist, or Entrepreneur?’. Journal of Design History 8:2 (1995): 79–96; Ibid. ‘Dressing down in eighteenth century Lyon: dress in the inventories of twenty-seven silk designers’. Costume 29 (1995): 25–39. ↩︎

-

Most eighteenth-century authors reiterated almost verbatim the comments in Pernetti, Jacques. Les lyonnais dignes de mémoires. Lyon, 1757; Leroudier, Émile.‘Les dessinateurs de la soierie lyonnaise au dix-huitième siècle’. Revue d’Histoire de Lyon. 1908: 241–266; Thornton. ‘Jean Revel, Dessinateur de la Grande Fabrique’: 71–86. ↩︎

-

Miller. ‘Jean Revel: Silk Designer, Fine Artist, or Entrepreneur?’. ↩︎

-

Pernetti. Les lyonnais dignes de mémoires: 350. ↩︎

-

AML St Pierre et St Saturnin : Sépulture 8 avril 1785, no. 921; St Nizier : 11 janvier 1789 Sépulture Noble Jean-François Clavière. ↩︎

-

On the back is written: ‘Nonnotte pinx. 1748’. I am grateful to Audrey Mathieu of the Musée des Tissus in Lyon for confirming that the painting entered the museum some time before 1914. Opened in 1864, the Musée d’Art et d’Industrie took the name Musée Historique des Tissus in 1891, its partner institution becoming the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. François Breghot de Lut indicated that it was hanging in the director’s office at the time he was editing the text of Le livre de raison de Jacques-Charles Dutillieu. Lyon:1886, so it must have arrived in the museum before that date. Breghot de Lut, 24. ↩︎

-

Miller, ‘Jean Revel: Silk Designer, Fine Artist, or Entrepreneur?’: 79–98. This is the most up-to-date account, and a chapter in my forthcoming book, Portraits in Silk, will present the evidence discovered since 1995. There is no evidence of him joining the guild, but the relevant guild registers have not all survived. ↩︎

-

Miller. ‘An Enigmatic Bourgeois’: 86. Based on Maurice Garden’s sampling of three decades of inventories: Garden, Maurice. Lyon et les Lyonnais. Lille: Presses Universitaires de Lille, 1970. ↩︎

-

Perez, Marie-Félicie. ‘La maison de campagne d’un échevin lyonnais au XVIIIe siècle’. In Lyon et l’Europe. Hommes et Sociétés. Mélanges d’histoire offerts à Richard Gascon. Lyon: Presses Universitaires de Lyon, 1980: 113. ↩︎

-

Archives Départementales du Rhône (hereafter ADR) 3E2999 Bourdin (Lyon): 8.08.1742 Vente d’un domaine et fonds Mr Ranvier/Mr Revel. He had paid off the full amount of 20,000 livres; 3E3904 Debrye (Lyon) : 31.03.1746 Vente d’une maison à Lyon Appelée l’hôtel des quatre nations et dépendances Sindics des créanciers du Sr Duport/Srs Revel et Clavière. He paid 58,218 livres in cash for his share. ADR BP2187, f. 56. For the status of the rue Sainte Catherine, see Bayard, Françoise. Vivre à Lyon sous l’Ancien Régime. Lyon: Perrin, 1997: 242. ADR BP2187: 14.12.1751 Inventaire après-décès Revel, f. 56. ↩︎

-

ADR 3E6913B Patrin (Lyon): 25.11.1751 Testament Revel; Archives Municipales de Lyon (hereafter AML) St Pierre et St Saturnin, 1751, no. 954: Enterrement de Jean Revel marchand ↩︎

-

Viaux-Locquin, Jacqueline. Les bois d’ébénisterie dans le mobilier français. Paris : Léonce Laget, 1997: 141–3. Its popularity decreased in the later eighteenth century. ↩︎

-

ADR BP2187, ff. 39–44. See also, Pardailhé-Galabrun, Annik. La Naissance de l’Intime. 3000 foyers parisiens XVIIe – XVIIIe siècles. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1988: Chapter 10 on interior decoration of Parisian houses. Revel’s interiors fits the profile for the late seventeenth and first half of the eighteenth century. ↩︎

-

Garden, Lyon and Lyonnais, 405ff. ↩︎

-

ADR BP2187, ff. 51–3. ↩︎

-

Martin, Sylvie. ‘Vie et œuvre de Donat Nonnotte, peintre du XVIIIe siècle’. Unpublished mémoire de maîtrise, Université de Lyon II, 1984. tome 2, 60. ↩︎

-

The first record for Nonnotte in Lyon is in 1751. He had married Marie-Elisabeth Bastard de la Gravière in Paris in 1737. Audin, Marius, and Amable Vial. Dictionnaire des artistes et des ouvriers d’art du Lyonnais. Paris : Bibliothèque d’art et d’archéologie, 1918–1919: Vol. II: 73; Martin, ‘Vie et œuvre de Donat Nonnotte, peintre du XVIIIe siècle’; ADR 3E3876 Dalier (Lyon): 4.03.1783 Testament Nonnotte. The inventory taken after his death on 17.03.1785 is in the ADR Série BP. ↩︎

-

Martin, Sylvie. ‘Les portraits de femmes dans la carrière de Donat Nonnotte’. Bulletin des musées et monuments lyonnais 3–4 (1992): 35. It was not uncommon for Parisian artists to visit Lyon for several months at a time, sometimes en route to or from Rome, though Nonnotte himself did not make that pilgrimage. Few stayed permanently in Lyon, although the most eminent artists active there between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries came from outside the city. Chomer, Gilles and Marie-Félicie Perez. ‘Un foyer artistique’. In Histoire de Lyon des origines à nos jours, edited by André Pelletier et al: 550–580. Lyon: Éditions Lyonnaises d’Art et d’Histoire, 2007. ↩︎

-

‘Le portrait… sert à conserver et à exprimer les sentiments du respect, de l’estime, de l’amitié et de l’amour. On se tromperait si l’on croioit que la ressemblance des traits fit tout le mérite d’un portrait’, cited in Les peintres du roi 1648–1793. Exhibition Catalogue. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours. Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2000: 162. ↩︎

-

Desvernay, Félix. Le vieux Lyon à l’Exposition Internationale Urbaine, 1914. Description des œuvres, objets d’art et curiosités; Notices biographiques et documents historiques inédits. Lyon, 1915: 57, cat. 179 : ‘en perruque, vêtu d’une robe de chambre fourrée, en soie grise, à larges dessins. Il regarde souriant le spectateur et tient ses bras croisés sur le dos d’un fauteuil rouge’. ↩︎

-

Martin. ‘Vie et œuvre de Donat Nonnotte’. tome 2, cat. no. 31, 58–60 : ‘vêtu d’une robe de chambre fourrée et brochée de couleur grise, entourée d’un cordon bleu. Il regarde souriant le spectateur et tient ses bras croisés sur le dos d’un fauteuil rouge…Tout dans ce tableau rappelle les activités du peintre: d’abord, la robe de chambre brochée avec ses motifs floraux qu’il affectionnait particulièrement, puis la tapisserie apparente du fauteuil qui présente une similitude de décoration avec la robe de chambre d’intérieur du peintre.’ ↩︎

-

A number are shown in Martin. ‘Les portraits de femmes dans la carrière de Donat Nonnotte’: 26–49. ↩︎

-

A number of silk, wool and worsted damask nightgowns survive in museum collections in France, UK and USA. See, for example, Swain, Margaret. ‘Nightgown into Dressing Gown. A Study of Men’s Nightgowns in the Eighteenth Century’. Costume (1972): Appendix, 19–21; Modes en miroir. La France et la Hollande au temps des Lumières. Paris: Paris Musées, 2005. cats. 85 & 123. Worsted was a wool cloth, sometimes glazed and often made with patterns imitating those on silks. It was not quite so expensive and probably warmer. According to Savary des Bruslons (1688), it was made in northern France and the Low Countries, in Antwerp, Lille, Tourcoing, Roubaix and Tournai in the late seventeenth century. Cited in Havard, Henri. Dictionnaire de l’Ameublement. Paris: Maison Quantin, 1887–90: I: 530. Interestingly, not a cloth named in the inventories of textile retailers in Lyon as studied by Françoise Bayard for the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Many other types of woollen cloths were available, drap being valued at 3 livres per ell in 1730, other woollens at 10 – 60 sols. Silk damask was valued at 7 – 17 livres per ell in 1725; satin at 3 – 8 livres. ‘De quelques boutiques de marchands de tissus à Lyon et en Beaujolais aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles’. «De la fibre à la fripe». Le textile dans la France méridionale et l’Europe méditerranéenne XVII-XXe siècles. Actes du colloque du 21 et 22 mars 1997, edited by Geneviève Gavignaud-Fontaine, Henri Michel & Elie Pélaquier. Montpellier: Conseil Général de l’Hérault, Conseil régional du Languedoc-Roussillon et Conseil Scientifique de l’Université de Montpellier III. Paul Valéry, 1998: 450–3. ↩︎

-

Brush Kidwell, Claudia. ‘Are Those Clothes Real? Transforming the Way Eighteenth-Century Portraits are Studied’. Dress 24 (1997): 3–15. On method, see, too, Taylor, Lou. The Study of Dress History. Manchester: MUP, 2002; Ribeiro, Aileen. The Art of Dress Fashion in England and France 1750–1820. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995. ↩︎

-

Turning clothes was a method of prolonging their life. It involved the unpicking of all seams and the turning inside out of the garment so that the less worn side became the outer side. This laborious form of economy was common practice at all levels of society in this period, as the fabrics cost more than sewing labour. Accordingly, fabrics were recycled till no longer usable. ↩︎

-

Justaucorps (rather than the more up-to-date and less specific habit). The latest reference I have to the use of this word in an inventory for these men is 1770. See Miller. ‘An Enigmatic Bourgeois’. ↩︎

-

It contained no fabrics from the very top level of the textile hierarchy as defined in a petition drawn up for De Gournay in 1751. Cited in Godart, Justin. L’ouvrier en soie. 1899, reprint Geneva: Slatkine, 1976: 390. ↩︎

-

ADR BP2187. Some ten years later, on 19 November 1760, a tailor advertised suits for autumn and winter in the Affiches de Lyon, no. 47: 192. The cost of a full suit of cloth lined in cotton was 74 livres, while a suit lined with silk cost 125 livres. A surtout and breeches of velvet cost 180 livres. ↩︎

-

Petition of 1786 cited in Godart. L’ouvrier en soie: 410. It should be noted, however, that the consumption of clothing and rapidity of change had increased considerably by the end of the century, and that Revel belonged to the first half of the century. Roche, Daniel. The People of Paris. Oxford: Berg, 1981: Chapter 6; Ibid. The Culture of Appearances. London: Berg, 1996: Chapters 6 & 7; Bayard. Vivre à Lyon: 258–9. ↩︎

-

For a similar design for silk damask, by Anna Maria Garthwaite, dated 1748, see Rothstein. Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century: 238. A number of other designs from 1743–51 are in a similar idiom. ↩︎

-

On eighteenth-century whitework, see, The Art of the Embroiderer by Charles Germain de Saint-Aubin Designer to the King. Translation and annotation of text of 1770 by Nikki Scheuer. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum, 1983: 57 & 126. See, too, Bleckwenn, Ruth. Dresdner Spitzen-Point de Saxe. Dresden: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Kunstgewerbenmuseum, 2000: cat. 40, dated to 1730 - 50. Here, the whole flounce is covered with stitching, whereas Revel’s is only decorated round the edge. The nature of the design is similar. ↩︎

-

Ribeiro, Aileen. Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe. London: B.T. Batsford, 1984: 89. Marcia Pointon devotes a whole chapter to the significance of wigs in her seminal work on English eighteenth-century portraiture. Pointon, Marcia. ‘Dangerous Excrescences: Wigs, hair and masculinity’, in Hanging the Head: portraiture and social formation in eighteenth-century England. Marcia Pointon. London: Yale University Press, 1993:107–136. Lyon had its own guild of barbiers, perruquiers, baigneurs et étuvistes, established formally by royal decree in 1673. Between 1711 and 1774, the number of offices available rose from 60 to 101. Caillat, Gilles. ‘Les Perruquiers de Lyon au XVIIeme et XVIIIeme siècle’. Unpublished mémoire de maîtrise, Université Lumière Lyon II, 1992: 20. This increase was probably in line with the increase in population and therefore demand for wigs. This level was about nine times lower than for the much bigger city of Paris. ↩︎

-

Revel also owned many nightcaps which would have been perfectly congruous to wear with a nightgown. ADR BP2187. ↩︎

-

Callimanco was a fine worsted, usually patterned; swanskin a soft woollen cloth. Chambaud, Louis. Nouveau dictionnaire françois-anglois & anglois-françois: contenant la signification des mots, avec leur différens usages, les constructions, idiomes, façons de parler particulières, & les proverbes usités dans l’une et l’autre langue, les termes des sciences, des arts, & des métiers, le tout receuilli des meilleurs auteurs anglois & françois. London: John Perrin, 1778. All translations are taken from this dictionary which describes the textile briefly before giving the equivalent in the other language. Florence M. Montgomery offers the English translation of calemande, with a fine explanation by Postlethwayt whose dictionary drew heavily on that of Savary des Bruslons, published in France in 1723–30. See Textiles in America, 1650–1870: a dictionary based on original documents, prints and paintings, commercial records, American merchants’ papers, shopkeepers’ advertisements, and pattern books with original swatches of cloth. New York: Norton, 1984: 184–5. Molleton in 1750 was valued at 38 – 39 sols per ell in 1730 and 55 sols in 1789 in Bayard’s inventories for the region, so was neither a very cheap nor very expensive fabric. Bayard. ‘De quelques boutiques de marchands de tissus’: 451. ↩︎

-

ADR BP2187, ff. 41 and 14. A Lyonnais tailor advertising in the Affiches de Lyon ten years later, promoted garments of much more expensive fabric in three pieces, the cheapest being a redingote à l’Ecuyère, veste et culotte de Camelot mi-soie, galonée d’argent avec les jarretières de même at 70 livres (brand new, this three piece suit, whose coat would have required substantial interlining and shaping, was made of a wool and silk mix camblet, and had a fancy metal trimming). Affiches. 1761: 72. ↩︎

-

Pardailhé-Galabrun. La Naissance de l’Intime: 398–401. ↩︎

-

ADR BP2187, f. 40. I am grateful to Sarah Medlam for her help in identifying the style and its implications at this date. Ferrier, André. ‘Nogaret et sa manière de galber un siège Louis XV’. Connaissance des Arts 1 (1959) : 114–7; Kjellberg, Pierre. Le mobilier français du XVIIIe siècle. Dictionnaire des ébenistes et menuisiers. Paris: Les Éditions de l’Amateur, 1989 : 603–7. The chair in the portrait conforms in style to the surviving piece shown in, Pallot, Bill G. B. L’art du siège au XVIIIe siècle en France. Paris: A.C.R.-Gismondi Éditeurs, 1987: 251. This chair was made in walnut around 1760 by the top furniture makers, Nicolas Heurtaut and Jean-Baptiste Tilliard. ↩︎

-

John Hardy’s appraisal of the furniture of the English portrait painters Joshua Reynolds and Richard Cosway makes a useful contribution to the subject. Hardy, John.‘The Discovery of Cosway’s Chair’. Country Life (March 15, 1973): 705–6. Cosway’s chair, made about 1765–8, is in the V&A collection and was used in portraits into the 1770s. Armchair, M.Lock, ca.1755. Museum no. W.1-1973. ↩︎

-

On significance of nightgowns, see Swain. ‘Nightgown into Dressing Gown’: 10–21; Cunningham, Patricia A. ‘Eighteenth Century Nightgowns: The Gentleman’s Robe in Art and Fashion’. Dress 10 (1984): 2–11; Maeder, Edward. ‘A Man’s Banyan: High Fashion in Rural Massachusetts’. Historic Deerfield magazine (Winter 2001); Fennetaux, Ariane. ‘Men in gowns: Nightgowns and the construction of masculinity in eigtheenth-century England’. Immediations. The Research Journal of the Courtauld Institute of Art 1 (Spring, 2004): 77–89; Ibid. ‘Du boudoir au salon: l’inimité et la mode en Europe au XVIIIe siècle’. In Modes en miroir. La France et la Hollande au temps des Lumières. Paris: Paris Musées, 2005: 72–3; Thunder, Moira. ‘An Investigation into Masculinities and Nightgowns in Britain, 1659–1763’. Unpublished MA dissertation, University of Southampton, 2005. ↩︎

-

See, for example, the Netherlandish textile merchant in similar garb, Willem Van Mieris le Jeune, Gamaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden. Inv. 1752. ↩︎

-

Les peintres du roi 1648–1793; Citizens and Kings. Portraiture in the Age of Revolution 1760–1830. Exhibition Catalogue. London: Royal Academy of Art, 2007; especially ‘The Cultural Portrait’ and ‘The Place for Experimentation: Artists’ Portraits and Self-portraits’: 128–80. Nonnotte’s work can be compared with that of his Parisian contemporaries François-Hubert Drouais, Maurice Quentin de Latour, Jean-Baptiste Perronneau, Louis-Michel Van Loo and Louis Toqué, all of whom enjoyed depicting the specificity of fashionable dress – usually in an indoor setting. ↩︎

-

It had been used in the artist’s self-portrait four years earlier. On Louis-Michel Van Loo’s studio props, see Rolland, Christine. ‘Louis Michel Van Loo (1707–1771): Member of a Dynasty of Painters’. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of California, Santa Barbara, 1994: Chapter 3; Ribeiro. The Art of Dress: 15–18. ↩︎

-

Ribeiro. The Art of Dress: 18, citing Diderot. ↩︎

-

Diderot, Denis. ‘Regrets sur ma vieille robe de chambre ou avis à ceux qui ont plus de goût que de fortune’. 1772. Accessed May 30, 2012. https://www.bmlisieux.com/archives/diderot.htm. Diderot’s essay is a masterpiece in associating different levels of nightgown with other objects and how comfort could be lost as status rose. His comfortable favourite nightgown from previous years was, like Revel’s made of callimanco (calemande). ↩︎

-

The addition of a collar was in line with the addition of a collar to the formal coat towards 1760; the fabric is a plain silk – perhaps more like the satin nightgown mentioned in Revel’s inventory. ↩︎

-

For example, McNeill, Peter. ‘ “That Doubtful Gender”: Macaroni Dress and Male Sexualities’. Fashion Theory 3: 4 (1999): 411 – 47; Ibid. ‘Macaroni Masculinities’. Fashion Theory 4:4 (2000): 373–404; Munns, Jessica and Penny Richards (eds). The Clothes That Wear Us. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1999. ↩︎

-

The first public exhibition in Lyon was in 1786. Perez, Marie-Félicie. ‘L’exposition du Salon des Arts de Lyon en 1786’. Gazette des Beaux-Arts (décembre 1975): 198–206. ↩︎

-

ADR BP2187, f.45 in town; f. 13 in country. It seems likely that Revel had a pendant of his wife painted or that it already existed. They were valued as a pair at 8 livres (f. 45). At 4 livres a piece, they were more highly valued than many of the landscapes, history and religious paintings valued separately by an expert (ff. 51–3). ↩︎

-

Brush Kidwell. ‘Are Those Clothes Real?’. In this respect, much British scholarship over the last thirty years, has acknowledged the need for teamwork, especially when exhibitions on portraiture have been staged. The most recent example of a relevant exhibition in London was Van Dyck and Britain. London: Tate Britain, 2009, which included as exhibits examples of dress, sound catalogue entries by the dress curator Susan North and an essay on men’s fashion by the eminent fashion historian, Christopher Breward. The leading exponent of the interpretation of dress in art has been Aileen Ribeiro, who first collaborated in this way on the Batoni exhibition held at Kenwood House in 1982, and has since been called upon regularly to participate in similar projects in the UK and USA. This approach does not seem to have been adopted in French scholarship, perhaps because the academic study of dress has yet to be established in French universities. Here, I would like to note my own debt to my colleagues in the Furniture, Textiles and Fashion Department at the V&A, as Sarah Medlam gave useful insights into the chair, while Clare Browne and Susan North shared their views of the textiles and dress respectively. Sylvie Martin’s art historical work is essential as a basis for understanding Nonnotte’s practice. My own research on the social and cultural environment of eighteenth-century Lyonnais silk designers complements all of this expertise and scholarship. ↩︎

-

Ribeiro makes the point that deshabillé in French portraits was ‘of the most lavish kind with emphasis on the beautiful fabrics of the costume’, citing François-Hubert Drouais, Group Portrait, 1756 in the National Gallery of Art, Washington as an example (Ribeiro. The Art of Dress: 35). Revel offers an interesting contrast from a different social class. ↩︎

-

Garden. Lyon and Lyonnais: 405. ↩︎

-

His father and uncles were all painters, as had been his grandfather, although his father elevated himself by becoming a Royal Academician. Brême, Dominique. ‘Gabriel Revel (1643–1712): Un peintre de Château-Thierry au temps de Louis XIV’. In Mémoires de la Fédération des Sociétés d’Histoire et d’Archéologie de l’Aisne. t. XXVII, Noyon, 1982 : 13–25 ; Ibid. ‘La peinture en Bourgogne au XVIIe siècle: Gabriel Revel (1643–1712) et la diffusion de l’art officiel’. In Mémoires de l’Académie des Sciences, Arts et Belles-Lettres de Dijon. t.CXXV, 1983 : 91–101. ↩︎

-

Sadly, the registers for 1684 were destroyed by fire at the Hôtel de Ville in 1871, but the baptisms of his siblings Marie and Gabriel offer the first impression of the family. Gabriel went to Lyon with Jean and died there two years before him. Marie’s godfather was a deputy procurator general to the Grand Conseil (substitut du procureur général au Grand Conseil), her godmother was the wife of an official in the household of the Princess Royal (officier de Mademoiselle) and a relation of her mother’s. The young Gabriel’s godfather was his uncle, the painter Claude Revel, whilst his godmother was the daughter of a joiner by appointment to the Royal buildings (menuisier ordinaire des bastimens du roy). For details of Gabriel Revel’s career, see Brême. For details of baptisms of Marie and Gabriel, see Bibliothèque Nationale de France (hereafter BN) N.A Fr. mss. 12178, 2 Mai 1678 and 20 août 1679. The names of the godparents were Jacques Genard, Barbe Boudon (wife of Jacques), Claude Coutan; AML St Pierre et St Saturnin : no. 420, 22 mai 1749: ‘Sr Gabriel Revel négotiant décédé hier montée du Grifon agé d’environ septante ans a été inhumé dans l’eglise de St Pierre.’ ↩︎

-

Brême.‘Gabriel Revel’: 99. Coural, Jean. Les Gobelins. Paris, 1989: 10–19. ↩︎

-

Brême. ‘Gabriel Revel’: 100. ↩︎

-

It is unlikely that it was another Revel as the name was fairly uncommon in eighteenth century Lyon unlike Revol, Rival and Rivet. AML HH174 Corporation des peintres et des sculpteurs. Revel was one of the guild members who contributed to the repairs made to the guild chapel on 1 December 1712. Records of the deliberations of the silk weaving corporation do not mention Revel as a member and none of the surviving registers of apprenticeships or masters in the Archives Municipales de Lyon indicate his presence. ↩︎

-

The marriage acts and contracts have not been found yet, but Jean’s first child was baptised in the parish of St Nizier in Lyon in 1712, as was Gabriel’s (AML, St Nizier:18 juin 1712 Baptism of Catherine, Gabriel’s daughter by Marie Thérèse Delessinet, and 15 juillet 1712 Baptism of Claudine, Jean’s daughter). Marie Thérèse subsequently died between 1713 and 1714, Gabriel remarried in 1717 this time in the parish of Sainte Croix, for which he required permission from the parish priest in St Nizier. AML St Nizier: 7 juin1717 Remise pour Sainte Croix; Sainte Croix: 8 juin 1717 Mariage Gabriel Revel/Marguerite Charessieu, fille de me Claude François Charesieu, ancien procureur ès cours de Lion et de dame Antoinette Bussière. Jean was a witness at the wedding. This was the cathedral parish. He and his brother were both marchands on this entry. AML St Pierre et St Saturnin: 1 mars1746, f. 55 Enterrement Marguerite Challiot Delessinet, femme de Jean Revel. ↩︎

-

Parish registers are not always totally reliable, although why a newcomer to Lyon, such as Revel, should claim a totally different trade from the one he practised is difficult to explain. At this juncture, even if he were not a barrister (avocat), he obviously moved in those circles and would therefore have been aware of the law worked with regard to policing guild disputes. See, Michael Sonenscher for further details of the way in which the different layers of the legal system worked in eighteenth-century France. Sonenscher, Michael. Work and Wages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989: 53–6. ↩︎

-

AML, St Nizier: 15 juillet 1712 Baptême de Claudine Revel 24 juin 1713 Baptême de Barbe Jeanne, 21 mars 1715 Baptême de Benoît; St Pierre et St Saturnin: 26 août 1716, f.132 Baptême de Marguerite Gabrielle Revel; 9 septembre 1717, f.147 Baptême de Louis Revel. Benoît was apparently the only child to die within the first couple of years of his life. (St Nizier: 29 août 1717 Enterrement de Benoît Revel) ↩︎

-

Later in the century, the Lyonnais began to use the Parisian word. See Garden, Maurice, Lyon et les lyonnais au dix-huitième siècle. Lyon : Flammarion, 1976: 367. ↩︎

-

Claudine’s godparents were François Riverieulx, ancien échevin et ancien président de l’éléction de Riverieux and Claudine Riverieux, wife of Mr Foy de St Maurice, conseiller du roy, président à la cour des monnoyes et commissaires. Barbe Jeanne’s godparents were Antoine Michel, écuyer and Barbe Collemieu, daughter of Jacques Collemieu, marchand. Benoît’s were Benoît Ruisson, bourgeois and Reine Durand, wife of Lambert Laurent, marchand. Marguerite’s were her uncle Gabriel Revel, a marchand bourgeois and his wife-to-be, Marguerite, daughter of François Charessieux procureur ès-cours de Lion. Louis’ were Louis Vandercabel marchand bourgeois and Marie Elizabeth Mayer, wife of César Sonnerat bourgeois. Both Vandercabel and Sonnerat belonged to the corporation des marchands et maîtres ouvriers en soie, came of successful Lyonnais merchant stock and were members of the silk weaving guild. Louis Vandercabel marchand bourgeois died on 28 February 1729 in rue Lafont, aged 60, and was buried in the church of the RR. PP. Carmes. He left a considerable number of paintings as well as merchandise in his home. AML 1GG612: St Pierre et St Saturnin, 1729, f. 59; ADR BP2117: 8.03.1729 Inventaire-après-décès Louis Vandercabel. César Sonnerat died in January 1755, having made a will in 1751. He reckoned that he was worth more than 343,599 livres. ADR 3E4698 Pachot (Lyon): 30.09.1751 Testament César Sonnerat marchand fabriquant en étoffes d’or, d’argent et de soye, bourgeois de Lyon. He owned his house at the corner of rues Buisson and Gentil in Lyon and a country house. ↩︎

-

From the publication of the first Almanach de Lyon in the late 1740s, the marchands de soie were cited as an independent group who did not belong to any corporation. ↩︎

-

ADR 3E4686 Durand (Lyon): 9 avril 1736 Aprentissage Marguerite Etiennette Laurent/Revel. ↩︎

-

‘ouvroirs pour écacher et filer l’or et l’argent nécessaires à la fabrication de leurs étoffes’ (ADR 3E6913A, Bail op.cit., but also 3E6913B: 21 janvier 1751 Louage Revel, Clavière et Rambaud/Dumont).Additional accommodation for the same purpose was rented from the Bureau des petites écoles et du séminaire de St Charles on the Grande Côte des Capucins in 1751. ↩︎

-

ADR 3E6913B Patrin (Lyon): 30.09.1751 Certificat Revel Clavière Rambaud/Gérard Masson. ↩︎

-

Several other drawings by the same hand or after this hand are to be found in the BN, MT, Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, and Victoria and Albert Museum. See, Thornton. ‘Jean Revel, Dessinateur de la Grande Fabrique’. ↩︎

-

Thornton. Baroque and Rococo Silks: 175, Plates 68 & 69; Rothstein. Eighteenth-century Silk Designs: 126–8 & relevant plates; MAD Collection Galais, Vol. 1. The English silk designer, Anna Maria Garthwaite, evidently owned and copied key elements of the technique within a couple of years. ↩︎

-

BN Lh44 – microfilm M253787. Note that Peter Thornton transcribed Buisson as Ruisson, a transcription I followed in my article of 1995. On revisiting the design, it has become clear that Buisson is the correct transcription. It is also a surname that appears a great deal in the registers of the Grande Fabrique. ↩︎

-

AML St Nizier: 21 mars 1715 Baptême Benoît Revel; 29 août 1717 Enterrement. Like the godfather of Revel’s other son, Buisson was substantially older than Revel (twenty years older in his case). ↩︎

-

Or a member of his family. ADR 3E2977: last folio. He died in 1744 at the age of 80, two years before the marriage of the last of Revel’s daughters. AML St Pierre et St Saturnin: 2 mai 744 Enterrement Benoît Buisson, died in rue de la Cage. Witnesses at funeral were Lescallier, Federy fils, Federy père and Jacques Buisson. ↩︎

-

Louis Revel registered as apprentice with Jean Monmarché on 26 November 1732 at the age of 15.He completed his apprenticeship in five years and registered as a journeyman in 1737. AML, HH598 Registre des apprentis (1725–37), f. 227 and HH588 Livre des compagnons 1735–45, f. 66: 4.12.1737. ↩︎

-

Garden. Lyon and Lyonnais: 355–87. ↩︎

-

His universal heir honoured all minor and major legacies immediately. This may, of course, be more of an indication of Jeanne-Barbe’s husband’s solvency than of the state of Revel’s the finances. ↩︎

-

Charléty, S. Documents relatifs à la vente des biens nationaux. Lyon, 1906: 141. ↩︎