Abstract

Encounters in the Archive will be shown in the Tapestries Court at the V&A in 2012 as part of Transformation and Revelation, a series of displays produced by the Theatre and Performance Department in collaboration with the Society of British Theatre Designers. Funded by a research grant awarded by London College of Fashion, and produced with the support of Theatre and Performance and the Research Departments at the V&A, the project was selected for the V&A after it appeared in an earlier guise in Cardiff at the National Exhibition of Theatre Design 2011. The film has also been screened at the PQ2011, Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space as part of the OISTAT History and Theory Commission.

Introduction

This paper discusses and reflects upon aspects of the practice-based research project led by the author and titled Encounters in the Archive, which resulted in a 17 minute film depicting artist/researcher interactions with theatre costume and other archived, difficult to access objects in the V&A. The paper highlights the current lack of discourse on theatre costume, which prompted the Encounters in the Archive project and its specific methodological approach.1 It shows how the camera can be used as a mechanism for enquiry, in this case via the expert filming and editing of film-maker Netia Jones. 2 Finally, it focuses on the responses to particular costumes in the V&A’s Theatre and Performance Collections by three expert participants, and shows how such interactions can help to articulate the performativity of costume, retained in their collected and conserved state as fragments of past performances.

Ambiguities and absences, discourse on costume

The Actor in Costume (2010), by Aofie Monks, is the only recent book to explore the centrality of costume to live performance reading the actor-in-costume from a cultural and performance studies point of view. Indeed, such is the vacuum in discourse on costume that it has been filled by re-publications of old classics, such as James Laver’s Drama - Its Costume and Décor (1951) and Costume in the Theatre (1964), which are limited in approach. A historian of art, dress and theatre, Laver dealt exclusively with historical material. More recent publications do explore the subject from the perspective of Museum collections, such as Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes (2010), a collection of essays written to accompany the eponymous V&A exhibition and edited by museum curators Jane Pritchard and Geoffrey Marsh. The costume within the museum context is afforded protection, conservation and value within an institutional context, while also providing each costume/object with a carefully researched and constructed history. As museum object, the costume becomes precious, guarded and also, by necessity, removed from the notion of performance.

Even in the broad field of scenographic discourse the costumed, performing body is sited, somewhat ironically, in the background. The audience’s relationship to the performance space, to sound and to lighting is now being debated in some detail in critical discourse on theatre, particularly as these spatial and experiential concerns connect with the more established academic field of architecture. This is particularly evident in publications such as Performance Design (2008), edited by architects and scenographers Dorita Hannah and Olav Harsolf, and in Arnold Aronson’s Looking into the Abyss: Essays on Scenography (2005). Yet, in this debate the sensory, visual presence of the dressed body of the performer remains conspicuous by its absence. This seems particularly odd, given that an audience’s engagement with the performance is through the performer’s body - at the centre of the scenographic construct.

The field of dress and fashion studies has also developed enormously, particularly since Elizabeth Wilson’s seminal Adorned in Dreams (1985). Scholars and curators such as Lou Taylor, Amy de la Haye, Christopher Breward, Caroline Evans, Joanne Entwistle, Claire Wilcox and Judith Clark have together banished unequivocally the taint of frivolity that kept dress invisible as a scholarly research subject for much of the twentieth century. Over the last twenty years, these authors have exposed dress, and occasionally costume, as a complex historical, cultural, political and social construct that articulates the body and identity. They have shown how it can be read and decoded as a visual sign, understood as shared, embodied and cultural memory - aspects that have also inspired visual and performance artists.

The idea that dress carries memories and histories and that it acquires individual qualities through personal interactions with its wearer and viewers was of particular relevance to the Encounters research project. This idea was central to A Family of Fashion, The Messels: Six Generations of Dress (2010), in which de la Haye, Taylor and Thompson write about Jill Ritblat (who donated 300 high society dress outfits dating from 1964–98 to the V&A) and her relationship with her garments: she ‘began to feel affectionate towards them, as towards old friends’. During one of the ‘encounters’ orchestrated as part of this research project, curator Janet Birkett too spoke about the costumes in her care in terms of levels of familiarity and intimacy, commenting that ‘some are friends, others merely acquaintances’.3 Another of the key conceptual drivers to this research project was the notion that the absent body and the traces it leaves behind in the lived in and performed in costume are not only memories but acquire agency in the ‘dialogue’ with an engaged viewer in the here and now. In an‘encounter’ discussed at length below, Amy de la Haye spoke about how ‘lives lived and performances performed’ were embodied in the costume that stood in front of her. By gathering together these perceptions of the material object from a unique, informed, engaged and personal perspective, the film enables a cumulation of specific insights which can begin to address the absence of discourse on costume.

In the field of performance studies the body has become increasingly prominent, building on phenomenological aproaches and on theories initially explored by sociologists Chris Shilling and Helen Thomas. The more recent work of cross-disciplinary philosopher and cognitive scientist Alva Noë, whose sense that ‘the world makes itself available to the perceiver through physical movement and interaction’ also profoundly influenced the methodological approach of the Encounters project.4 This is particularly evident in the staging of the encounters, which privileged responses inspired by a spontaneous and close-up dialogue with the object, and downplayed responses couched primarily in intellectual terms, informed by disciplinary rigour. In the absence of the body of the performer, the ability to touch, move and view the object close up elicited responses from participants that helped to articulate the performative qualities of the objects.

Without its own scholarly discourse, theatre costume is subsumed into the performer’s body and its contribution to the performance, its ‘complex work’ and that of the hands that make it, remains un-remarked upon. As implied by Aofie Monks, ‘Theatre scholarship has a tendency to approach the actor as “already dressed”, or indeed “already undressed”, rather than acknowledging the complex work that costume does in producing the body of the actor.’5 The costume worn by the actor is read in theatre scholarship as integrated into the essence of the construct that is the actor-on-stage. The methodology of Encounters in the Archive proposed the costume, an archived object, as ‘undressed’ from the body of the performer, yet still in conversation with its viewer. For this reason participants to the project were all interested experts, whose work is with costume, dress, performance and artistic practice. They included costume designer Nicky Gillibrand; a specialist costume pattern-cutter, Claire Christie; fine artist working with dress, Charlotte Hodes; author and curator of dress, Amy de la Haye; photographer Paul Bevan and fashion designer and academic Darren Cabon, accompanied by postgraduate student Marios Antoniu.

The agency of costume

Little attention is drawn to costume by critics of live performance in reviews published in broadcast and printed media. Yet images of costumed performers are routinely deployed as photographic representations of the performance itself, often serving as embodiment of its visual identity. In June 2011, for example, photographer Keith Pattison was commissioned by the Young Vic to photograph the production of Government Inspector. His striking images were then used by the Theatre, as part of the advertising campaign for the performance.

They eloquently reflected the absurd quality of the performance through composition, angle, colour, lighting and environment, but largely through the visual identity - eclectic, inventive and hilarious - constructed by costume designer Nicky Gillibrand. Yet of the ten reviews that were published alongside these images, only two mentioned her name.6 Miriam Beuther, the set designer, whose work was certainly worthy of praise, seemed to absorb much of the credit for the aesthetics of the performance as a whole, her name being mentioned in eight of the articles surveyed. Given that the vivid nature of Gillibrand’s costumes was very difficult to ignore, the failure to mention her vital contribution to the show is rather puzzling. The ‘already-dressed’ actors depicted here also draw attention to the inability of theatre critics to discuss dress on stage.

Images of costumed bodies from ubiquitous productions such as Les Misérables, The Phantom of the Opera, Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake and Billy Elliot, are now permanently embedded in the collective memory, yet their designers remain largely unnoticed.

Their design work nonetheless contributed to the national and international success of these productions, woven seamlessly into the identity of the show. Assimilated into the necessary branding of the performance, the costumed body, arguably a theatrical, artistic and cultural construct, is reflective of a shared memory and understanding of dress. The costumed body can be seen as a sign, indicating specific aspects of the role of the individual performer, their presence in the show and the type of performance. Read primarily as a pragmatic sign, however useful to the narrative and to the marketing of the show, costume can be reducible, reproducible and can ultimately be taken for granted and become unnoticed. Ironically within its success lies its downfall. This project aims to reverse this process, not only in terms of encouraging research into costume,but also in terms of raising the profile of costume designers, and improving understanding of ‘the complex work that costume does in producing the body of the actor’.

The complex interaction inherent to the creative process in ‘producing the body of the actor’ on stage gives costume its unique effectiveness. The visual and material embodiment of specific ideas about the performance, and the communication of these notions in the here-and-now experienced by the audience, is arrived at through layered and nuanced process, involving several bodies, hands and eyes. Beyond the definition of the role of the actor in the play, costume can be at the very core of the process of inhabiting the performance moment. This effectiveness is communicated to a sentient, perceiving audience in the experienced and shared moment of the performance. Costume has agency as intermediary between performer and the spectator, not only through a visual response, but also a sensory one, projected via surface, colour, form, textiles, movement and weight. It draws attention to the body, by what it reveals or conceals, through fit, by the way it organizes the body’s composition and proportion. It can highlight or even generate gesture and movement. It responds to the on-stage world, created by both the space in which it moves and by the other costumed bodies it encounters there. Costumes on stage create an ongoing sensory and visual dialogue with the spectator, whose own embodied sense of what it is like to be a ‘dressed body’ comes into play, as ‘the activity of watching is an on-going physical adjustment and response to other physically present bodies.’7

The ‘work’ of the costume, is therefore vital in the creation and in the reception of performance where agency is sited in a shared visual and tactile understanding of dress, eliciting a sensory, experienced response alongside a reading and decoding of visual signs. The exploitation of shared, embodied and cultural memory that can be posited in costume plays a central role in the creation and communication of meaning in live performance. As a consequence, the crafting of the costume for performance requires both designers and makers to role-play the co-authoring, responsive audience at every stage of the creative process. The form costume takes is determined by the desire to project into the moment of the performance, as much as from a balancing act of artistic synthesis and practical concerns. Costume is inscribed with the performance from its conception. In its ideal state, while it is being conceived, it only exists for that performance, for that performer, in that particular moment in time. Separated from its context costume becomes redundant, yet as an object it is marked with a creative process which mediates between performance, its crafting, the body and the gaze of the audience. As such, a costume contains several different performances, inscribed into it through the work that made it.

Elizabeth Wilson remarks‘that garments so close to our bodies also articulate the soul’; and claims that ‘we experience a sense of the uncanny when we gaze at garments that had an intimate relationship to human beings’, implying ambiguity in the way garments no longer in use may impact upon the experience of encountering them.8 In Encounters in the Archive, it was intended to exploit the absence of the performer’s body and to articulate the performative soul in collected and archived costume through interaction with selected participants. The permeable nature of costume, its in-between state, susceptible to being appropriated and overlooked, could then be turned to an advantage as a perspective from which costume can look outwards from its unique point of view, to the complexities that it embodies, even when little is left of the performance that gave origin to it.

Filming in the archive

Among the stated aims of the V&A is the desire to inspire creativity by way of access to its collections. Encounters in the Archive investigates the nature of costume through the archive in a film-based exploration, by placing the costume-objects in dialogue with invited artists, designers and writers in ‘staged’ encounters, thus expanding in ever increasing circles the creative inspiration offered by the objects filmed in the archive. Edited down from eighteen hours of filming to seventeen minutes, it is a creative response to the experience of the archive and the interaction with the object. Netia Jones, who shot and edited the film, is a film maker and visual artist working in theatre and site specific installations, who often combines video, music and theatre using the camera as an expressive, artistic tool. This results in productions that are multilayered and profoundly visual experiences. Her recent Everlasting Light at Aldeburgh Festival in June 2011 was lauded by, amongst others, Richard Morrison of The Times in unequivocal terms: ‘Such all-encompassing artworks make what normally goes on in concert halls, theatres and galleries look tame and prehistoric’.9

The generous filming schedule enabled the capture of interactions between the invited interlocutors and the objects that had been chosen with them. The meetings between Netia Jones and myself established a methodology that applied a phenomenological approach, where the intention is:

To redirect attention from the world as it is conceived by the abstracting ‘scientific’ gaze (the objective world) to the world as it appears or discloses itself to the perceiving subject (the phenomenal world); to pursue the thing as it is given to consciousness in direct experience; to return perception to the fullness of its encounter with its environment.10

If the costume / object is a cultural construct – qualified by the context of the original performance – then, when separated from the performer and collected by the museum, its perception becomes mediated by the institution. Rather than dispensing knowledge, Encounters in the Archive seeks to immerse its participants into the experience of the moment, and to engage their imaginative responses to the one-to-one archive experience, specifically designed for each individual encounter. The unmediated costume/object, naked of interpretation, constituted a discovery in the moment of the encounter. These encounters took place within the vastness of Blythe House, which, alongside a number of national design archives, holds the V&A’s enormous Theatre and Performance archive collection. Originally built to house the Post Office Savings Bank in the early 20th century, the monumental scale and architectural style of this civic building create a convincing scenographic space for the archive. Absorbed in its environment, one perceives both the institutional protection granted to the objects that are selected for posterity through the collecting process, and the necessary exclusion and control systems that this implies.

Kate Dorney, curator in contemporary Theatre and Performance, lent her words to these shots, thus becoming the voice of the archive. The scale of the archival space resonates in her spoken list of the quantitative data by which the Theatre and Performance archive can be measured. Holding ‘sixty thousand files of Arts Council material… twenty thousand stage designs… twenty thousand pieces of costumes… three million photographs’, the theatre and performance archive is ‘the biggest collection of its kind in the world, in terms of its scope, chronologically and in its richness and complexity’, and despite the seemingly limitless space, it is ‘nearly full’.11

Engaging in an encounter that fore-grounded experience and perception, the camera itself took a subjective position, moving through the interminable corridors of shelves piled neatly with acid free boxes, and communicating the vastness of the ‘layers upon layers’ of nearly a century of collecting. Jones’ insight is that through the process of filming and editing, the moving of the camera in the space ‘interrogates the meaning of the space itself’. The corridor shots hint implicitly at the contradictions inherent in a static archive of performance,rendered vivid through Netia Jones’s editing andusing of continuously moving, overlaid backgrounds.12

In a post-project meeting on the process of filming, Netia Jones reflected that the presence of camera into the unfamiliar space of the archive increased the intensity and the focus on the here-and-now of the moment by purposefully placing the subjects and the objects under a metaphoric and real spotlight. Both the camera and the careful preparation for the encounters emphasised the qualities of the object in the moment of its discovery by the viewer.This dynamic process was intended to evoke an instinctive response, with the one-off nature of the filming process enabling these responses to be documented, and to then begin to articulate the complexity of the object that is costume through the editing process. In Netia Jones’ filming the protagonists, viewers, objects and spaces, are interwoven. Meanings are not inscribed but are revealed through interaction, in the dance-like movement that takes place through the layers of editing. In Noë’s words ‘the world makes itself available to the perceiver through physical movement and interaction’, as the camera, moving through space and gazing into the objects, immerses the audience of the film into the experience of the encounter with the object.13

The costume object / the costume subject

The invited participants were selected for their range of expertise and perspectives on dress and the body. Prior to the filmed visit to the archive, a process of identifying costumes, collected by the V&A, relating to their practice was put in place. As such, each encounter was curated while access to the archive at Blythe house was negotiated in discussion with the archivists. The participants, who had been involved in the selection process, were invited to concentrate on the object as it came into focus rather than prepare a presentation about the object. The intention was that they should gain insights specifically inspired by the object in the specific moment of encounter. If perception is a skilled activity, relying on embodied knowledge, then each individual would bring to bear their unique way of looking at and engaging with the object.

Professor Amy de la Haye, Rootstein Hopkins Chair of Dress History and Curatorship at London College of Fashion, has written extensively on fashion and material culture and Coco Chanel’s costumes. She was also, for several years, a curator of historical dress at the V&A. A highly valued international scholar in her field, she spoke in great detail about the historical and cultural context of the costumes she encountered. This contextual material however has not made it into the final edit, as the research project was not about establishing factual contexts. Instead the focus was on her responses to her first ever close-up viewing of the costume for La Perlouse in Le Train Bleu designed by Chanel for the Diaghilev Ballet in 1924.

She remarked how this knitted costume evoked the dancer as it had adapted ‘to accommodate the shape of the body’and was ‘imprinted by the wearer’. She concluded that the costume was ‘entwined with life lived and performances performed’.14 On close inspection she commented in surprise ‘it is mended all over… you’d have thought they might have got new ones’, particularly given the projection of luxury inherent to the context of this high-profile production and of Chanel’s designs, whose costumes, as Lynn Garafola has observed, appeared to the audience as if they ‘might come from her customers’ wardrobes’. 15 Yet, more than purely fashionable, prima ballerina Lydia Sokolova felt ‘quite radical’ dancing in this costume, demonstrating the integral role costume plays in the way the dancer perceives herself on stage.16 The costume here is inextricably linked to the impact of Sokolova’s dance, which would have been entirely different in a classic tutu. The effort poured into the mending of this knitted, on-stage swimsuit - to keeping it intact - may well have played a key role in the successful performances of Le Train Bleu. Making a direct comparison with Chanel’s fashion work, de la Haye comments on the quality of the knit, the colour and the proportions confirming that she had not seen ‘anything like this in [Chanel’s] fashion collection’, thus placing the garment in a quite separate category from those in Chanel’s customers’ wardrobes. ‘It is extraordinary that it really is quite a vibrant rose pink’, she had expected it to be ‘much more like everyday swimwear and it’s absolutely not, because women’s swimwear was made with machine knitted jersey or machine knitted wool’. De la Haye suggests that ‘It looks much more artisan than I’d imagined – I’d imagined it was going to be modernistic and quite a smooth knitted jersey, but it actually looks hand-knitted.’ She also notes how discretion would have determined that the cut of the vest be longer in everyday swimwear, again reflecting on the unique nature of the costume for the specific performance and performer. Thus the La Perlouse costume draws attention to itself and its wearer through not only its vibrant colour, but also the noticeable hand-knit texture, which would have been far more responsive to light and movement than a smoother machine knit, while making evident the articulation of the dancing body through adjustments in cut and proportion. In de la Haye’s words, ‘a different kind of performativity from everyday fashion’ is at work here. ‘This is the beauty of looking at the real thing, it just opens your eyes’, notes de la Haye, then, adding as an aside, ‘it must have been itchy as well’.

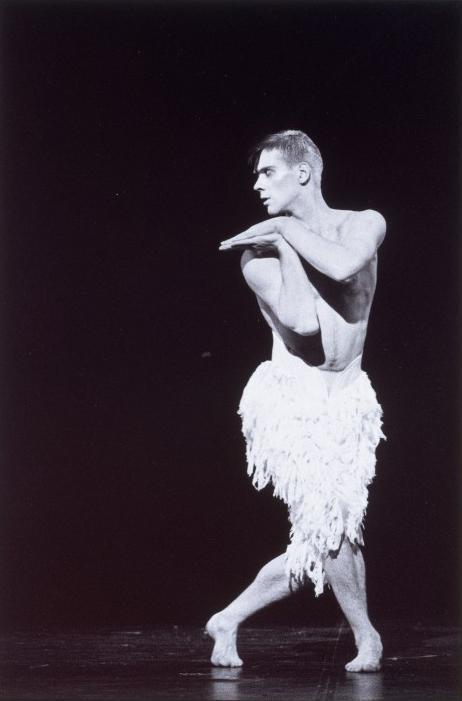

The sensory qualities, visual and tactile, that are communicated by costume are something to which Nicky Gillibrand, as a highly valued international costume designer, would also be finely attuned. On encountering The Soldier in Chout, 1921, also a Diaghilev Ballet, designed by Mikhail Larionov, Gillibrand’s first response was surprise at the ‘unbelievable amount of clothing’ to dance in, and that the layered, stiffened clothing would be ‘an absolute killer for a dancer’.17

The costume presented a combination of high-contrast, painted and appliquéd heavy cotton and buckram, including a long sleeved tunic with wired epaulettes projecting outwards from the upper arms and shoulders, a painted buckram breastplate with wired skirt, trousers, mask, wired buckram beret and ‘those giant boots!’. The dancer’s movement, inevitably, would have been choreographed around the costume and what they could do in it, rather than displaying the full articulation of the dancer’s own moving body. Whereas La Perlouse made evident the dancing body by deliberately adjusting the fashion cut of the costume, here the costume almost entirely absorbs the body into itself by extending it through space, whilst simultaneously concealing it, in wired and stiffened buckram.

As a fine artist, Larionov clearly treated this dance piece as a work of art that moves. His designs were developed intermittently over a number of years, ultimately even sharing the choreography credits with Thadée Slavinsky.18 In her encounter with the costume, Nicky Gillibrand suggests that Larinov’s hand may well have been at work even in the realisations of the costumes. Not only would it appear that Larionov carefully chose the complex combination of fabrics and painted surfaces, deliberately creating the effect he was after, but, observing closely,Gillibrand noted how the still present pencil lines, appeared as if ‘they have just been drawn on’ and gave the garment a sense of being ‘almost not quite finished’. The pencil lines mark the spacing between the bold intersecting shapes that dissect and reconstruct the body of the soldier in a neo-primitive Cubist composition. Gillibrand felt that these were ‘quite child like’. ‘I rather love the crudeness of it, it’s the beauty of it’. Looking at this costume the direct involvement of the designer was evidenced by the uncompromised boldness of the forms and lines, ‘makes me feel like the artist was involved. You kind of know what you want to it to look like, whereas costume makers tend to want to make it look beautiful. ’By visually upstaging the performer’s body, this costume serves as a means through which the designer claims authorship of the work - an authorship that extends to co-choreographing the movement. The direct intervention of the designer’s hands in the making process reinforces that sense of authorship.

The Meleto Castle costumes, dating from around 1750, were selected for Charlotte Hodes, Reader in Fine Art at the University of the Arts, London. These lack either a named ‘author’ or even any reference to a specific performance, though they would have been used for private performances.19

In encountering this costume Hodes, in whose paintings the female form is juxtaposed with complex, layered surfaces, immediately noticed the way her eye was invited to travel across and around the sides of the torso by the ‘surprisingly bold pattern’ of the embroidery. The ‘luscious’ and ‘swirling’ raised silver and gold embroidery ‘exists as its own object’ in a structured composition of enlarged scrolls and flowers, ‘resplendent’ while contrasted against the red velvet, on which it is ‘encrusted’. Hodes claims that, ‘The other wonderful contrast you have is the tight stitching, which you probably wouldn’t see on stage… you can see the directional changes of the stitching… which is very beautiful and very tightly stitched. Then you get the contrast with… the little flickery bits that are around the edge like fronds’.20

The Meleto Castle costume would have reflected candlelight very effectively, through the changing lines of the threads in the embroidery pattern, the moving, fringed, peplum pieces and the shape of the velvet garment itself which, by absorbing and reflecting the light in different ways and in different directions, emphasise both movement and structure. Notwithstanding the weighty impression of this costume, which was made on a hessian base with furnishing velvet and precious metal embroidery, the ‘swirling’ motion materialized in the raised pattern of the embroidery against the velvet, echoes the pattern and movement of baroque dance. ‘You really sense a sort of atmosphere, the music, the ambience, all that is contained within the garment’, concludes Charlotte Hodes. The relationship with space, light and movement are all embedded into this costume, which seems to be holding the dance within itself. When brought out momentarily into the light, the Meleto Castle costume maintains the spatially and historically sited performative effectiveness that shaped it.

Conclusion

The complex object that is costume - constituted through craft and performance and re-contextualised in its archived and collected state - once taken out of the necessary but forbidding acid-free archive box, can offer new ways to articulate its performative values. By placing the non-interpreted costume object in conversation with an engaged, informed and perceptive interlocutor in unmediated and uncommented upon encounters, this project has been able to draw out some key findings about costume. Amy de la Haye’s response to Chanel’s La Perlouse makes clear the relationship between costume, the body and the performer, but questions any easy connection between everyday fashion and theatre costume. The presence of the artist’s hand at work on the costume as a co-author of the performance is evidenced in Nicky Gillibrand’s close-up viewing of The Soldierin Chout. The performative qualities of costume detected by Charlotte Hodes in the embroidery of the Meleto Castle costume, articulate the spatial presence, movement and atmosphere that costume can embody. Moreover, the camera in Encounters in the Archive became the facilitator for the research and the encounters as well as providing documentation for further analysis. The resulting film immerses the viewers in the archive, connecting them with the context of costume as an archived object, a context from which it can look outwards to future perspectives.

The research methodologies developed in this project do not aim to replace those currently deployed by ‘design for performance’ scholars, but to balance existing approaches within a context of interdisciplinarity that places the dressed body very much at the centre of the enquiry. As such it contains a multiplicity of expert voices and a multiplicity of performances, which, in the case of poorly debated areas of ‘design for performance’ such as costume, can begin to articulate the complexity of this subject.21

Video: Blythe House - Encounters in the archive

This film was developed and produced by Donatella Barbieri and filmed and edited by Netia Jones. It captures the interaction between the researcher and the object in the archive. It has acted as a catalyst for the creative process of its participants, designers, artists and researchers who have made use of the experience as a way of furthering their own practice through research. For more information about the participants’ own projects and about this film-based research project, please view www.encountersinthearchive.com.

Participants:

Dr Kate Dorney, Curator of Modern & Contemporary Performance at the V&A

Paul Bevan, Photographer and visual artist

Cathy Haill, V&A curator and circus specialist

Amy de la Haye, Curator and fashion historian

Claire Christie, Costumier and senior lecturer

Nicky Gillibrand, Costume designer

Charlotte Hodes, Fine artist

Marios Antoniou, MA fashion student

Darren Cabon, Fashion designer

Transcript:

Kate Dorney: Sixty thousand files of Arts Council material, ten thousand stage plans, twenty thousand stage designs, twenty thousand pieces of costume, three million photographs, two hundred venues where we systematically collect the programs, around five thousand production boxes of material, around two hundred and fifty thousand production files, about two thousand index cards detailing individual performances…

Paul Bevan: Architecturally, what I find quite interesting about this space and the way that it’s laid out. It is sort of organised - I’m sure it’s all terribly organised - and it also looks quite chaotic. But nevertheless there’s a huge physical structure to the way this space is laid out and I think it’s an interesting location in which to engage with knowledge, empirical knowledge.

Kate Dorney: It’s the biggest collection of its kind in the world in terms both of its scope chronologically and in terms of the richness and complexity. We don’t just collect theatre, dance and opera but also musical, circus, rock and pop and pantomime. From beautiful sixteenth century ballet décor and designs for a very rarefied audience to a twenty-first century pantomime.

Cathy Haill: The wonderful thing is that we’ve been given these trunks that Edwin wore; they were such working clothes and weren’t kept in a way that many actors and actresses kept their costumes but if you look at the workmanship in them it’s just beautiful, and this [referring to the embroidery in gold and silver thread] would obviously have shone a lot more. They would have been just worn just with a leotard.

Kate Dorney: We have about three million photographs, twenty thousand stage designs, twenty thousand pieces of costumes going from tiny bits of paste jewellery and ballet shoes up to huge head-dresses and complete outfits. Everything from anonymous designers to Dior and Picasso and Cecil Beaton.

Amy de la Haye: Here we have a dress that Cecil Beaton designed for the stage production My Fair Lady which was shown in London in 1958. He was critically acclaimed for these costumes which he designed as a sort of nostalgic interpretation of dress from just before the First World War. I’ve never seen this before.

Kate Dorney: You’re looking at the accumulation of only a century of collecting which is not very long in museum terms, but because of the subject matter it’s lots of different people bringing their collections together. One man’s collection of 18th century prints meets another man’s collection of 18th century books which meets a solicitor’s collection of carte-de-visite photographs from the 19th century. It’s layer upon layer of material. The last forty years that the department has existed it’s really just the very top layer.

Claire Christie: Evening Standard 1954… Fabulous Lady… this is obviously a ‘special’ on her…

Kate Dorney: Before we were a museum and when lots of people wanted a museum [of theatre], they started out by only collecting [material from] London and only collecting ‘legitimate’ theatre, completely ignoring musical and popular entertainment, the kind of things that people on the ground would understand. We were much more like a fine art style collection. Then gradually, in order to make us into a museum, people started to collect costume like the Ballets Russes Costume for example.

Nicky Gillibrand: That’s amazing… isn’t that just the nicest thing…it’s beautiful… In a way it’s quite amazing that it survived so long, you can’t imagine that the designer thought they [the costumes] would still be alive with us now.

Kate Dorney: The founding collections of the museum are the result of Gabriella Enthoven who was an amateur actress, dramatist and society lady, who decided that there must be a Theatre Museum and she went round successively lobbying every museum and government, she did it for thirteen years, and then the V&A made the mistake of holding an exhibition of international stage design, and she pounced on them and eventually inveigled her way in with a collection of flat material and the V&A very kindly let her stay and let her employ two assistants from her own private income. She got no money, and she paid for everything she acquired, and during that period we acquired lots of really amazing 18th century stage designs, some very early material.

Charlotte Hodes: This is ‘Italian Jupiter’, late 18th century, wonderful. This is a wonderful, hand coloured print of different types of dances. It’s like the whole world on a stage and everything is contained within it and although it suggests that it goes beyond the page, you get the feeling that this world exists here, that there’s nothing else, everything you want to know about the world is all in here.

Kate Dorney: [Regarding visitors to the archive] We have a pretty even split between practitioners and academics so if you include academics as right down to undergraduates. We have also set designers, costume designers, tv researchers.

Marios Antoniou: For my MA proposal I am working to the theme of the clown, performance and circus. I am looking to early costumes in order to draw inspiration, and my aim is to transform costume into contemporary fashion.

Darren Cabon: There’s so much about this that refers to Comme des Garçons. They did a collection in the early 90s which was all wool tailoring, not pressed at all. When the garments were cut and frayed and then put together without any pressing at all, you got this very same effect.

Charlotte Hodes: I’ve never actually seen a costume lying flat. I’ve only ever seen costumes either vertically or on people and in order to animate I have to sense that somebody was in it. My instinct is to project the figure into it and actually to put it vertically and try and imagine how the garment would function on a moving body. Even here, lying here like a carcass you really sense a sort of atmosphere and almost the kind of music and the ambiance that would be there, all that is contained within the garment.

What’s interesting about embroidery from the point of view of a fine artist is that it is essentially not always a kind of linear process. Obviously you can block in areas but you have still got the stitch and the thread so it’s very much like a drawing. It is a drawing really, it’s a drawing with thread and that’s what so thrilling about it. In the equivalent as a painting you can then see the drawn thread and then you see these wonderful rich, dense, sort of velvet reds as painted areas. I can project it as a painting.

[On drawing objects in the museum and in the archive] You undo the distance that you have when you look at an object in a museum. There is a kind of distance and an awe and quite rightly because these objects that we’re looking at are absolutely wonderful and so one is in awe of them but I think that drawing allows you to get over that, so that you can look much more directly at the artefact and connect much more closely. You can almost say this is just you and the object and there’s nothing between you.

Kate Dorney: [On viewing objects] It’s a very rich world. You can see things on the internet and you don’t necessarily have to come and physically see something. But usually what happens is that if someone comes in with a yen to see a particular thing it will be because they have seen it on the internet so there’s a kind of reversed Benjaminian aura, the mechanical reproduction is not good enough you must come and worship at the real thing.

Amy de la Haye: I’m so excited to see this costume because I know it’s pink, and I’ve written about it, but all the photographs are black and white so in my mind’s eye it’s still black and white and beige, so I’ve been really, really looking forward to seeing how pink the pink is. It looks much more artisanal than I’d imagined, I’d imagined it was going to be modernistic and quite a smooth knitted jersey but it actually looks like something hand knitted that someone’s grandmother could have made. And as dance costume actually it’s quite surprising that it has survived when you think how much it would have been worn.

It’s really exciting to see these costumes because they’ve come from possibly one of the most famous Diaghilev productions, Le Train Bleu from 1924, that was shown in London, Paris and Monte Carlo. For me seeing these is extraordinary because I have done a lot of work on Chanel and I’ve looked at her fashion collections and from everything I have read I believed that these costumes would be almost indistinguishable from the sort of sportive designs that she created for her fashion clientele in the 1920s but actually they are completely distinctive.

I have always known it was pink, because all the photographs you see contemporaneously are in sepia tones or in black and white, in your mind’s eye, the costumes are in neutral colours and I think the biggest treat for me is to see quite how rose pink the pink is.

All clothes have got some sort of imprint of wear but the exciting thing about knitwear is perhaps more than any other type of clothing is that it adapts to the shape of the body and so it really is sort of entwined with lives lived and performances performed.

What’s intriguing is the fact that this was a really high profile production but they still mend the costumes, whereas you might think the lead dancer would get new ones but it’s mended all over which also really adds to the human connection of the garment.

Nicky Gillibrand: I can’t believe I’m actually standing in front of them, sorry, it’s quite an emotional moment. The back is just unbelievable; I love the fact the decision not to have a sleeve as a full sleeve of the beige grey wool. The fact that it is a two piece sleeve but they have done it out of two different fabrics, it is really interesting people don’t often think like that.

I love the fact that it stops there [points at panels on the arm] and you’ve got a seam there, and a there and it’s beautiful, it’s really beautiful.

[Looking at flat costume on table] It’s an unbelievable amount of clothing for a dance costume, plus he’s got those giant boots on as well… I just want to see the whole thing on stage now really. This bit here almost looks like it’s something that was a process, I suppose it’s not quite finished, I love the pencil lines.

Kate Dorney: If you’re a researcher you can access flat material in the reading room or the things that on display in the museum. You don’t get to see all the things that are in deep storage or have access to set models or costumes or swords or a pair of acrobats’ trunks, which for some people is very important - just to see the movement, how things changed, how they wear. It’s very difficult to have access to those kinds of things.

Darren Cabon:…and interesting that all of the embroidery was placed on afterwards, after the construction of the garment.

Amy de la Haye: Is it silk lined all the way up?

Susana Hunter: I think the trousers are.

Amy de la Haye: So they wouldn’t be itchy?

Nicky Gillibrand: It’s got this all the way through, has it?

Susana Hunter: Yes, it’s a multilayered skirt.

Charlotte Hodes: Also the fact that it’s raised, it’s tactile it’s coming up, it’s more than decoration its ornamentation it’s absolutely very, very physical.

Claire Christie: So can you see that that’s cut straight like that on the shoulders? It causes it to be a cowl and it’s actually not straight across, its cut slightly curved up… again its slightly high waisted and has got diamond [shaped pattern pieces] in… so this is on the straight coming around from the back, on the hip it’s on the straight. On the front panel of the skirt it’s all bias as well, isn’t that beautiful, how clever is that.

Kate Dorney: Most of the people that come here have been coming since they first found it and keep finding new things. I guess my use of it is about trying to encourage other people to use it.

Endnotes

-

The author’s research for this paper and her placement at the V&A are both intended to question how costume has been easy dismissed, and to re-claim it as a complex and highly charged material object. For this purpose, she is currently writing a book to be jointly published in 2013 by Berg and the V&A, entitled Costume in Performance. ↩︎

-

Netia Jones. Accessed November 23, 2011. https://netiajones.com/ ↩︎

-

Quoted from interview with Janet Birkett on 14 May, 2010. ↩︎

-

Noë, A. Action in Perception. Massachuttes: MIT Press, 2004: 1. ↩︎

-

Monks. A. The Actor in Costume. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010: 9. ↩︎

-

List of reviews accessed on line on January 30, 2012. The Telegraph, June 10, 2011; The Guardian, June 10, 2011; What’s on Stage, June 10, 2011; The Independent. Monday 13 June, 2011; Time Out, Monday June 13, 2011; The Arts Desk, June 10, 2011; The Stage, June 13, 2011; The Observer, June 12, 2011; The London Evening Standard, June 10, 2011; The Financial Times, June 13, 2011. ↩︎

-

Shepherd, S., and M. Wallis. Drama/Theatre/Performance 2004. London: Routledge, 2004:194. ↩︎

-

Wilson, E. Adorned in Dream. London: I B Tauris & Co Ltd; Rev. edition 2003. ↩︎

-

Morrison, R. “At Sizewell I saw the future glowing in the dark”. The Times, June 24, 2011. ↩︎

-

Garner, S. B. Bodied Spaces: Phenomenology and Performance in Contemporary Drama. University of Michighan: Cornell University Press, 1994. ↩︎

-

Quoted from interview with Kate Dorney, April 28, 2010. ↩︎

-

Quoted from interview with Netia Jones, July 6, 2011. ↩︎

-

Noë, A. Action in Perception. Massachuttes: MIT Press, 2004: 1–35. ↩︎

-

Interview with Amy de la Haye, May 13, 2010. ↩︎

-

Garafola, L. Diaghilev Ballet Russes. New York: Da Capo Press, 1987: 108. ↩︎

-

de la Haye, A. Chanel: Couture and Industry. London: V&A Publishing, 2011:48 – 50; de la Haye, A. and S. Tobin. Chanel: The Couturiere at Work. London: Overlook Press, 1997: 46 - 48. ↩︎

-

Quoted from interview with Nicky Gillibrand, May 13, 2010. ↩︎

-

Pritchard, J. and G.Marsh, eds. Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes 1909–1929. London, V&A Publishing: 2010; Theatre Costume for a Solider in Larionov and Slavisky’s ballet Chout, designed by Mikhail Karionov, Diaghilev Ballet, 1921. Victoria and Albert Museum, S.755-1980. ↩︎

-

Theatre Costume form Meleto Castle in Tuscany, mid-18th century. Victoria and Albert Museum, S.92-1978. ↩︎

-

Interview with Charlotte Hodes, on April 28, 2010. ↩︎

-

More information about Encounters in the Archive can be found on the website www.encountersinthearchive.com ↩︎