Abstract

The Listening Gallery was a collaborative project between the Royal College of Music (RCM) and the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A). This paper, written by a former member of the galleries concept team and the research associate on the ‘Listening Gallery’s’ project, focuses on the innovative integration of new recordings of period music with the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries, covering Europe 300–1600. Many of the pieces had not been recorded previously and all had direct relationships with individual objects in the displays.

The Medieval & Renaissance Galleries at the V&A opened in December 2009. The project began with an initial meeting of the concept team in July 2002. This long gestation period provided the curatorial team developing the displays with an invaluable opportunity to revisit the collections and undertake new research that informed the final displays seen today in a myriad of ways. Alongside traditional museum scholarship, recent museological, visitor, and audience research played an equally significant role in shaping the project. Quantitative evaluation of the previous displays of medieval and Renaissance art at the V&A, showed that they needed radical reinterpretation and redisplay.1 Front-end focus groups were particularly informative in establishing visitors’ levels of knowledge about the medieval and Renaissance periods, their perceptions and misconceptions, and their aspirations for the new displays.2

From the earliest stages of the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries project, the team aimed to develop a layered interpretation that could meet the needs of different audiences. This approach was inspired by the work of learning theorists and other academics who have transformed the way museums conceptualise visitors by highlighting diversity in learning style, preference, intelligence and motivation.3 A multi-sensory framework was devised for the new galleries, incorporating opportunities for tactile experience, active hands-on learning and varied strategies for helping visitors to decode medieval and Renaissance art actively. Each element of the interpretive framework for the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries was a project in its own right but it is the audio provision, and more specifically the music, that is the main focus of this paper. Audio, along with film and other digital media, was also planned from the beginning, informed by evaluative studies that have clearly demonstrated the benefits of such an approach in improving visitor experiences.4 In the case of the new galleries, however, the final provision of music far exceeded the expectations of the project team and, it will be argued here, represents a unique approach in the museum sector.

In the last ten years the use of recorded music in museums has become increasingly prevalent as technologies required to deliver it have become more sophisticated and affordable, and as museums have become more audience-focused. Naturally, museums whose mission is music-focused and whose collections are comprised of musical instruments, manuscripts and printed music have been particularly innovative in integrating recorded music with cased displays.5 Both the Musical Instruments Museum in Brussels and the Museum of Music in Paris have made imaginative use of digital technology to make sound part of the visitor experience.6 The Music Gallery at the Horniman Museum, in south-east London, also provides a good example of a smaller institution that makes effective use of digital table-top interactives that allow visitors to hear the instruments in the displays.7

Yet, as observed by Linda Phyllis Austern, ‘commercially designed mood-altering soundtracks are everywhere’, and so it is hardly surprising that a wide variety of non-specialist museums of various kinds have also turned to music to support exhibition narratives and shape visitor experiences.8 The use of period music to help visitors imaginatively immerse themselves in a historical period is relatively common. The Great City Gallery at the Discovery Museum, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, is an example of an older display that uses music in this way. Here popular music is used to help define key decades in the city’s history throughout the twentieth century.9 For The Sacred Made Real exhibition (October 2009-January 2010) at the National Gallery, audio-guide users were able to view the paintings and sculptures while listening to specially commissioned music performed by a string sextet.10 In other instances commissioned music is used in order to influence the emotions or moods of visitors by evoking an appropriate atmosphere. For The Book of the Dead: Journey to the Afterlife (November 2010-March 2011), a temporary exhibition at the British Museum, a musical soundtrack was commissioned to heighten emotional effect at a key moment in the exhibition narrative.11

In most instances then, non-music specialist museums primarily use music to create an atmospheric background to visiting and viewing, with no obvious or strong connection between the pieces of music and specific objects, and with little information given about the music itself. However, exceptionally, some non-music museums have also used music recordings as a central part of a display; to make a specific intellectual point or to deliver key exhibition messages. For example, The Akan Drum exhibition at the British Museum (August-October 2010), utilised a soundtrack comprised of extracts from fifteen different music recordings to help communicate to visitors the impact of slavery on twentieth-century Afro-American music.12

While generally there appears to be little meaningful visitor research in the public domain that provides detailed insights into the impact of music on museum visitors, the limited evaluation of temporary exhibitions at the British Museum that have incorporated music suggests that visitors responded most positively to ambient music where there is an obvious connection between the soundtrack and the themes of the display.13

The final strategy for integrating music with the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries was certainly informed by other museums’ approaches, but it was most directly influenced by the At Home in Renaissance Italy exhibition, held at the V&A in 2006.14 This exhibition focussed on the domestic context and function of decorative art objects, paintings and sculpture in Tuscany and the Veneto. The emphasis was on the socio-cultural context to which the objects belonged, in contrast to traditional art-historical approaches, offering, through new original research, fresh and innovative insights into the Renaissance home.

The exhibition included a section on entertainment in the home including a display about music incorporating musical instruments and printed music books.15 The ensemble Trictilla were commissioned to record 24 pieces of music contemporary with this display, which were then played in rotation through fixed speakers placed at high level.16 All 24 pieces (more than an hour of music and some never recorded before) were contemporary examples, that could have been performed and heard in a Renaissance home, and also reflected the range of instruments that would have been found there. Several of the pieces performed could also be seen in opened manuscripts on display.

The exhibition brought this music and its performance into the public domain for the first time. Visitors were able to listen to a reconstruction of the domestic Renaissance sound-world that was as accurate as possible and to which the objects in the displays also belonged. The attention to detail was also reflected in the attempt to capture the acoustic environment of a Renaissance interior by making the recordings in the music room of the Palazzo Budini Gattai in Florence. Visitor experience was also extended by making extracts of five of the recordings available on the exhibition’s microsite.17

The methodology and rationale employed for At Home in Renaissance Italy was equally applicable to the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries and a dialogue began, initially between the exhibition and gallery teams at the V&A, and then also with the RCM. Initial discussions soon developed into a formal collaboration between the V&A and the RCM that was funded by an award from the Arts and Humanities Research Council through the Knowledge Transfer scheme. The project, christened the ‘Listening Gallery’, was conceived with two phases.18 The first phase was focused on integrating music within the temporary V&A exhibition Baroque 1620–1800: Style in the Age of Magnificence (April-July 2009).19 Giulia Nuti, the Research Associate for the ‘Listening Gallery’ project, in liaison with the Baroque curatorial team at the V&A and staff at the RCM, explored the potential for using existing recordings and the making of new recordings. In total 29 pieces were chosen. Twenty-four new recordings were made by staff and students of the RCM, and three commercial recordings of major Baroque orchestral works were also included in the exhibition. The recordings were delivered ambiently in five different zones within the exhibition through directional speakers. In addition, two further recordings were added to the exhibition microsite.20 Like the objects in the displays, each piece of music was given its own label, which explained the significance of the recordings. This not only gave the music object-like status, it also served to promote the website where visitors were able to download the recordings in full.21

Evaluations demonstrated an overwhelmingly positive response to the music from the visitor’s point of view. However, the Baroque exhibition phase also highlighted valuable lessons about the challenges of delivering high quality ambient recordings throughout the temporary exhibition space, especially given the limitations of using the existing available hardware. These findings directly informed the planning for the medieval and Renaissance phase of the ‘Listening Gallery’ project.

The incorporation of music within the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries was partly motivated by a desire to broaden accessibility and to enhance visitor engagement. The initial concept was to use pre-existing commercial recordings of period music that could help visitors to imagine the medieval and Renaissance worlds and to convey emotion and feeling. Music was also envisaged as part of a strategy to communicate the overall theme of a room and to signal changes between them; underlining for example, the shift from a devotional focus in one gallery to another focussed on noble life. At the same time, two of the most significant pre-1600 European instruments in the V&A’s collections, a harpsichord made in Venice by Giovanni Baffo and a lute-back by Laux Maler, one of the most prestigious lute-makers in 16th-century Italy, had been selected for the new displays.22

These instruments too provided a natural opportunity for incorporating music directly connected to objects in the galleries, as they had done in the At Home in Renaissance Italy exhibition.23 It was only as the partnership with the RCM developed, and research progressed, that multiple connections between the displays and music became clearer and the possibilities for seriously integrating music into the displays multiplied.

Decisions about which pieces of music to select were governed by a series of overarching principles that informed the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries project as whole. The concept team felt strongly that the musical presence should represent different areas of Europe; the broad timeframe covered in the galleries; and pieces created for both sacred and secular contexts. This meant that recordings would need to be distributed reasonably evenly throughout the galleries; it was felt that each of the ten rooms should have at least one audio point. The chronological range of the pieces of music was discussed at length and it was decided not to include any music that predated 1000. This was primarily an acknowledgement of the strengths of the V&A’s collections since there were only a comparatively small number of objects from the period AD 300–1000 and none of the displays in the gallery that contained these objects had a strong connection with music. These criteria helped the ‘Listening Gallery’ project team at the RCM begin to assemble a large body of possible pieces of music from which a final selection could be made by the Listening Gallery Advisory Group and the concept team at the V&A.

The final choice of pieces was underpinned by rigorous musicological research: the recordings had to follow the performance practices of the time and the instruments used in them had to be either originals or faithful copies. For these reasons, many of the pieces used in the galleries are new recordings made at the RCM by staff, students and professional performers. However, where large numbers of singers or musicians would have been required, existing high quality recordings were used. The intention was not to offer a linear history of medieval and Renaissance music, or even a coherent musical narrative reflecting chronological developments (as can be found, for example, at the Musée de la Musique in Paris). Rather, the aim was to provide moments where visitors could encounter music at a small number of suitable points throughout the galleries.

In practice, the final selection was also influenced by more mundane factors. Evaluation of audio provision in the V&A’s British Galleries demonstrated that audio-tracks were less effective without a strong connection to immediately adjacent objects or displays.24 The implication of this was that the music chosen for each audio-point would need to relate to objects that visitors could see from the seat.

Music can be delivered to exhibition spaces in numerous ways and, after lengthy discussions, it was decided that delivering audio via small touch-screens and headphones for the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries would be the most appropriate method and offered several very practical benefits. In the first place, this would allow visitors to choose whether or not to engage with the music content, as ambient audio is not universally appreciated by visitors or gallery staff, particularly in permanent displays. Secondly, the fixed audio-point approach has been tested and evaluated over a number of earlier gallery projects, allowing the Museum to develop and refine the approach with confidence. In addition to these practical concerns, the project was committed to obtaining recordings of the highest quality and using handsets with poor sound reproduction (a type used elsewhere in the V&A at that point), would have been counter-productive. Headphones would provide visitors who chose to listen with a reasonably high sound-quality and an immersive, personal experience. Finally, 14 audio-points were created, at least one located in each of the ten main Medieval & Renaissance Galleries. Each consists of a small touch-screen computer built into a bench, and headphones, offering visitors a number of options.

Although the galleries, and the audio-points, are arranged in a loosely chronological sequence, few visitors will encounter the displays in their entirety in this way during a single visit. The first audio-point in chronological order is in Room 8, ‘Faiths & Empires 300–1250’, at the heart of the ‘Great Churches and Monasteries 1000–1250’ subject display. The recordings here relate to the Great Monasteries theme and include sung prayers written on the leaves of choir-books in an adjacent display. The last is Room 62, ‘Splendour & Society 1500–1600’ and includes the latest recordings in the project; music related to the surrounding displays about the Mannerist style and the patronage of the Medici family in Florence during the 16th century.

Many of the musical tracks in the galleries are introduced with a short spoken commentary, providing a brief context to the piece of music. These commentaries, lasting no more than a minute and a half, help reinforce the connection between the music and the object or display to which it relates. Several of the pieces of music selected for the project are quite long and so, in the version used in the galleries, it was decided to fade them out after two to three minutes. This was partly a response to visitor research about optimum length but also to ensure a reasonable turn-over in use at busy times. However, all the recordings made specifically for the project are available online via the V&A’s website.25 Here visitors can access the full recordings and listen to the pieces in their entirety without the spoken commentary provided in the galleries. While each piece of music and its commentary (and each of the fourteen audio-points) stands alone, collectively they give a real sense of the richness, development and diversity of music in this period.

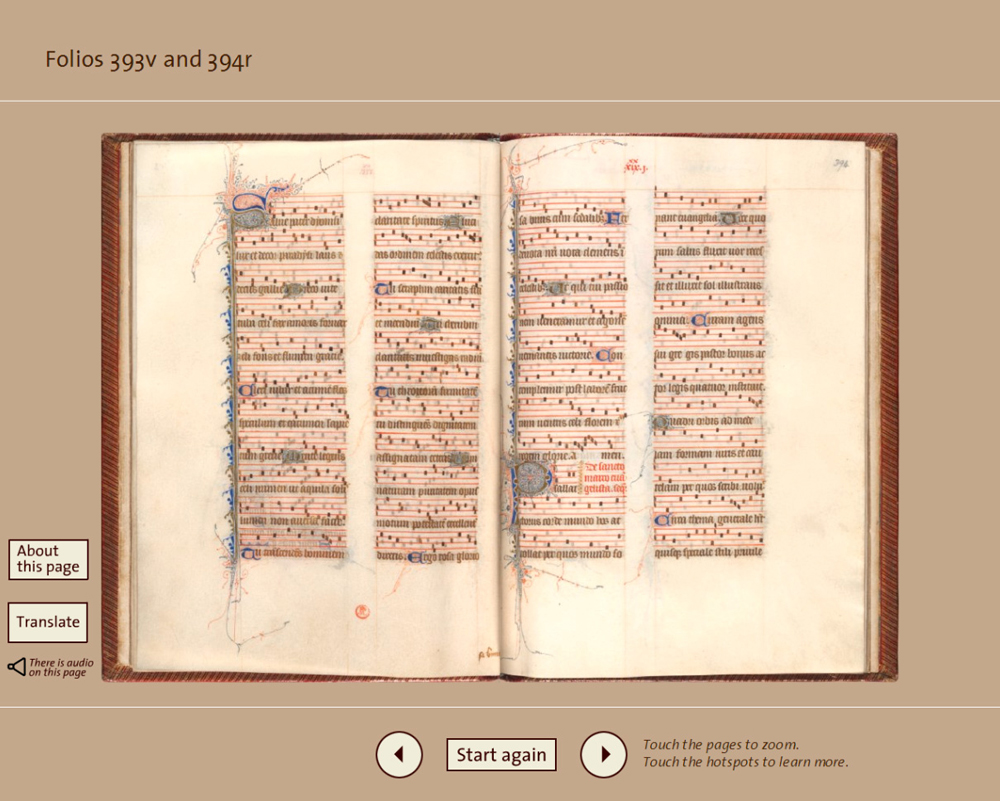

A key part of the new audio-points was the new touch-screen interface. This was specifically developed in order to give visitors (and the Museum) greater control than was previously possible using manual controls. The touch-screen allowed details of the objects to be used as attractor screens both to draw visitors to the audio-point, and to reinforce the connection between the pieces of music and the objects in the galleries (figs 4 and 6). It also allowed a transcription and translation of the words to be provided.

In what follows, the rationale for connecting particular pieces of music with specific objects is explored through a brief overview of three case studies. They each represent three broad categories of connections that were made in the new galleries between music, subjects and objects. The first includes objects with musical notation, whether service books for churches or private devotion, or objects with short inscriptions. The second relates to musical instruments, incorporating actual instruments as well as depictions of them. The final category is a broad one, incorporating objects which have a contextual connection with specific pieces of music that is not immediately obvious from appearance alone. For example, altarpieces now in the Museum’s collections once belonged in church contexts where music would have been performed as part of the liturgical calendars. In other instances, themes such as hunting or courtly love were represented as strongly in music and poetry as they were in the visual or decorative arts.

Musical notation

Case Study 1: A missal from the Abbey of Saint-Denis, Paris

This missal, made for use in the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis in Paris in 1350, is one of the most beautiful and historically important manuscripts in the National Art Library’s holdings at the V&A.26 The book contains exquisite examples of 14th-century illumination and it was primarily for this reason that the Saint-Denis Missal was originally acquired by the Museum. One of the central aims of the redisplay of the galleries was to set art and design within a more meaningful cultural context for visitors and the benefits of including a recording of the music preserved on the Missal’s pages were evident. The Missal is a key object in Room 9, ‘The Rise of Gothic 1200–1350’, where displays focus on the origins and characteristic elements of the Gothic style in Paris, and its development as it was adopted across Europe.

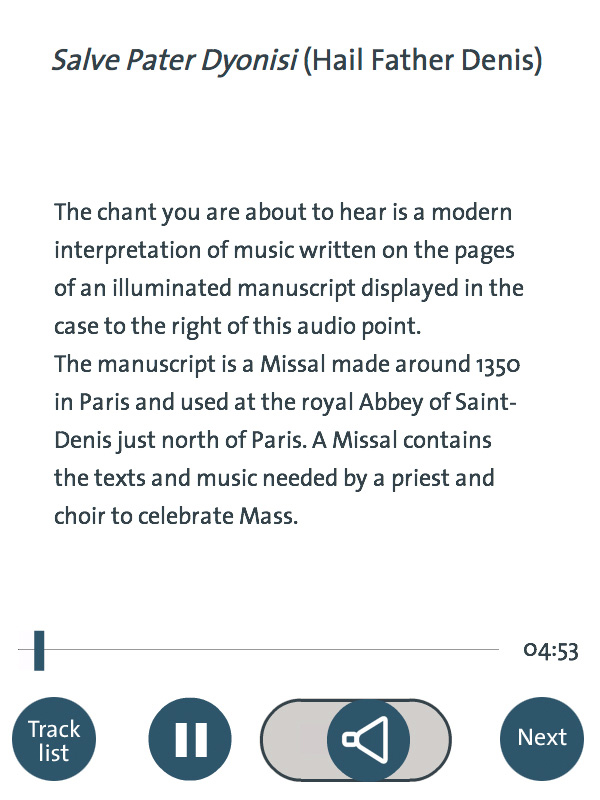

Interpretation of this object drew on existing research by Professor Anne Robertson, who has studied the notation for the chants or prayers in the Missal and other service books of Saint-Denis. However, the music itself had not previously been recorded.27 Robertson’s work focussed the project’s attention on one particular chant, ‘Salve Pater Dionysus’ (Hail Father Dionysus), which would certainly have been performed in the Abbey on the feast day of St Denis (the patron saint of France). Along with several other pieces, this chant was performed and recorded in a local church by students from the Royal College of Music with professional singers under the direction of Jennifer Smith.28

Audio: Salve Pater Dionysus (3 mins 41 sec)

The Saint-Denis Missal is now displayed in its own case with a touch-screen page-turning interactive alongside it (see fig. 3 above), that also allows the visitor to listen to the music written on the opening of the book in front of them, underlining both the original purpose of the book and the sacred context in which it was used. The music recording is also available via the audio-point located in a central gallery seat, which faces a display of illuminated stained glass from Gothic churches. Observation and tracking studies elsewhere indicate that most visitors will not use both pieces of interpretation, so in this case repetition is an effective strategy.29

To ensure that both secular and sacred music were represented,the audio-point in the seat (see fig. 4 above) also included pieces of music that were performed for courtly entertainments, reflecting nearby displays about knighthood, heraldry and chivalry - the more secular side of the Gothic style. Visitors can listen either to the 14th-century Lamento di Tristano (The Lament of Tristan), or a faster-paced, more energetic and complex piece called La Rotta, both of which relate to a popular chivalric-romance story of the period. Located in the same gallery is a vast Italian quilt on which fourteen scenes from the legend of Tristan and Isolde are illustrated.30 In this case, pre-existing high quality recordings were used.31

The majority of recordings in the ‘notation’ category related to manuscripts from monastic or ecclesiastical contexts, predominantly individual leaves. However, there were two notable exceptions: the first is a vast, complete Florentine choirbook made around 1380 for the Camaldolese order. The second is an extremely rare serving knife with a broad-blade that was inscribed on both sides with notations dated to about 1550.32

The pointed end of the knife was designed to skewer meat or bread, which could then be offered to a fellow diner. One side of the blade carries an inscription and notation related to a sung blessing before a meal, while the other side of the blade is decorated with a sung thanksgiving for afterwards.**33**The recordings made of the pieces on this knife demonstrated, for the first time, that this music was not simply decoration but could actually have been performed. The serving knife recordings were used as an integral part of a touch-screen interactive about the Renaissance home, while the serving knife itself was included in a nearby display about dining. This interactive also included recordings of domestic music-making, linked to a number of musical instruments on display.

Musical instruments

Case Study 2: A Harpsichord made in Venice by Giovanni Baffo

Though relatively few in number, the musical instruments that are displayed in the new galleries are all of outstanding importance. For example, a harpsichord made by Giovanni Baffo is one of the very finest that survive from the 16th century.34

Its lavish decoration includes fashionable classical motifs and half-moons; the crest of the wealthy Florentine Strozzi family. Indeed, like most instruments in the V&A’s collections, it was acquired because of the superlative quality of its rich and elaborate decoration. The harpsichord, once displayed in the musical instruments gallery, now forms part of a subject that explores both the furnishing of the Renaissance interior and the social activities and rituals that took place within the home. The first harpsichords were made in Venice at the beginning of the 16th century and the instrument became increasingly popular within wealthy Italian households as the century progressed, reflecting a proliferation of domestic music-making.35

Two recordings were made to accompany the harpsichord in the gallery, giving visitors both an impression of the sound of the instrument and a feeling for the type of music produced by amateur musicians within the home. The first, Venetiana Gagliarda (Venetian Galliard), published in Venice in 1551, is an instrumental dance and a type of music that might be performed on a social occasion at home, rather than for a more formal occasion at court or in a grander setting.

Audio: Venetiana Gagliarda (1 min 6 sec)

Passemezzo di nome antico (Passemezzo in the old style) is also a dance, one that would usually have been improvised on the bass line. It was first written down in 1586 by Marco Facoli, a Venetian-born composer who flourished in the late 16th-century. The musical notation for Passemezzo di nome antico is preserved in a manuscript in the library of the RCM, an exceptional example of a complex piece of solo music written at length in a manuscript.36 The style of composition of the piece is such that the right hand carries the melody and the left hand the rhythm of the dance. The recording, made for the project by Giulia Nuti, is the first to have been made of this piece.37

Although the Baffo instrument has been played in living memory, it is no longer in playing condition. The recordings for the gallery used an Italian harpsichord, made around 1678, and owned by the RCM. This was not ideal in some ways, as the RCM’s harpsichord, attributed to Onofrio Guarracino, not only dates to around one hundred years later than the Baffo harpsichord, it is Neapolitan rather than Venetian. On the other hand, alongside Venice, Naples was a major harpsichord producing centre in Italy during the 16th century. Moreover, there are very few harpsichords made before 1600 that are in playing condition, and none are in original condition, having been adapted subsequently. Therefore, while it is sadly the case that the sound of a 16th century Venetian harpsichord can no longer be heard or recovered, the recordings made for the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries are arguably as close as it is possible to get today.

It was important to the galleries project to cover as broad a geographical reach as possible which was provided by a lute instrumental by Hans Neusidler, first published in Nuremberg in 1536 – a piece of music that would have been performed in a northern Renaissance interior.38

Audio: Washa mesa, Der Hupff Auff, Gassenhauer (1 min 57 sec)

As part of the project, some additional short recordings of unaccompanied instruments were made to augment the online catalogue record of objects that were decorated with representations of instruments. A ceiling formerly in Casa Maffi, Cremona, painted around 1500, provides a good example of an object where representations of musical instruments are an important part of the iconography.

The decoration of the Casa Maffi ceiling includes the Nine Muses, seven of whom are depicted holding musical instruments such as the viol, organ, trumpet, double-flute, trumpet and tambourine.39

Medieval and Renaissance instruments, such as the viol, shawm, sackbut and gittern, are hardly commonplace in modern music, and their distinctive qualities and timbre are unfamiliar to the majority of today’s museum visitors. The short recordings of instruments were intended to expose visitors to the distinctive sound that each instrument makes and to evoke a different world.40

Audio: Medieval and Renaissance instrument - The Shawm (15 secs)

Audio: Medieval and Renaissance instrument - The Sackbut (11 secs)

Audio: Medieval and Renaissance instrument - The Harp (23 secs)

Audio: Medieval and Renaissance instrument - The Gittern (18 secs)

Contextual connections

Case Study 3: A tapestry with scenes of a boar and bear hunt, about 1425–30

This category of connections between objects and music is the most diverse and the most numerous in terms of the recordings that were made. Some of the recordings were chosen because they related to specific events depicted on an object, such as Andrea Gabrieli’s Asia Felice (Joyful Asia), a madrigal composed in 1571 for the official celebrations of the Venetian victory of the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Lepanto, an event also depicted in a German broadsheet of the same year.41 However, most recordings reflected the themes depicted on an object, or evoked the context to which the objects once belonged. A large tapestry depicting hunting scenes is the dominant object in ‘Gallery 10a’, Noble Living 1350–1500 and provides a representative example (fig. 9). **42**The dominance of this object in the room dictated that it was the most obvious point of inspiration for the music. Two pieces were chosen to reflect the themes of hunting and courtly love, both of which are depicted in the tapestry and the wider displays within the room.

An anonymous 14th-century caccia, Seghugi a corta e can per la foresta (Hounds at Court and Dogs in Forest), was chosen to underscore the hunting theme.43 Caccia is Italian for ‘hunt’, or ‘chase’, and represents one of the principal musical forms of the 14th century. Caccie reflected the popularity of hunting cultivated by the nobility at that time, reflected in the tapestry and much of the literature and visual arts of the period. Like images of hunting scenes in visual arts, the words of caccie are also often allegorical, amatory texts. Both literary and musical elements contribute to the definition of a caccia. The words of Seghugi a corta e can per la foresta are extremely realistic: throughout the song the words describe, and evoke, barking dogs, hunters shouting, horns calling, and storms. Bears and foxes also feature. Musically, the caccia consists of two voices in canon at the unison (in melodic imitation at the same pitch), creating a chase between the two voices. There is also a composed third part, which is not part of the canon and is made up of long notes. In this recording made for the project, the instrumental third part was played on a lute.

O rosabella, a piece by Johannes Ciconia (around 1370 - 1412), was chosen to represent courtly love. Ciconia was a Franco-Flemish composer, active principally in Italy. More music, with more stylistic variety, by Ciconia survives than by any other composer active around 1400. O rosabella was chosen partly because it is one of the most popular, beautiful and remarkably forward-looking ballatas of the period to have survived, but also because it is representative of the type of song that was written for the enjoyment of the elite courtly circles and probably performed by professional male singers. The piece was recorded with two male voices and a lute, played with a plectrum, as was the practice in the 14th century.

Audio: O rosabella [extract](2 mins 32 sec)

Conclusion

Although music has great potential for creating atmosphere, communicating feeling and stimulating visitors’ emotions, reproduction in a museum setting inevitably carries limitations. The interaction between players, instruments and audiences, or the excitement and physicality of a live performance, are difficult to communicate through recordings alone. A summative evaluation of the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries completed in 2011 showed that a high percentage of users engage with the audio-points, a strong indication that they are valued by visitors.44 However the evaluation had a wide remit and of necessity there was no scope to explore visitors’ responses to the music in detail. The precise impact of each audio point and specific pieces of music on visitors’ engagement with individual objects and displays requires further research. How strongly do visitors make a connection between objects, displays and the piece of music? Does the music enhance visitors’ engagement with the display and deepen their understanding of it? What impact does the music have on peoples’ overall perceptions of the medieval and Renaissance periods, which visitor research suggests are usually characterised as difficult, distant and remote? No matter how thoughtfully the pieces were selected or how carefully the audio-points were juxtaposed with the displays, prior knowledge and individual experience will, of course, play a significant role in shaping each visitor’s response.

Other aspects of the project are easier to quantify and assess with confidence. Those institutions and individuals involved in the Listening Gallery project benefited in numerous ways. Over forty students at the Royal College of Music had the opportunity to study, rehearse and perform music that usually falls outside of the traditional curriculum (fig. 10). The process of performing, recording and working with professional musicians gave the students valuable experience for their future professional careers. The V&A obtained over 50 high quality recordings of pieces music, 21 for the Baroque exhibition, and 30 for the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries. For the latter these pieces of music had direct and tangible connection with objects in the displays which the Museum had neither the expertise nor resources to obtain independently. The project also made a significant contribution towards enriching curatorial knowledge of a number of objects in the collection. The fruits of this research have been made available to an international audience through the physical displays and associated online content, as well as through published articles and conference papers.

The ‘Listening Gallery’ project has established a model and approach that has the potential to be refined and applied to future projects at the V&A and other museums. The increasing ownership of smartphones and MP3 players is rapidly increasing the options for museums to deliver music in gallery spaces and the number of ways in which visitors can choose to engage with it. Importantly, the Museum has the option to use all of the recordings made by the RCM in future online and digital applications and to further extend the reach and impact of the project.

Acknowledgements

The ‘Listening Gallery’ project would not have been possible without the contributions of numerous people. In particular, thanks are due to: the students from the RCM who participated both in performances at the V&A and recordings at the RCM; Jakob Lindberg, Jennifer Smith, Bill Lyons and Terence Charleston at the RCM who led rehearsals, coaching sessions, performances and who also contributed research; Aaron Williamon, Ashley Solomon, Paul Banks, David Burnand, Jenny Nex and Lance Whitehead for scholarly input and shaping the project; Seb Durkin and Jon Rule for their help in making the recordings; Flora Dennis and Clifford Bartlett for advice. At the V&A the following people were also key: Carolyn Sargentson and Chris Breward; Eric Bates for developing the interface and hardware used in the galleries; Peter Kelleher and Maike Zimmermann for documenting the project with film and photography; Andrea Carr for building web-content; Meghan Callahan for translating the Latin and Italian words for many of the pieces; James Yorke for advice about the musical instruments collection at the V&A and the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries project team including Glyn Davies, Kirsten Kennedy and Peta Motture

Endnotes

-

Victoria & Albert Museum. Creative Research, ‘Medieval and Renaissance Galleries: Front-end research, May 2003’; Victoria and Albert Museum. Morris, Hargreaves, McIntyre, ‘Engaging or Distracting – Visitor Responses to Interactives in the V&A British Galleries, June 2003’; Victoria & Albert Museum. Creative Research, ‘Summative Evaluation of the British Galleries, September 2002’. Accessed May 31, 2012. ↩︎

-

Victoria and Albert Museum. Fisher, Susie. ‘What do Medieval and Renaissance really mean to people? – Front End Qualitative Research, December 2002’. Accessed May 31, 2012. ↩︎

-

Falk, J. H. and L. D. Dierking. The Museum Experience. Washington, DC: Whalesback Books, 1992; Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly and Kim Hermanson. ‘Intrinsic motivation in museums: why does one want to learn?’ in The Educational Role of the Museum, edited by Eilean Hooper-Greenhill. London: Routledge, 1999; Davies, Jessica and Howard Gardener. ‘Open Windows, Open Doors’, in The Educational Role of the Museum, edited by Eilean Hooper-Greenhill. London: Routledge, 1999. ↩︎

-

Victoria & Albert Museum. Creative Research, ‘Summative Evaluation of the British Galleries, September 2002’. Accessed May 31, 2012. ↩︎

-

Music in museums has not been the focus of detailed study or writing. Musical instrument museums are an exception. See, The International Committee of Musical Instrument Museums and Collections guidelines on interpreting musical instruments: Birley, Margaret, Heidrun Eichler, and Arnold Myers. Voices for the Silenced: Guidelines for Interpreting Musical Instruments in Museum Collections. 1998. Accessed 31 May, 2012. ↩︎

-

Museum of Musical Instruments, Brussels. Accessed May 31, 2012. Malou Haine ed. Musical Instruments Museum – Visitor’s Guide. Belgium: Mardaga, 2000; The Musée de la musique, Paris, has recently been redisplayed: The Musée de la Musique. Accessed May 31, 2012. See also de Visscher, Eric. ‘From Instrument cabinet to Museum of Music’ in Musée de la Musique, by Philippe Bruguière et al, 12–19. Paris: Somogy Art Publishers, 2009; Carla Zecker wrote about the older displays in: Zecker, Carla. ‘Musical Instruments, Glass Cases and Headsets: Sound and Sensation in France’s Museum of Music’ in Music, Sensation and Sensuality: Cultural and Critical Musicology, edited by Linda Austern, 245–63. New York: Garland Press, 2002. ↩︎

-

Horniman Museum, London. Music Gallery. Accessed May 31, 2012. ↩︎

-

Austern, Linda. ‘Introduction’ in Music, Sensation and Sensuality: Cultural and Critical Musicology, edited by Linda Austern. New York: Garland Press, 2002: 3. ↩︎

-

Thanks to Kylea Little, Keeper of History at the Discovery Museum for providing information about the Great City exhibition. ↩︎

-

Bray, Xavier (curator). The Sacred Made Real - Spanish Painting and Sculpture 1600–1700. London: The National Gallery, 2009. ↩︎

-

Taylor, John (curator). Journey through the Afterlife – Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead. London: British Museum, 2010/2011. ↩︎

-

Romanek, Devorah(curator). Akan Drum. London: British Museum, 2010. For details of the soundtrack: The British Museum. ‘Akan Drum: Playlist’. Accessed May 31, 2012. ↩︎

-

This statement is based on unpublished summative evaluation of the following British Museum special exhibitions: Taylor, John (curator). Journey through the Afterlife – Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead. London: British Museum, 2010/2011; Romanek, Devorah (curator). Akan Drum. London: British Museum, 2010; McDonald, Mark (project manager). The Sámi Magic Drum. London: British Museum, 2009; McDonald, Mark (project manager). Gamelan – Music of Java. London: British Museum, 2009. ↩︎

-

Dennis, Flora; Marta Ajmar-Wollheim (co-curators). At Home in Renaissance Italy. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 2006. ↩︎

-

Dennis,Flora. ‘Music’. In At Home in Renaissance Italy, edited by Marta Ajmar-Wollheim and Flora Dennis, 228–243. London: V&A Publications, 2006. ↩︎

-

The recordings were made by Lucia Sciannimanico, mezzo-soprano; Valerio Losito, violin and lyra da braccio; Marta Graziolino, harp; André Henrich, lute, Giulia Nuti, harpsichord. ↩︎

-

Victoria and Albert Museum. ‘At Home in Renaissance Italy: Music’. Accessed June 1, 2012. ↩︎

-

Royal College of Music. ‘The Listening Gallery’. Accessed June 1, 2012. ↩︎

-

Snodin, Michael; Joanna Norman (co-curators). Baroque 1620–1800 – Style in the Age of Magnificence. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 2009. Llwellyn, N. and M. Snodin, eds. Baroque 1620–1800 – Style in the Age of Magnificence. London: V&A Publications, 2009. ↩︎

-

Victoria & Albert Museum. ‘Baroque 1620–1800 – Style in the Age of Magnificence: Music’. Accessed June 1, 2012. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Lute, LauxMaler, about 1540. Museum no. 194:1, 2-1882; Harpsichord, Giovanni Baffo, 1574. Museum no. 6007-1859. ↩︎

-

Dennis, Flora. ‘Music’ in At Home in Renaissance Italy, edited by Marta Ajmar-Wollheim and Flora Dennis, 228–243. London: V&A Publications, 2006. ↩︎

-

Victoria & Albert Museum. Fujishiro, Satoko. ‘Evaluation of Audio Programmes and Film Rooms in the British Galleries, August 2005’. Accessed June 1, 2012. ↩︎

-

Victoria and Albert Museum. ‘Medieval Music 1000–1400’.; Victoria and Albert Museum. ‘Renaissance Music 1000–1400’. Accessed June 1, 2012. ↩︎

-

Missal from the Abbey of Saint Denis, 1350. Museum no. MSL/1891/1346. See also, Watson, Rowan. Illuminated Manuscripts and their Makers. London: V&A Publications, 2003: 90–91. ↩︎

-

Robertson, Anne. The Service-Books of the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis: Images of Ritual and Music in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Clarendon, 1991. ↩︎

-

A short film documenting the recording of Salve Pater Dyonisi can be viewed online. Victoria and Albert Museum. ‘Music from a missal from the abbey of Saint Denis’. Accessed June 1, 2012. Recordings related to individual leaves from other service books were also made: leaf from a choirbook, about 1250. Museum no. 1517; leaf from a choirbook, about 1250. Museum no. 1519; Leaf from a choirbook, later 12th century. Museum no. 244.2 A short film about these recordings can be viewed online. Victoria and Albert Museum. ‘Music from choirbook leaves’. Accessed June 1, 2012. ↩︎

-

This is borne out by a number of studies at the Victoria and Albert Museum and elsewhere. Victoria and Albert Museum. Morris, Hargreaves, McIntyre. ‘Engaging or Distracting – Visitor Responses to Interactives in the V&A British Galleries, June 2003’. Accessed 1 June, 2012; Victoria and Albert Museum. Creative Research. ‘Summative Evaluation of the British Galleries, September 2002’. Accessed 1 June, 2012. ↩︎

-

The Tristan Quilt, about 1360–1400. Museum no. 1391-1904. ↩︎

-

From the CD ‘A L’Estampida - Medieval Dance Music’. Performed by: Dufay Collective. Label and release date: Avie, 2004. ↩︎

-

Choirbook, Florence, about1380. Museum no. MSL/1868/5836. Notation knife, about 1550. Museum no. 310-1903. A short film about the recording of the notation on the knife can be viewed online. Victoria and Albert Museum. ‘The notation knife’. Accessed June 1, 2012. ↩︎

-

Dennis, Flora. ‘Scattered Knives and Dismembered Song: Cutlery, Music and the Rituals of Dining’ in Renaissance Studies XXIV (2010): 156–84. ↩︎

-

Harpsichord, Venice, 1574. Museum no. 6007-1859. ↩︎

-

Dennis, Flora. ‘Music’ in At Home in Renaissance Italy, edited by Marta Ajmar-Wollheim and Flora Dennis, 228–243. London: V&A Publications, 2006; Dennis, Flora. ‘Medieval and renaissance music’. In Medieval and Renaissance Art – People and Possessions, edited by Glyn Davies and Kirstin Kennedy, 296–297. London: V&A Publications, 2009. ↩︎

-

Facoli, Marco. Passmezzo di nomeantico. London, Royal College of Music, MS 2088, late 16th century. ↩︎

-

A short film about the harpsichord recordings can be viewed online here. Victoria and Albert Museum. ‘Passemezzo di nomeantico’. Accessed June 1, 2012. ↩︎

-

The piece, ‘Washa mesa – Der Hupff Auff – Gassenhauer’, is from a book by Hans Neusidler published in Nuremberg in 1536, Ein Newgeordnet Kunstlisch Lauteenbuch, In zwen theyl getheylt. ↩︎

-

Ceiling from Casa Maffi, Via Belvedere, Cremona, about 1500. Museum no. 428-1889. ↩︎

-

These short recordings were made under the direction of William Lyons. The shawm was played by Sarah Humphries, the gittern by Arngeir Hauksson and the harp by Jon Banks. ↩︎

-

True Likeness of the beheaded Turkish officer Ali Bassa, woodcut, about 1571. Museum no. E.912-2003. ↩︎

-

Tapestry with scenes of a Boar and Bear Hunt, about 1420–1425. Museum no. T.204-1957. ↩︎

-

Anonymous 14th century caccia, Seghugi a corta e can per la foresta. Florence: Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Panciatichiano 26, fol. 99 (3/2); London: British Library, Additional 29987, fol. 77v (3/2). ↩︎

-

Victoria and Albert Museum. Fusion Research and Analytics. ‘Case Study Evaluation of FuturePlan: Medieval and Renaissance and Ceramics Galleries Phase I and II, March 2011’. Accessed June 1, 2012. ↩︎