Abstract

Many exhibits in the V&A’s forthcoming British Design 1948–2012 were collected by the Circulation Department; this article draws on a variety of sources to outline the Department’s activities from 1947 until closure following government cuts in 1977. Was the country deprived of ‘a standard-setting and cost-effective service which continues to fulfil the vision of the original founders of the V&A’, as a petition to the Secretary of State for Education and Science, claimed?1

Introduction

Observant visitors to the V&A exhibition British Design 1948–2012: Innovation for the Modern Age will notice that several of the post-war objects of British design bear a museum number with the prefix ‘Circ’ (fig. 1). This prefix is not a reference to some uncertainty about the object’s date (‘circa’) but an abbreviation of a now defunct department of the Museum – the Circulation Department – in-house known simply as ‘Circ’. Circ operated from what is now the temporary exhibition space, beyond Room 38A. The Department was responsible for loan shows that travelled to two categories of venue – to regional museums, art galleries and public libraries, and to art schools and education colleges; thus disseminating art and design across the UK. Today the vehement reaction to Circ’s closure in 1977 is not the only evidence of the Department’s achievements.

The ‘Circ’ objects selected for the forthcoming exhibition can be considered as having a reciprocal relationship with British design, since they travelled so widely across the UK. The ‘Art and Design for All’ dictum celebrated by the recent Bonn Exhibition and the current government agenda on regional engagement show the enduring value of the democratic ethos of the Department under Keeper Peter Floud CBE (1947–60) and later Hugh Wakefield (1960–76).2 It is a tribute to the energy of Circ staff and their significance in the history of contemporary collecting by the V&A that ‘Circ’ objects span such a variety of styles, mediums and functions, from a Lucie Rie bowl to Kenneth Grange’s Chefette.3 The history of the Victoria and Albert Museum has been well researched but a detailed history of the Circulation Department remains to be written and this article builds on new and extensive primary research in the V&A’s own archive files at Blythe House.4 The Department’s formal activities were published yearly in booklet and prospectus form and others have interviewed Circulation staff as part of the ongoing V&A Oral History project.5 This article uses a range of research mediums to outline the post-war ethos of the Circulation Department and the variety of shows travelling to museums. Loans to art schools and colleges and the evolution of this service are discussed in some detail, as is the acquisitions policy. The article closes with reactions to the decision to axe the Department following government cuts in 1977.

Ethos

Until closure in 1977, the Circulation Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum could be considered the oldest such institution for the preparation of travelling exhibitions of museum material in the world, originating as part of the Design Reform initiative centred on the Government Schools of Design at Marlborough House.6 Following a major re-organisation of the Museum in 1909, each V&A Department transferred part of its collection to Circulation for loan to the regions. By 1950 the Department’s own distinct holdings amounted to over 25,000 objects and today the current official total of ‘Circ’ objects is over 32,000.7 The Circulation collection did ‘not in any way represent a collection of “throw-outs”, discarded as being unworthy of exhibition at South Kensington, or even of second-class examples of lesser monetary value’, as the Keeper Peter Floud emphasized in 1950.8 The Circulation collections consisted of a selection of the whole Museum’s collections, and included important objects such as a seventeenth-century Thomas Toft plate and Thomas Girtin’s ‘Warkworth Hermitage’. Circulation staff were more concerned with acquiring contemporary work than the other Departments of the ‘parent’ museum, aiming to collect the best British and international work in the field of the decorative and graphic arts. As the future Keeper, Hugh Wakefield, noted in 1959, Circ acted, ‘as the growth-point of the Museum’, ranking ‘as the national collections of the present and of the past hundred years’.9

This focus on comparatively recent and even contemporary objects gave Circ a distinct identity in relation to the Museum as a whole, close to its original mission, arguably more ‘redolent of modernity’ and liberal in instinct.10 Within the Museum, Circ staff were seen as left-wing in sympathy and less scholarly in their approach to objects, perhaps due to the specific demands of travelling shows. Under Floud, however, Circ established a reputation for innovative scholarship in fields then ignored by other departments of the Museum, such as Victorian and Edwardian design.11 The Oxbridge background of senior Circ staff of the post-war period can be seen as traditionally ‘Establishment’ but this did not prevent them from promoting a number of assistants with art school training.12 The underlying principle of the Department’s circulating exhibitions was that they should be shown in institutions open to the public without charge. Exhibition design supported this aim through full labels and descriptive notes, often mounted on a lectern, obviating the need to purchase explanatory catalogues. Whilst catalogues were available for a limited number of shows (just six out of sixty-one in 1959, for example) these were modestly priced, and provincial institutions were supported in producing their own catalogues as the Department provided detailed text. Equality of access was further promoted by the charging structure: where a standard transport fee applied irrespective of the borrower’s location in the UK, and through the Department’s willingness to consider loans to a variety of institutions, provided these were secure.13

British design and the Circulation Department

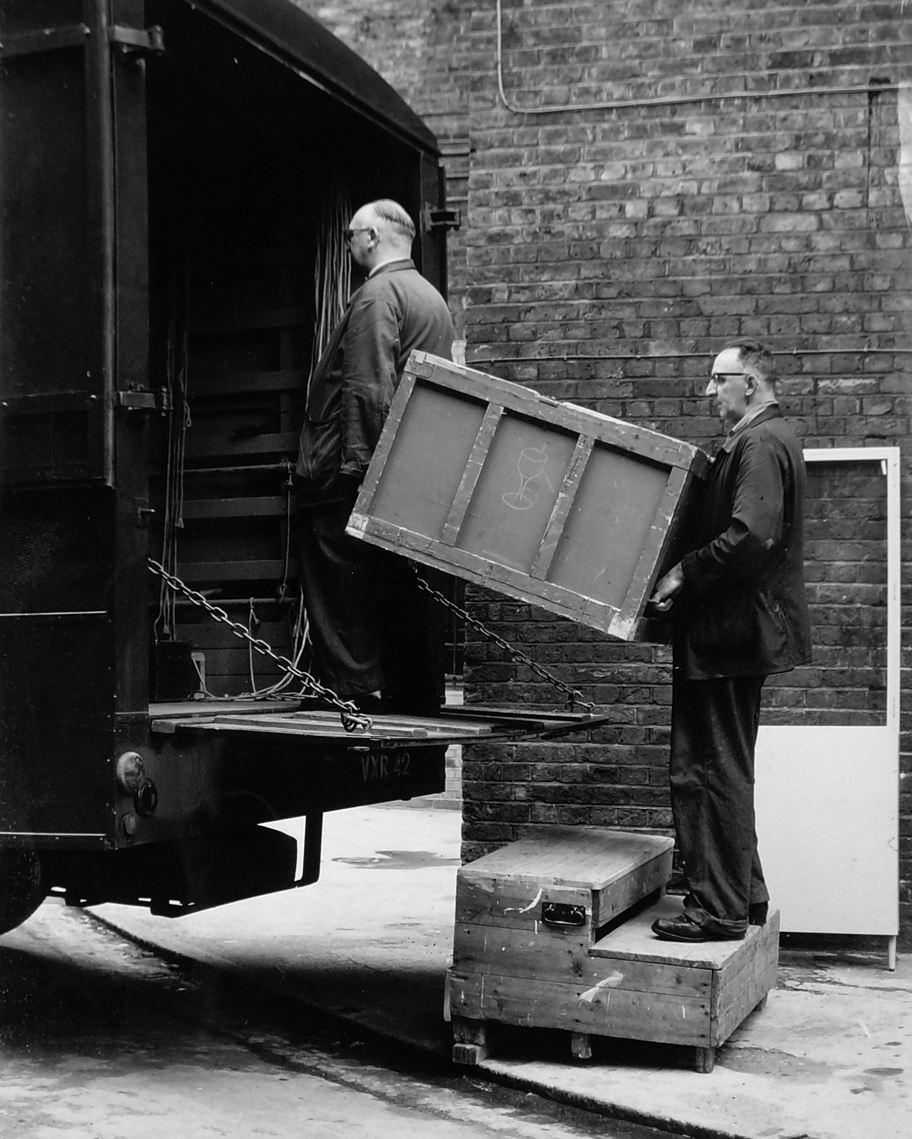

The Circulation Department may be seen as having a reciprocal relationship with design in post-war Britain through its shows in museums, galleries and art schools across the UK. The Department’s travelling exhibitions were in the ‘long tradition of placing, at the disposal of regional museums and galleries, its expertise in every field of activity within the sphere of the fine and decorative arts’ (fig. 2).14

Regional museums and art galleries

Peter Floud joined the Circulation Department in 1935, leaving in 1939 when the Department closed during the war, and returning as Keeper of Circulation to re-open the Department early in 1947. In Floud’s view, ‘all museums can be of use to intelligent teachers’ and museums are, ‘anxious to be of use’, echoing Henry Cole’s dictum of a ‘schoolroom for everyone’.15 Floud made changes to museum circulation, introducing shorter loans and a range of exhibitions that responded to the very different sizes and needs of the host museums, galleries and other institutions. Travelling exhibitions were ‘specially prepared for the typical small general museum which needs non-specialist exhibitions, appealing to a completely uninformed public’. Such exhibitions were ‘supplied with much fuller and more didactic labels than would normally accompany a Victoria and Albert exhibition’.16

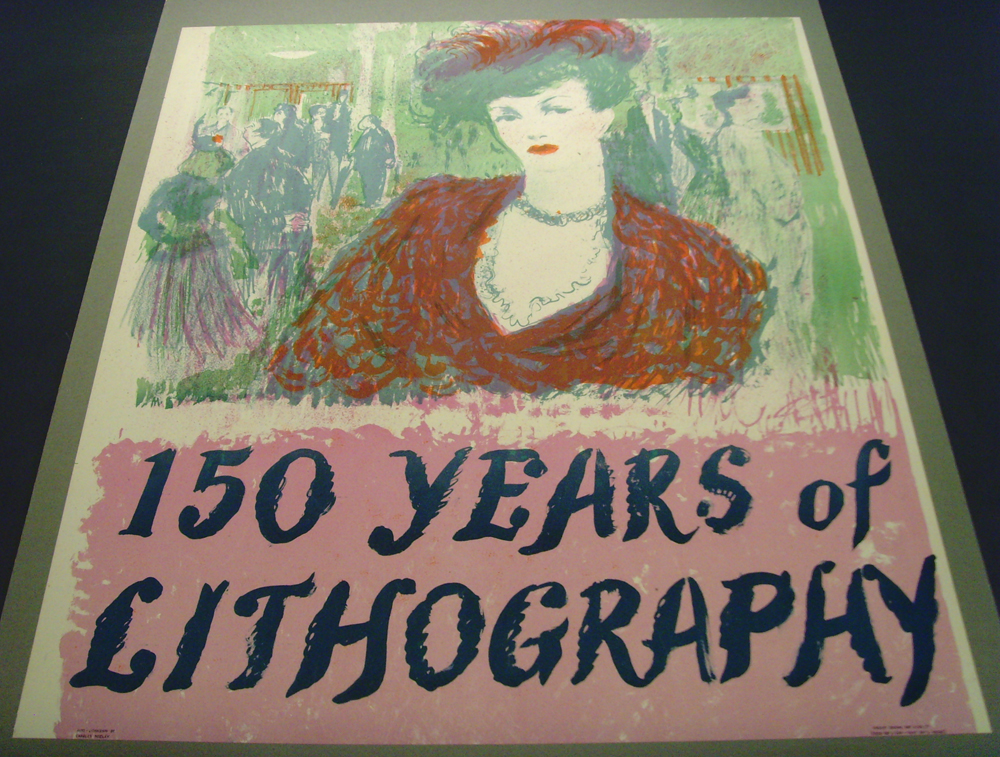

Arguably such explicit aims could be seen as patronising to provincial galleries but, given an understanding of the democratic aims of the department, this approach may be seen as pragmatic in promoting access for all. Starting in 1947, Floud quickly constructed some 15 larger travelling exhibitions that toured in standard travelling showcases and offered provincial galleries a complete survey show, for example on Gothic or Islamic Art. What is notable about these exhibitions is the variety of original material employed to represent the subject in a manner that cut across the Museum’s own Departmental division into materials. The Islamic Art show contained glass, ceramics, woodwork, ivory, metalwork, brocades, velvets, miniatures and book-bindings, in a manner we might associate with a more modern approach to ‘material culture’. Survey exhibitions were comprehensive and of high quality, for example the History of Lithography contained 150 prints ranging from Goya to Picasso (fig. 3).17

In considering the diverse needs of regional host venues, Floud and his team produced both shows that were limited to two-dimensional material for hanging and those containing only three-dimensional material for galleries with limited wall space. There was a post-war trend for the more important Circulation Department exhibitions to be shown at South Kensington ‘before being sent to the provinces’.18 There was also a deliberate policy to use designers from outside the Museum for a proportion of Circulation Department exhibitions, giving them a distinct identity.19 Floud stressed the importance of established channels of distribution without which circulating exhibitions would, as he writes with some feeling, ‘moulder in the storage vaults of the bureaucratic organisations’.20

By the mid 1960s under Keeper Hugh Wakefield, travelling exhibitions for museums and art galleries covered a variety of periods and media, sometimes being formed in co-operation with other museums (for example, European Arms and Armour with loans from the Burrell Collection, Glasgow, and the Tower Armouries), in response to new bequests (for example Chinese Export Porcelain from Basil Ionides) or to appeal to a particular type of museum visitor (for example Animals in Art - with the superbly appropriate order code ‘ED1’ - to educate children).21 Travelling exhibitions often amounted to collaborative ventures that utilised the expertise and collection loans of a variety of regional museums and varied from those with popular appeal such as Oriental Puppets to more ‘serious’ exhibitions with an explicit appeal for knowledgeable collectors like London Porcelain.22

Though the Circulation Department had a reputation for maintaining an independent stance within the Museum, it nevertheless did work with colleagues in other departments to produce exhibitions.24 The Department also produced exhibitions using objects from other V&A departments, for example Peasant Rugs and Wall-hangings with the Textiles Department.25 Circulation Department exhibitions could contribute to the rise in status of objects regarded elsewhere in the Museum as ‘mere ephemera’, for example Posters of the Fin-de-Siecle, a Schools Loan in 1964–65.26

Travelling exhibitions were shown right across the regions, for example in 1964–65 British Studio Pottery travelled to Belfast, Glasgow, Keighley, Kettering and Lancaster. Venues happily accepted a wide variety of exhibitions spanning different periods and media, for example in 1964–65 Belfast Arts Council Gallery hosted exhibitions as diverse as British Studio Pottery; Contemporary Italian Prints; Twentieth-century French Prints; and European Arms and Armour.27 Loan exhibitions might contain contemporary British work such as Weaving for Walls organised with the Association of Guilds of Weavers, Spinners and Dyers, or historic material in thematic displays such as The Italian Renaissance. This Italian Renaissance exhibition contained a mouth-watering diversity of objects - Maiolica from Faenza, Deruta and Urbino, Della Robbia ware, Venetian glass, terracottas, bronzes, metalwork, marquetry, gesso-work, leatherwork, textiles, framed original prints, illuminated manuscripts, bookbindings, embroidery, lace, and architectural photographs.

Exhibitions could be designed in a didactic manner to show evolution in design, for example through the 25 chairs dating from the seventeenth century to the mid-sixties displayed in The English Chair.28 Exhibitions illustrating development could end with especially commissioned works making the Circulation Department’s role as arbiters of contemporary design taste explicit, as in Tiles which contained tiles from the Middle East and Europe, from 1200 up to the work of Finnish artist Rut Bryk in 1963.29 (fig. 4) Post-war the Department used its independent acquisitions funds to encourage particular design approaches by commissioning pieces for the permanent collections.30

Circ exhibitions could lead to a revival in a particular industry, as is claimed for the 1955 English Chintz: Two Centuries of Changing Taste show held with Manchester’s Cotton Board, or for a particular designer, as with the Victorian and Edwardian Decorative Arts show and William Morris.31 At South Kensington from the mid-sixties, the Department showed a frequently changing series of small exhibitions, and recent modern acquisitions in the northern and southern halves of the Restaurant Gallery respectively, making these available to ‘the considerable public which uses the restaurant’.32 These shows, geographically close to the Department’s offices ‘beyond Room 38A’, have received little scholarly attention but students from the Royal College of Art who studied within the South Kensington buildings were influenced by these Circ exhibitions.33

Regional art schools

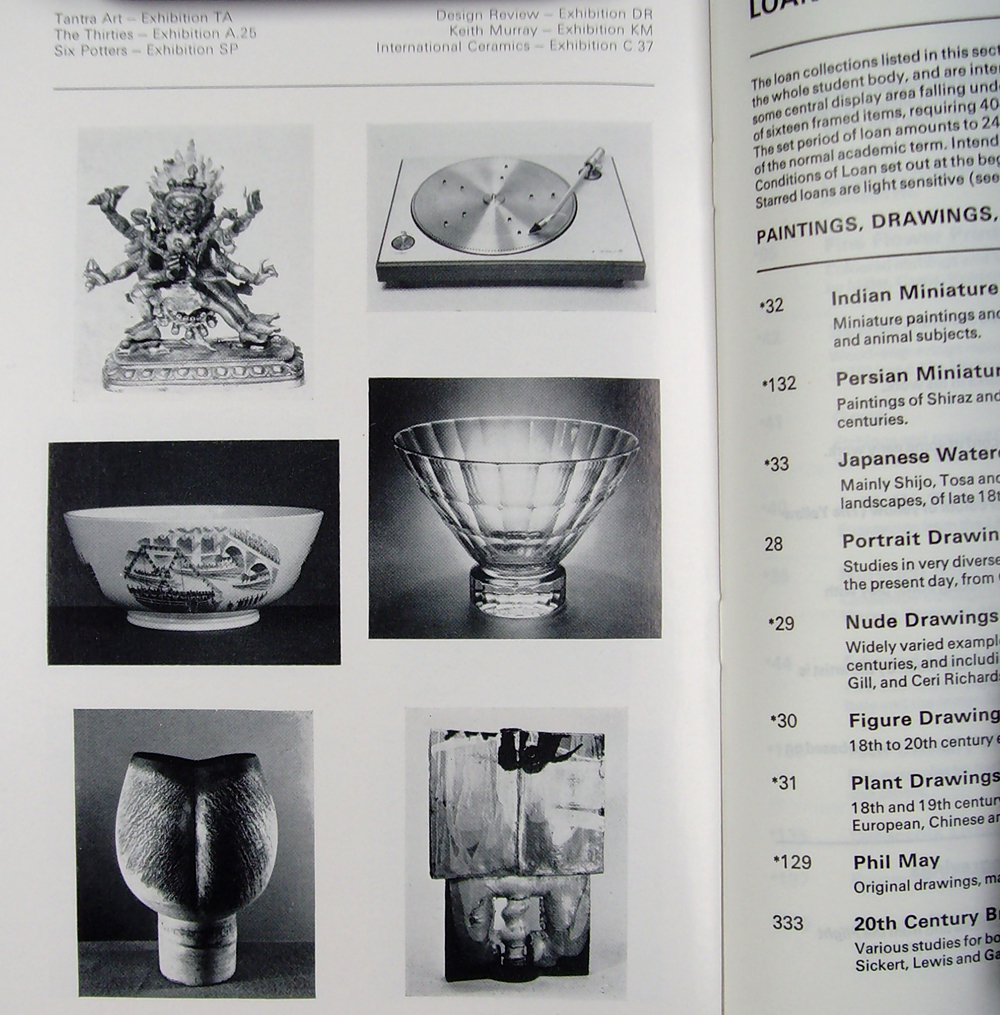

Loans to art schools and teachers’ training colleges were re-established after the war, starting in 1948, although as the Museum’s own archive is incomplete, the first post-war Circulation prospectus dates from the academic year 1951–52.34 By this date the Department was circulating collections to some 270 educational institutions around the UK and aimed to provide a service tailored to their specific needs; for example, sending out a questionnaire in 1950.36 The 1951–52 prospectus made available 125 different categories of ‘sets’ usually of 18 frames of original material, photographs, facsimile and collotype reproductions. The proposed audience may be seen to relate to the divisions of teaching departments in art schools and also to the departments of the Museum.37

The order and division of the categories of schools sets changed over the post-war period but overall the hierarchy continued to emphasise two-dimensional fine art material.38 Some framed sets had a structured didactic purpose such as The Decorative Arts in England designed as a series of six running in chronological order from 1675 to 1825 to be shown for a term at a time in sequence, thus educating students over six terms, or two academic years. Sets of facsimile reproductions were of traditional old masters, as for Holbein Drawings; on a theme as for Figure Studies, covering national schools such as Flemish Drawings; or selected to illustrate contrasting styles; like Classical and Romantic.

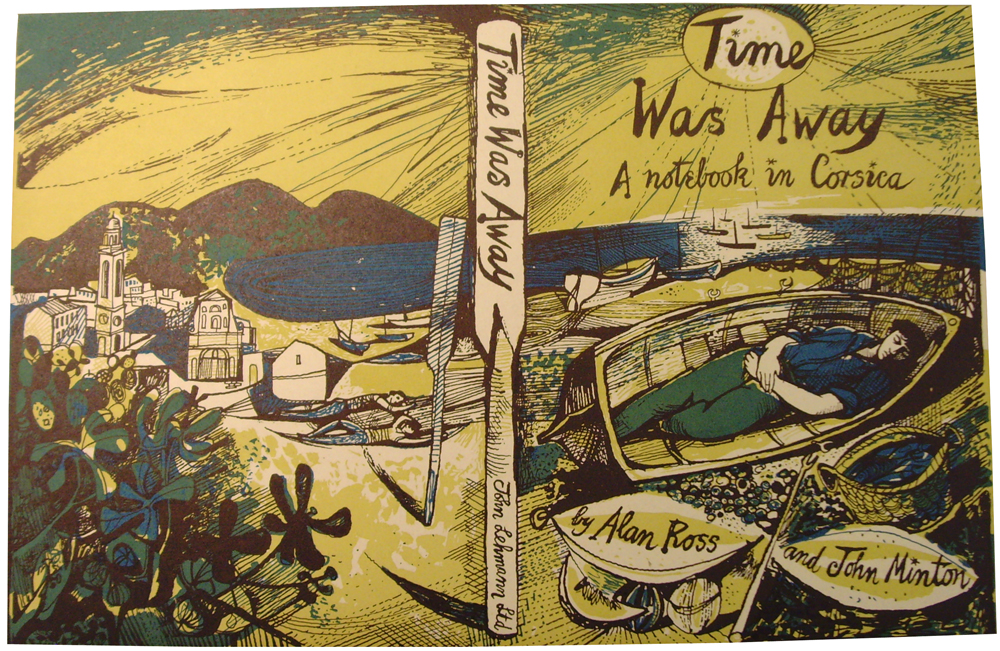

Art school sets were also created for particular departments to teach technical processes and their historical development, such as The History of Wood-engraving and Wood-Cutting and The Process of Wood-engraving and Wood-cutting, brought up to date by Contemporary Wood-engravings and Wood-cuts. Some sets are of interest today as they were the result of the Department’s collaboration with well-known practitioners. John Minton is represented in the Colour Line-Block set of artist-separated line-block illustrations in progressive colour-proofs (fig. 5).39 Marianne Straub created a didactic set of ‘tabby-weaving’ with examples by Peter Collingwood added later. The set was commissioned ‘to illustrate the variety of textures and effects obtainable in a single simple weave’ from ‘a leading individual weaver’.40 In one innovation some loans to art schools could be handled as contemporary textiles were supplied hanging loose.41

Art school sets were international in scope, for example, ‘Contemporary Illustrated Children’s Books included English, French, Swiss, Danish, Polish, Czech, and Russian books. In the immediate post-war period, the Department offered regional art schools unusual and hard to obtain original contemporary material such as foreign posters, ‘rarely seen by the general public’ in Contemporary Posters and ‘export only’ fabrics, ‘not seen on the home market’ in Contemporary Miscellaneous Textiles. There were inherent difficulties in framing certain art objects, so that ceramic tiles are present as originals, whilst sculpture was necessarily photographed. Even at the early date of 1951, commercial design was not neglected, for example ‘Commercial Packaging’ showed a varied selection of mainly foreign contemporary package design.42

Development of service to regional art schools

By the mid-1950s the Department circulated its collections to around 300 schools of art right across the UK with about 170 different subjects covered in 510 framed sets. The pool of framed sets available totalled 11,250 with that of unframed material being 20,000, including the duplicate sets of popular material. A staggering 1,200 framed exhibits were staged with an additional 6,000 showings of unframed mounts in 1955/56. In addition, the Museums section of the Department had shown some 61 different exhibitions to 136 galleries, a total of 300 showings.43 This prospectus also listed the most popular sets so that schools of art could order strategically and stand a better chance of receiving sets they wanted. The most popular sets were of textiles; Teaching of Embroidery and Wax Resist-Dyed and Printed Cottons. Other sets which also received more than 20 requests included great artists of the western canon like Da Vinci, as well as modern graphic material such as Contemporary Greeting Cards. A similarly varied mix, perhaps surprisingly, received more than 10 requests, for example Raphael and Commercial Packaging.44 In 1963, moving with the times, the Typography and Printing category offered Contemporary Book-Jackets, Record Sleeves, mainly of foreign origin although some were British.45

The variety in media, period and location seen in loans to museums continued in Schools Loans, for example in 1964–65 Posters of the Fin-de-Siecle travelled to Coventry College of Education, Leeds University Department of Fine Art, Leicester College of Art, Newcastle on Tyne College of Art and Industrial Design and Oxford School of Art.46 In the late 1960s copies and reproductions of works of art were withdrawn from Schools Loan circulation as these were seen as a poor substitute for ‘first-hand contact with original and unique works of art’; perhaps by this date good quality illustrations in books, magazines and slides were more widely available.47 Art school loans began to be constructed less as ‘illustrated histories’ with technical relevance for a specific craft or medium and rather aimed to be of general interest to art and design students by ‘enlarging their daily horizon’. The display locations of these loans changed and they were shown in central areas rather than in individual studios, with the aim that a fabric might inspire painters and graphic design inspire fashion students, reflecting a more general period trend towards interdisciplinarity.48

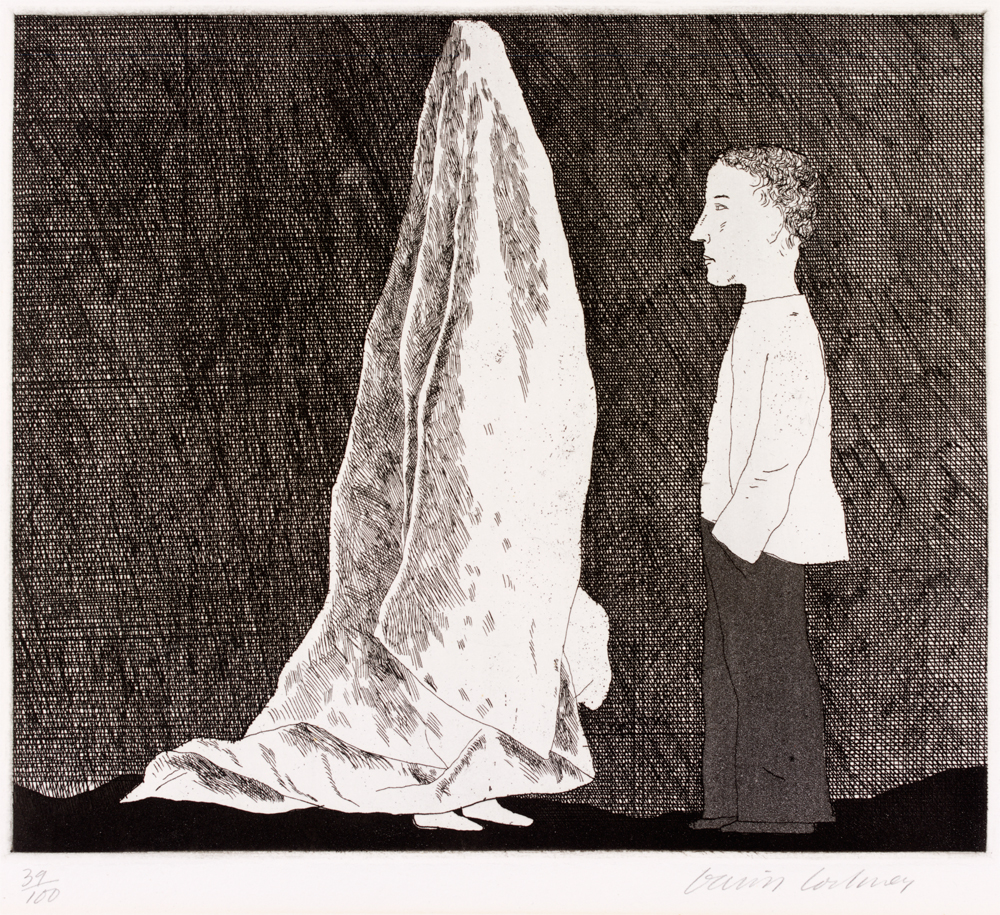

In 1968 the speed of loan turnover increased with the basic period being three or four weeks to occupy just half an academic term, although art schools could double this to cover a whole term as before. The Drawings category showed traditional and modern art that linked the work of contemporary artists to that of known masters, for example Twentieth-Century British Drawings contained work by Sickert and by Peter Blake. Circ simultaneously toured high quality original fine art etchings by Canaletto, Piranesi and Tiepolo lent by the Trustees of the British Museum with its own recently acquired contemporary material, ensuring the regions enjoyed the latest developments in art.49 In 1971, for example, Circ acquired David Hockney’s etchings Six Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm of 1969–70, published in 1971; this material went out on loan in the academic year 1972–73 and visited a variety of locations and venues around the UK, from city museums and libraries to universities and smaller country galleries.50 (fig. 6) By 1972–73, the service held 180 loan collections which were shown a total of 729 times in art schools and colleges around the UK.51

Acquisitions policy

Unlike other Museum departments which had a ‘fifty year rule’ against purchasing recent objects, Circ continued the founding mission to collect contemporary design as an educational resource for manufacturers, designers and the public. At the start of the post-war period Peter Floud could already write that ‘the Circulation Department’s contemporary collections are now much more extensive than those of the main Museum’.52 Peter Floud’s first acquisitions for the Department were a selection of French lithographs purchased direct from Paris.53 Contemporary textiles became a strength of the Department and early acquisitions were a mixture of gift and purchase sometimes even from the same manufacturer at the same time.54 This emphasis on two-dimensional material reflects the ease with which such material could be transported to disseminate contemporary international design to a wide audience, largely starved of such stimulus during the war years.55 Circ was prepared to consider material for exhibition that would have been rejected by other Museum departments, a policy supported by the then Director, Leigh Ashton.57 The Department’s collecting policy was in advance of the market, enabling them to acquire objects at good prices.58 Collecting the work of living designers was, however, considered problematic at the start of the 1950s; though even this did not prevent the Department from acquiring such material.59 In addition to concerns about showing preference to particular designers and firms, either causing offence or giving commercial advantage, there was the possibility of arbitrary personal curatorial taste, the ideal being to eliminate anachronisms and build a classic and enduring collection.60 As other commentators have noted, Circ’s acquisitions of modern material were not universally bold in taste.61

The Circulation Department’s policy to purchase contemporary design responded to, ‘an overwhelming bias of demand’ for loan exhibitions of modern work from large colleges of art.62 The principals of art colleges required exhibitions of new and contemporary material to make an impact as works needed an appeal that was, ‘strictly of the moment’, necessitating a ‘ruthless turnover of material’.63 Contemporary work donated to the Museum by artists was sent straight out in travelling exhibitions to disseminate contemporary design to students and the public. Following Eduardo Paolozzi’s 1971 gift of the collages shown at his 1952 lecture to the Independent Group at the ICA, the artist gave an edition of his ‘Bunk’ prints to the Museum on publication in 1972, forming an exhibition that travelled to public galleries in Dundee, Luton and Wolverhampton in 1973–4.64 The speed with which such artwork was listed in the prospectus and sent out to art schools is impressive. The Circulation Department was able to purchase contemporary material that would have been controversial in other Departments without going through the full formal procedure for approval, in part due to the low monetary value of such objects which could, therefore, be purchased out of petty cash.65 Work acquired directly from Circ visits to art schools and at student shows was usually free, gifted by students pleased to be selected for the Museum collection.66

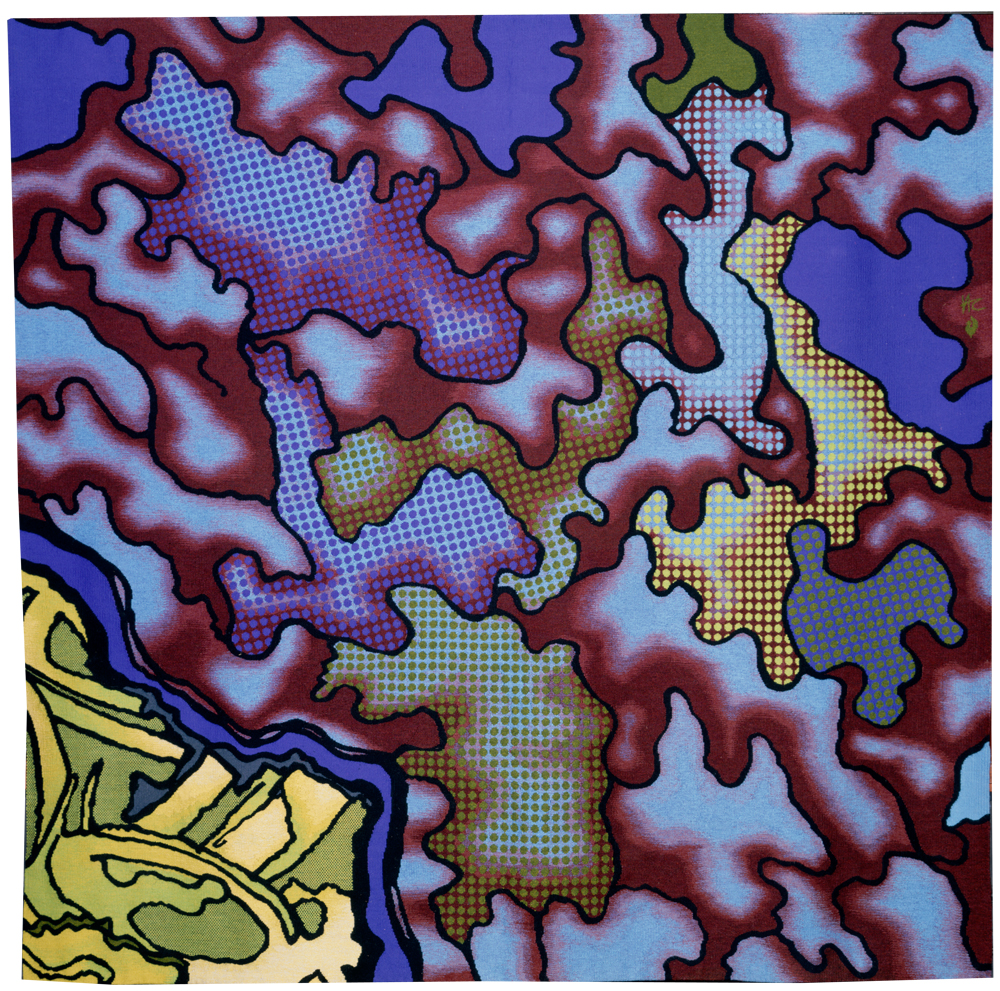

Contemporary material could still be problematic, particularly when the Department commissioned artists and makers to produce objects for touring collections. Circulation, like other Museum departments, sought to maintain complete freedom of taste and choice in its acquisitions. Circ rejected any suggestion that it ‘should need to refer elsewhere for proper discrimination’ in the field of modern design or should compromise, ‘taste and direction’ when commissioning high quality designs in a contemporary idiom that would appeal to teachers and students (fig. 7).67 A number of the ‘of the moment’ exhibitions of contemporary design of a ‘more experimental nature’ that were originally formed as special exhibitions for the Schools Loan Service (under the direction of Carol Hogben, Deputy Keeper of Circulation) were also shown later at regional museums through the Travelling Exhibitions service, for example Pop Graphics.68 These transfers to Travelling Exhibitions could include contemporary material whose ‘value’ was explicitly affirmed by its acquisition by the Circulation Department, displayed together with works still in the collections of art dealers and potentially available to purchase.69 Circulation Department exhibitions also promoted emerging British design talent across the UK by exhibiting the work of students from regional centres of excellence, with the open aim of encouraging particular industries.70

Whilst the Circ emphasis tended to be on two-dimensional or easily transported material, larger industrial designs were accessioned after the decision to accept those objects given Design Centre Awards. Selections of the Design Centre Award objects were circulated as part of the art schools programme, often with design drawings and blueprints so that students could see the process of design undertaken by successful designers such as Kenneth Grange.71 Following this development, Carol Hogben proposed to circulate examples of industrial design from abroad to provide UK art schools with an international overview of design developments and a balance to British designs. Criticism of this approach, which could be seen as a government-funded department giving commercial advantage to foreign competitors, was countered by touring only those objects which had also won a design award in their own country, for example the Beogram 1202 turntable by Jacob Jensen for Bang &Olufsen which won an award from the Danish Society of Industrial Design in 1969 (fig. 8).72 By 1971, The Sunday Telegraph could write that it was ‘good to know that British, and indeed international, craftsmen and designers now have a pretty generous ‘patron’. For around 1,000 ‘contemporary objects’, anything from an award-winning telephone to a Pop festival poster, are bought and collected by the Circulation Department each year.’73

Closure: a standard setting and cost-effective service

In the early 1970s the staff numbered some 38, in two near equal sections, with 70 travelling exhibitions for museums and galleries, and 20 shows and 230 collections for art schools.74 The Circulation Department was well known for its ability to tour exhibitions of popular contemporary material to a huge range of venues across the country and was viewed as ‘an alternative museum, a museum broken up into small, coherent units, and constantly on the road’ and described as ‘one of the real splendours of the V & A’.75 The Department’s focus on contemporary acquisitions was seen as showing ‘great imagination and foresight, forming a museum within a museum’.77 This distinct role was blurred from 1975 when the V&A Director, Sir Roy Strong, allocated special funds for the acquisition of post-1920 objects by other curatorial Departments, marking a change in official attitudes towards the Museum’s founding educational mission.

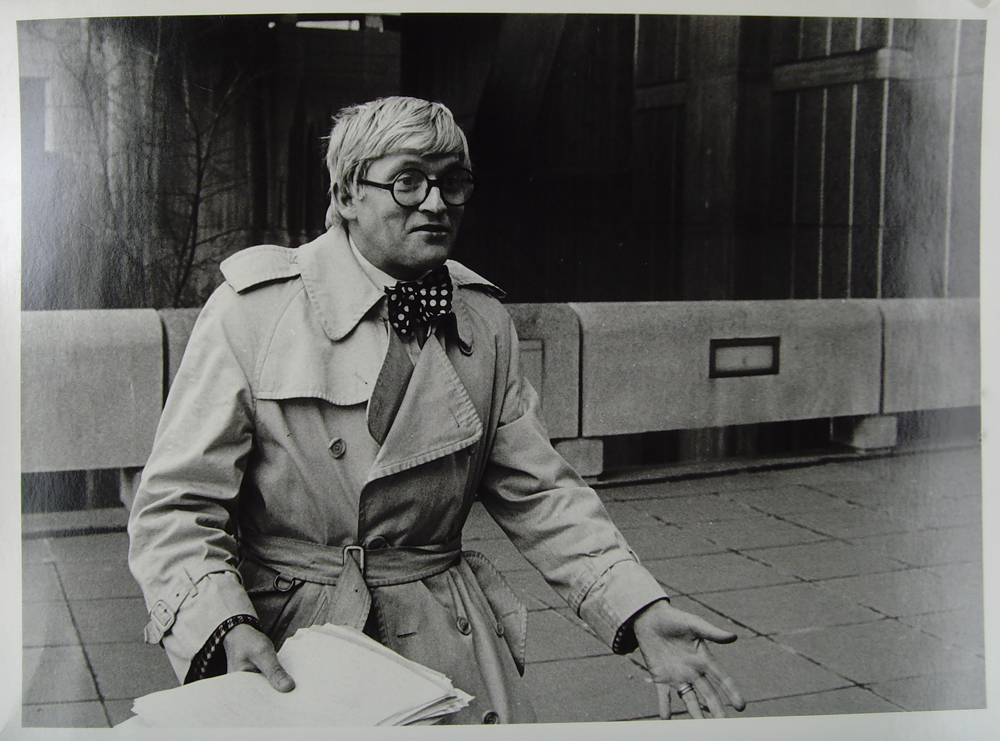

The Department was first amalgamated with the Education Department to become the Department of Regional Services but news of its complete disbandment in late 1976, due to government cuts, was greeted with dismay. In December 1976 following Strong’s announcement of Circ’s fate, David Hockney presented a petition signed by artists, art critics, college principals and historians to Labour’s Shirley Williams, Secretary of State for Education and Science, protesting against the Department’s closure (fig. 9). These prominent petitioners pointed out that the closure ‘would irretrievably deprive the nation of ready access to a significant part of its art collections’ and ‘deprive the whole country of a standard-setting and cost-effective service which continues to fulfil the vision of the original founders of the V&A’.78 The secretary of the Museums Association was quoted saying that, ‘the V&A material which is sent out is a highly valuable means of bringing modern design and contemporary craftsmanship to the notice of the public in the provinces’.79

Users of the Schools Loans service bemoaned the fact that without the Circulation Department, ‘the Victoria and Albert Museum would become just another passive, metropolitan monolith, to be visited by out-of-towners once or twice a year’.80 Regional venues for travelling exhibitions felt that the closure would ‘cut off the provinces from a source of educational and artistic material which we have now come to count on very greatly indeed’.81 A militant Merseyside County Council was ‘prepared to lead a provincial revolt against the London art establishment’ by withdrawing co-operation unless the closure was dropped.82 Some commentators, whilst recognising that underfunding of regional museums had led to a dependence on the V&A travelling exhibitions, were less sympathetic. ‘Merseyside may huff and puff about being deprived of their exhibitions from London, but what cultural facilities are they generating through their own resources?’83 Strong perhaps hoped that Labour’s support for the regions would result in the over-ruling of his proposal to impose government cuts solely on Circ and counted on a vociferous backlash from regional voters galvanising MPs around the country but, despite debate in both Houses, the Department was disbanded. Circulation staff either left or were moved to posts elsewhere in the Museum, with the collection being absorbed, very gradually, into other Departments, creating a heavy workload for them. The remaining Keepers then took up the role of‘strengthening the Museum’s representation of twentieth-century design’ and to emphasise this commitment the Museum created a temporary exhibition, Objects – The V&A Collects 1974–78, the period that spanned the closure of Circ, to give a ‘preview’ of the projected Twentieth Century Gallery.84

To the V&A’s credit, current DCMS performance indicators of regional engagement – the terminology may have changed since Henry Cole’s day but the intent remains – show the Museum as considerably in advance of comparable London museums with loans to 254 venues around the UK in 2009–10.86 Collecting contemporary design has returned to a central position in the Museum’s work, whilst long-term relationships with the regions continue to be developed at Sheffield and Dundee. The Circulation Department and its many activities beyond Room 38A officially ceased in April 1977. The last recorded purchase by the Circulation Department was a Misha Black 1938 wireless design for Ekco for £40 87 whilst the final accession was a Design Centre Award winner, an automatic helm system for tiller-steered yachts by Derek Fawcett.88 The very last recipient of a Circulation Department exhibition should have been the Bowes Museum at Barnard Castle which would have returned ‘Minton’ to South Kensington on 12 November 1977, however, due to closure, the Minton show never travelled. A Victorian initiative to drive forward good British design had ended.89

Acknowledgements

This research has been undertaken as part of the AHRC funded CDA, ‘Disseminating Design: museums and the circulation of design collections 1945 – present day’, a collaboration between the Research Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Centre for Research and Development, University of Brighton, 2010–15. I am grateful for the support of Professor Jonathan Woodham, University of Brighton, Professor Christopher Breward, University of Edinburgh, and Ghislaine Wood, Research Department, Victoria and Albert Museum. My thanks go to the V&A Online Journal’s reader, to Lily Crowther, Angela McShane, Matthew Partington, Ella Ravilious, Linda Sandino, Eric Turner and Helen Woodfield at South Kensington, the staff of the National Art Library and V&A Archive, particularly James Sutton, the staff of the Library and Design Archive at the University of Brighton, and to Elizabeth Bailey and Catherine Kinley.

Endnotes

Abbreviations: V&A Archive – VAA; National Art Library – NAL.

-

Our Arts Reporter. ‘Artists oppose V&A cut’. The Times, 16 December, 1976: 8. ↩︎

-

Von Plessen, Marie-Louise.; Julius Bryant (co-curators). Art and Design for All. Kunst-und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik, Bonn, 2011–2012. ↩︎

-

Bottle, Lucie Rie, 1959. Museum no. CIRC.126–1959 and Electric food processor. Museum no. CIRC.731-1968 both proposed for Breward, Christopher. British Design 1948–2012. Victoria and Albert Museum, 2012. ↩︎

-

The standard works on the Victoria and Albert Museum are as follows. Burton, Anthony. Vision and accident: the story of the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: 1999. Baker, Malcolm and Brenda Richardson. A Grand design: the art of the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: 1997. Somers Cocks, Anna. The Victoria and Albert Museum, the making of the collection. Leicester: 1980. The Circulation Department is also covered in Morris, Barbara. Inspiration for design: The influence of the Victoria & Albert Museum. London: 1986. See also Floud, Peter. V&A Museum Circulation Department, Its History and Scope. London: V&A, Curwen Press: post-1949. ↩︎

-

For example, NAL PP.11.H. CW. The Year’s Work 1964–65, 1965–66, 1966–67, 1973–74. As part of the V&A Oral History project Matthew Partington, Linda Sandino and Anthony Burton have interviewed Circulation Department staff (Barkley, Coachworth, Elzea, Hogben, Knowles, Morris, Opie), although some of these have yet to be formally released. The official version of the Circulation Department closure is given in Burton, Anthony, ed. Review of the Years 1974–78.London: V&A, 1981. ↩︎

-

As the V&A Online Journal’s Reader rightly points out, the early art schools were circulating contemporary objects from Paris from 1844; see Wainwright, Clive and Charlotte Gere. ‘The Making of the South Kensington Museum I: The Government Schools of Design and founding collection 1837–51’. Journal of the History of Collections 14:1 (2002). In 1948 Peter Floud dated the start of Circ to 1848 and the Italian purchases of Mr Gruner for the Schools of Design; see MA/15/14, draft radio broadcast on Circ’s centenary. See also Floud, Peter. ‘The Circulation Department of the Victoria & Albert Museum’. Museum3.4 (1950): 299 ‘Museums and circulating exhibitions’, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, Paris, UNESCO publication 852. A summary of Design Reform is: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Oshinsky, Sara J. ‘Design Reform’. Accessed October, 2011. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dsrf/hd_dsrf.htm ↩︎

-

CIRC prefixed objects totalled 32,493 at 17.8.11: V&A CMS. ↩︎

-

Floud, Peter. ‘The Circulation Department of the Victoria & Albert Museum’. Museum 3.4 (1950): 299 ‘Museums and circulating exhibitions’, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, Paris, UNESCO publication 852. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/15/23. Wakefield, Hugh, ‘The Circulation Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum’. In Hugh Wakefield and Gabriel White. Handbook for Museum Curators, Part F, Temporary Activities, Section 1, Circulating Exhibitions. London: The Museums Association, 1959: 7–17. In addition to contemporary material, Circ was also responsible for the acquisition of many of the Museum’s Victorian objects through: Victorian and Edwardian Decorative Arts. Victoria and Albert Museum, 1952. For example, Catalogue No. 8. ‘Loan by Mrs A.M.H. Westland of Decanter, silver mounted glass bottle set with precious stones and antique coins, by William Burges 1866’, now CIRC.857-1956. ↩︎

-

The Museum has been described as created ‘from a pot-pourri of influences redolent of modernity – international exhibitions, the department store, liberal economics, technical design education and utilitarian reform ideology yet it was also informed also by the more traditional curatorial and aesthetic motivations of John Charles Robinson and his successors.’ Barringer notes that ‘South Kensington was large, impersonal, bureaucratic, systematic and liberal in its economic and political instincts’. See Barringer, Tim. ‘Victorian Culture and the Museum: Before and After the White Cube’. Journal of Victorian Culture 11.1 (2006):133–145. ↩︎

-

Linda Sandino’s interview with Barbara Morris gives useful context. Sandino, Linda. ‘News from the Past: Oral History at the V&A’. V&A Online Journal 2 (2009). Accessed December 12, 2010. [https://www.vam.ac.uk/res/cons/research/online/journal/journal-2-index/sandino-oral-history/index.html] On the research undertaken for ‘English Chintz’ 1960, for example see: Morris, Barbara. Inspiration for Design, The influence of the Victoria and Albert Museum. London, 1986: 116. ↩︎

-

Peter Floud, Keeper 1947–60, studied at Wadham College, Oxford and the London School of Economics; Hugh Wakefield, Assistant Keeper 1948–1960 and Keeper 1960–75, studied at Trinity College, Cambridge. Elizabeth Aslin studied Fine Art at the Slade, joining Circ in 1947 and rising to Keeper of Bethnal Green 1974–81; Shirley Bury studied Fine Art at Reading University, joining Circ in 1948 and rising to Keeper of Metalwork 1972–85; Barbara Morris studied Fine Art at the Slade, joining the Department in 1947 and rising to Deputy Keeper of Ceramics and Glass in 1976. See: Victoria and Albert Museum, ‘Obituary of Peter Floud, CBE’. Accessed December 12, 2010.; Victoria and Albert Museum, ‘Obituary of High Wakefield’. Accessed March 2, 2011; Aslin, Elizabeth Mary. Who Was Who. A&C Black, 1920–2008 and Online Edition, Oxford University Press, December 2007. Accessed February 24, 2012. www.ukwhoswho.com; Hughes, Graham. ‘Obituary: Shirley Bury’. The Independent, April 4, 1999. Accessed 11.1.12; Victoria and Albert Museum, ‘Obituaries of Shirley Bury’. Accessed December 12, 2010. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/15/23. Wakefield, Hugh, ‘The Circulation Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum’ in Handbook for Museum Curators, Part F, Temporary Activities, Section 1, Circulating Exhibitions, edited by Hugh Wakefield and Gabriel White. London: The Museums Association, 1959: 7–17. ↩︎

-

VAA: Central Inventory 1977. Loose insert memorandum, 77/896, signed Roy Strong, Director [no date]. ↩︎

-

Victoria and Albert Museum. Frayling, Professor Sir Christopher. ‘We Must Have Steam: Get Cole! Henry Cole, the Chamber of Horrors, and the Educational Role of the Museum’. October 30, 2010. Accessed 12.9.11. ↩︎

-

Floud, Peter. ‘The Circulation Department of the Victoria & Albert Museum’. Museum 3.4 (1950) ‘Museums and circulating exhibitions’, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, Paris, UNESCO publication 852: 299. ↩︎

-

Floud, Peter ‘The Circulation Department of the Victoria & Albert Museum’. Museum 3.4 (1950) ‘Museums and circulating exhibitions’, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, Paris, UNESCO publication 852: 299 ↩︎

-

NAL PP.11.H.CW. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation, The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1965–66. London, HMSO: 5 ↩︎

-

NAL PP.11.H.CW. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation, The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1964–65. London, 1965: 5 ↩︎

-

Floud, Peter. ‘Commentary on a Projected International Circulating Exhibition “The Museum, an Educational Centre”’. International Council of Museums, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, WS/101.108, Paris, 30.10.1951. ↩︎

-

NAL 502.M.0848. Morris, Barbara. Inspiration for Design, The influence of the Victoria and Albert Museum. London, 1986:63. From 1909 “When any major collection was acquired, either by purchase, gift or bequest… a proportion of the pieces were set aside for circulation. This practice continued until the Department was closed by the Government in 1976”. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/18/3. English Creamware. London: Victoria and Albert Museum. The exhibition’s 8-page booklet. London, HMSO 10/68. The research acknowledgements for English Creamware are to Mr A. R. Mountford, Stoke-on-Trent Museum; Mr William Billington, Wedgewood Museum; Mr D. S. Thornton, Art Librarian, City Art Gallery, Leeds; Mr Christopher Gilbert, Temple Newsam House, Leeds; Mr R. G. Huges, Derby Museum; Mr Alan Smith, Liverpool City Museum. NAL PP.11.H.CW. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation, The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1966–67. London, 1967: 5/6. ↩︎

-

Drawings by G. B. Tiepolo (1696–1770) from the Print Room of the Victoria and Albert Museum. 1970. Introduction by Graham Reynolds, Keeper, Department of Prints and Drawings, and Paintings. V&A Archive MA/18/3/4. ↩︎

-

NAL PP.11.H. CW. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation, The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1964–65. London, 1965: 7/8. List of Travelling Exhibitions. ↩︎

-

NAL 502.M.0848. Barbara Morris writes on the work of Cheret, Toulouse-Lautrec, Forain, Steinlen, Willette, Grasset, Mucha: “It is a strange irony that these latter posters, now commanding thousands of pounds apiece, were then [1931] regarded as mere ephemera and were not officially registered as museum objects until the 1960s.” In Morris, Barbara. Inspiration for Design, The influence of the Victoria and Albert Museum. London, 1986:193. The Department also pioneered the display of photography as fine art, for example: NAL PP.11.H National Museum Loan Service, School Loans 1966–68, Loans available to Art Schools and Colleges of Education*. Victoria and Albert Museum Circulation Department, HMSO, Grosvenor Press, 6/66. See page 2 for exhibition MP Modern Photography with work by 12 photographers, including Man Ray, Bill Brandt, Ida Kar, Cecil Beaton, Cartier-Bresson. ↩︎

-

NAL PP.11.H.CW. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation, The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1964–65. London, 1965: 8–12. List of Travelling Exhibitions. ↩︎

-

NAL 77.L. National Museum Loan Service, Circulation Department, Victoria and Albert Museum, Exhibitions 1966–67, Exhibitions for Loan to Museums, Art Galleries and Libraries. London, HMSO 1965. ↩︎

-

NAL/77/L. National Museum Loan Service, Circulation Department, Victoria and Albert Museum, Exhibitions 1966–67, Exhibitions for Loan to Museums, Art Galleries and Libraries, HMSO 1965. C26 Tiles: ‘Middle East and Europe, 1200 to present day; Persian, Turkish, Syrian; Hispano-Moresque, Italian Renaissance, German, Dutch, English. Lustre tile from Rayy, Persia; early 15th century tile from the Green Tomb of Sultan Mehmet I, Bursa; Italian maiolica from Petrucci Palace, Siena and Church of San Francesco, Forli.’ ↩︎

-

Morris, Barbara. Inspiration for Design, The influence of the Victoria and Albert Museum. London, 1986:185. ‘Since the end of the Second World War, largely as a result of the efforts of the Goldsmiths Company, a much more original approach to silver design has emerged, a trend that has been encouraged by the Museum in commissioning pieces from leading silversmiths to add to the permanent collections.’ ↩︎

-

Morris, Barbara. Inspiration for Design, The influence of the Victoria and Albert Museum. London, 1986:116. ‘There is little doubt that the exhibition of Victorian and Edwardian Decorative Arts in 1952, which was the first post-war exhibition to focus attention on the textiles of William Morris, was responsible for the reprinting of Morris’s designs by Sandersons and other firms’; ‘Two exhibitions of English chintz played a vital part in revitalizing the British textile industry: the first was assembled by the Circulation Department of the Museum at the Cotton Board, Manchester, in 1955, and entitled English Chintz: Two Centuries of Changing Taste (later circulated in reduced form)… As an article in The Ambassador, the leading British export magazine, stated, the first exhibition traced the development of printed furnishing fabrics over two hundred years and stressed the world influence of British designers; the show was ‘very closely studied by the industry, its designers, students and general public’ and was widely reported throughout the world.’ ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/15/17. Note from Hugh Wakefield, Keeper of Circulation Department to Mr Hodgkinson, for the Director, dated 5 March, 1965. ↩︎

-

Victoria and Albert Museum. Video clip ‘My V&A: Peter Blake’. Accessed September 1, 2011. Peter Blake recounts his time studying at the RCA in the V&A from 1953–56: “the cafe was tiny, I can’t remember which room it was in, but all around the walls were the original Beggarstaff Brothers posters, so we’d sit at the table next to the Don Quixote, that wonderful Don Quixote, I mean you could touch it, you could touch the paper, I think that that was only for a couple of years and it was quickly put behind glass” [author transcript]. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/1/1. Victoria and Albert Museum, Circulation Department, Material Available for Loan to Art Schools and Teachers’ Training Colleges,1951–2. London, 1951: 2. The Circulation Department Art School Prospectus archive is split across holdings at VAA Blythe House (MA/17/1) and the NAL (Periodicals PP.11.H) with records for 1948–51 and 1952–53 absent from both. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/1/1. Victoria and Albert Museum, Circulation Department. Material Available for Loan to Art Schools and Teachers’ Training Colleges,1951–2. London, 1951: 2. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/1/1. Victoria and Albert Museum, Circulation Department. Material Available for Loan to Art Schools and Teachers’ Training Colleges, 1951–2. The sections are listed as follows: The Decorative Arts in England; Non-European Decorative Arts; Drawings, watercolours, etc; Engravings, etchings, lithographs, etc; Illuminated Manuscripts; Printing and Typography; Book-production; Book Illustrations; Commercial Printing; Colour Process Sets; Calligraphy; Furniture and Interior Decoration; Textiles; Ceramics; Sculpture; Metalwork; Miscellaneous. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/1/2. Victoria and Albert Museum, Circulation Department. Material Available for Loan to Art Schools and Teachers’ Training Colleges, 1953–1954. The order is as follows: Drawings; Watercolours; Graphic Art; Books, Lettering, Printing; Printing and Typography; Book-Production; Textiles; Sculpture, Ceramics; Decorative Arts etc; Metalwork, Costume and Miscellaneous. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/1/5. Victoria and Albert Museum, Circulation Department. School Loans 1959–1960. London, 1959. By 1959 Set No. 165 also included proofs by Bawden, Ardizzone, and others. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/1/6.The Victoria and Albert Museum, Circulation Department. School Loans 1962–1963. London, 1962; MA/17/1/2. Victoria and Albert Museum, Circulation Department. Material Available for Loan to Art Schools and Teachers’ Training Colleges. 1953–1954; MA/17/1/1. Victoria and Albert Museum, Circulation Department. Material Available for Loan to Art Schools and Teachers’ Training Colleges, 1951–2; NAL 77.L. National Museum Loan Service, School Loans 1966–68. Loans available to Art Schools and Colleges of Education, Victoria and Albert Museum Circulation Department. London, HMSO, Grosvenor Press, 6/66. The identity of the weavers is given in the 1966 prospectus as ‘50 pieces, Marianne Straub, Peter Collingwood’. ↩︎

-

NAL607.AC.0565. Floud, Peter, Keeper of Circulation. V&A Museum Circulation Department, Its History and Scope. London, V&A, post-1949: 4. On photographic insert. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/1/1. Victoria and Albert Museum, Circulation Department. Material Available for Loan to Art Schools and Teachers’ Training Colleges. 1951–2. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/1/3. The Victoria and Albert Museum, Circulation Department. School Loans, 1956–57. London, 1956:3. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/1/3. The Victoria and Albert Museum, Circulation Department. School Loans, 1956–57. London, 1956: 4. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/1. The Victoria and Albert Museum, Circulation Department. School Loans 1963–1964. London, 1963: 8. ↩︎

-

NAL PP.11.H.CW. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation. The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1964–65, School Loans. London, 1965:13–19. ↩︎

-

NAL PP.11.H.CW. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation. The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1966–67. London, 1967: 32–37. Appendix: School Loans Conference held at the V&A 20.6.67, report by Carol Hogben. ↩︎

-

NAL PP.11.H.CW. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation. The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1966–67. London, 1967: 35. Appendix: School Loans Conference Report. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/7. Victoria and Albert Museum Circulation Department. Loan Collections 1968–70. London, 1968. Available to Colleges and Schools of Art, Colleges of Education, University Departments, and other Further Education Institutions. Examples of the Circulation Department acquisitions are Print, Josef Albers. Museum no. CIRC.100–1968 and Print, Josef Albers. Museum no. CIRC.110-1968. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/7.Victoria and Albert Museum Circulation Department. Loan Collections 1970–72. London, 1970. National Museum Loan Service, Available to Colleges and Schools of Art, Colleges of Education, University Departments, and other Further Education Institutions; MA/15/5. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation. The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1972–73. Lists these venues: Basingstoke Willis Museum, Bath Victoria Art Gallery, Belfast Ulster Museum, Bristol City Art Gallery, Norwich University of East Anglia, Plymouth Museum and Art Gallery, Rottingdean Grange, St Helens Central Library, Scunthorpe Borough Museum and Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/15/5. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation. The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1972–73. London, 1973: 14–18. ↩︎

-

Floud, Peter, Keeper of Circulation. V&A Museum Circulation Department, Its History and Scope. London, V&A, Curwen Press post-1949: 3. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/6/15. Victoria and Albert Museum Circulation Collections, Register of Acquisitions No. 15. CIRC.51.1947 Coloured lithograph, ‘Village on a River Bank’, Paul Signac, 6,500 francs, £13 10s 10d, purchased by Peter Floud from R. G. Michel, 17 Quai St Michel, Paris. Purchase form dated 23 September 1947, acquisitions entry 3 October 1947. CIRC.51-1947 to CIRC.70-1947. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/6/15. Victoria and Albert Museum Circulation Collections, Register of Acquisitions No. 15. For example, contemporary fabrics presented by Heal’s Wholesale & Export Ltd, 196 Tottenham Court Road, London W1, about 1939. Museum no.s CIRC.209 to 214-1947 and Graham Sutherland, ‘Sutherland Rose’, 1946, purchased for 9s8d from Helios Ltd, Bolton, Lancashire. Museum no. CIRC.71-1947. VAA: MA/6/15. Victoria and Albert Museum Circulation Collections, Register of Acquisitions No. 15. CIRC.93 to 98-1948 were four purchases and two gifts of designs by Tibor Reich for Tibor Ltd, Clifford Mills, Stratford-on-Avon. ↩︎

-

Not all CIRC. acquisitions were for travelling, for example CIRC.758-1969 comprised the Strand Palace Hotel Foyer, by Oliver P. Bernard for F. J. Wills, architect, illustrated in The Burlington Magazine Vol. 120, No. 902, Special Issue Devoted to The Victoria and Albert Museum (May, 1978): 274 to accompany Strong, Roy. ‘The Victoria and Albert Museum – 1978’.The Burlington Magazine Vol. 120, No. 902 (May, 1978) and then proposed for the Twentieth Century Primary Gallery, later featured in Art Deco. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2003. Accessed October 20, 2011. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/28/85/1 (formerly ME/29/42). Victorian and Edwardian Decorative Arts, 1949–1953, Part 1. Typewritten memorandum: Peter Floud to Director, Leigh Ashton, dated 27 October, 1951, Leigh Ashton’s memorandum in response was sent to Woodwork, Metalwork, Ceramics, and Textiles and asked that ‘where Departments are offered as gifts or for purchase material produced during the period 1852–1952, which though possibly unsuitable for permanent retention in the Museum collections, should be considered for inclusion in the Exhibition [then titled ‘100 Years of British Decorative Art: 1852–1952’]… inform Mr Floud in all cases’. ↩︎

-

For example, VAA: AAD MA/28/85/1 (formerly ME/29/42). Victorian and Edwardian Decorative Arts, 1949–1953, Part 1, Typed Minute Sheet from Peter Floud to Director, Leigh Ashton, dated 31 August, 1951, notes ‘opportunities may occur for purchase now at nominal prices of material which will probably be able to command quite substantial prices in the next 10–20 years. An example is the purchase… of 2 important Pugin domestic chairs for £2–10 each.’; Floud, Peter, Victorian & Edwardian Decorative Arts. Small Picture Book No. 34, October 1952:3/4. Introduction, initials ‘P.F.’ for Peter Floud, ‘After having been out of fashion for the past forty years, [i.e. since 1912] Victorian furniture and furnishings are now receiving the attention of the initiated.’ ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/28/85/1 (formerly ME/29/42). Victorian and Edwardian Decorative Arts, 1949–1953, Part 1, Typed Minute Sheet from Peter Floud to Director, Leigh Ashton, dated 31 August 1951, ‘In dealing with material after 1914 one has to make most invidious distinctions between living designers, craftsmen and firms, and any selection would inevitably cause some ill-feeling.’ ↩︎

-

NAL 77.L V&A catalogues 1955–65. Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of English Chintz, English Printed Furnishing Fabrics from their Origins until the Present Day. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, May 18 to July 17, 1960: 1. Introduction by Trenchard Cox, Director, May, 1960. ‘A deliberate attempt has also been made towards the ideal, which is less easily attained, of excluding from the selection all traces of present-day tastes and preferences.’ ↩︎

-

Graves, Alun. In A Grand Design: The Art of the Victoria & Albert Museum, edited by Malcolm Baker and Brenda Richardson. London, 1998: 380. ‘Although the Circulation Department acquired contemporary British tableware during the 1950s, what was collected tended to be quite conservative, following types popular in the interwar period. It was not until the mid-1980s that highly styled and thoroughly contemporary 1950s tableware – like Ridgeway’s “Homemaker” series – was actively collected by the Museum.’ The Department’s innovative display methods for ‘easily replaceable’ contemporary ceramics, on open Perspex shelves, may further explain the focus on ‘popular’ rather than avant-garde styles; see Wakefield, Hugh. ‘Open Display’. Museums Journal (January, 1957): 243. ↩︎

-

NAL PP.11.H.CW. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation. The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1966–67. London, HMSO, 1967: 32–37. Appendix: School Loans Conference held at the V&A 20.6.67, report by Carol Hogben. ↩︎

-

NAL PP.11.H.CW. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation, The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1966–67. London, HMSO, 1967: 36. Appendix: School Loans Conference held at the V&A 20.6.67, Mr Meredith Hawes, Hon Secretary of the Association of Art Institutions and Principal of Birmingham College of Art. ↩︎

-

NAL PP.11.H.CW. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation, The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1973–74. London, HMSO: 5. Travelling Exhibitions. See CIRC.713-1971 and CIRC.517 to 561-1972. ↩︎

-

Rumbelow, Molly. The Victorian Revival. RCA MA dissertation 2003:47. Interview with Barbara Morris, February 2003: ‘If anything was under £10.00 they could borrow from the petty cash and get the money back without questions being asked’. ↩︎

-

Richardson, Brenda. In A Grand Design: The Art of the Victoria & Albert Museum, edited by Malcolm Baker and Brenda Richardson. London, 1998: 385. Dress fabric, Marc Foster Grant, 1973. Museum no. CIRC.189-1974: ‘One day in 1973 there were visitors to Daniel’s class. Staff from the V&A’s Circulation Department were looking for work suitable for “The Fabric of Pop,” a travelling exhibition of Pop imagery in textiles and fashion of the late 1960s and 1970s. In those years, Circulation staff essentially scavenged door to door – often in art schools – to acquire contemporary design works… Grant reports that there was never a question of being paid for these works; the student designers were so excited by the Museum’s interest and the prospect of exhibition that they gave to the V&A whatever the curators liked.’ [At Brighton Polytechnic School of Art and Design.] ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/15/17. Typescript note to the Director (probably by Hugh Wakefield) responding to criticism by Mr Wingfield Digby of the Department’s commission of a Harold Cohen tapestry from Edinburgh Weavers, no date but after 1967. Harold Cohen’s ‘Over All’ tapestry, 1967, Edinburgh Tapestry Company, CIRC.536-1967, was commissioned by the V&A in 1966. ‘I am worried, however, by the suggestion that this Department – whose acquisitions consist almost entirely of examples of modern design and the crafts – should need to refer elsewhere for proper discrimination in these fields. It is surely a very reasonable convention that Departments do not refer directly… For confirmation of their conclusions in matters such as proposals for acquisition, if only because of the compromise of taste and direction which would result.’ Harold Cohen’s work continues to be acquired by the Museum, for example Print, Harold Cohen, May 2003. Museum no. E.263-2005; Drawing, Harold Cohen, 1989. Museum no. E.1047-2008; Drawing, Harold Cohen, 1977 and 1982. Museum no. E.327-2009. ↩︎

-

NAL PP.11.H.CW. Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation. The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1966–67. London, 1967:5/6. See also VAA:MA/15/5, Victoria and Albert Museum, Department of Circulation. The National Museum Loan Service, The Year’s Work, 1972–73. London, 1973:5. Travelling Exhibitions. Dom Sylvester: ‘of a more experimental nature came from the further education service’. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/18/3/6. One such exhibition was: Hogben, Carol (curator). Dom Sylvester Houedard Visual Poetries a Victoria and Albert Museum Loan Exhibition. Travelling Exhibition: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1970. It contained 50 works dating from 1963–70, nine of which were the property of the Lisson Gallery. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/18/3/2. Design in Glass, An exhibition of student work from three British art colleges 1969–70. Showed work by students from Edinburgh College of Art, Stourbridge College of Art, and the Royal College of Art, London. The three colleges were given near equal amounts of exhibition space so celebrating their achievements equally; Morris, Barbara. Inspiration for Design, The influence of the Victoria and Albert Museum. London, 1986: 172. ‘The Museum has encouraged the development of studio glass in this country by building up an extensive collection of both British and foreign modern studio glass and by arranging a series of shows’. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/1/7. Victoria and Albert Museum Circulation Department. Loan Collections 1968–70. London, 1968: 5. Available to Colleges and Schools of Art, Colleges of Education, University Departments, and other Further Education Institutions. PD Product Design: ‘This exhibition consists of approximately forty frames showing the original sketches, notes and working drawings for a number of miscellaneous products, together with photographs etc. of the finished article. Designers represented include Robert Welch, Ronald Carter, Kenneth Grange, Alan Tye and Knud Holscher, whilst the histories recorded include an auditorium chair, a sanitary suite, and a range of stainless steel cutlery.’ ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/17/1/8. Victoria and Albert Museum Circulation Department. Loan Collections 1970–72. London, 1970: 4. National Museum Loan Service, Available to Colleges and Schools of Art, Colleges of Education, University Departments, and other Further Education Institutions. ID Industrial Design International: ‘Shown in six travelling showcases accompanied by thirty framed photographs etc., this exhibition is devoted to industrially-designed objects of domestic scale and use, which have won the equivalent in their own country of a Design Centre Award within the last couple of years. A special set of eighty colour slides can be used at option, and the exhibition is both delivered, installed, and subsequently removed by the Museum’s own staff. (Not available before September 1971.)’MA/17/1/9. National Museum Loan Service, Loan Collections 1975–77. Available to Colleges and Schools of Art, Colleges of Education, University Departments, and other Further Education Institutions. London, 1975: 7. DR Design Review: ‘The objects in this exhibition are all mass-produced consumer items of modest size and, for the most part, domestic use, each one of which has received a major jury-selected award at national level for distinguished design. They range from a desk-top computer to a portable toilet, from stainless steel hollowware to a mountain-rescue collapsible stretcher, from an electronic digital clock to a movie camera. British goods have been specifically excluded, and most of the examples have been directly imported by the Museum for the occasion from seven different countries overseas. The aim has been to provide an opportunity for the student to appraise visual design intentions in a wide variety of product categories…’. Beogram 1202 record player, Jensen for Bang &Olufsen, 1969. Museum no. CIRC.6-1974. ↩︎

-

Reilly, Victoria. ‘V&A tribute to a living artist’. The Sunday Telegraph, January 24, 1971. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/15/17. Typescript, by Hugh Wakefield, dated August 1971, Memorandum on the possibility of Circulation Department providing a service specifically designed for public libraries [following a DES meeting 14.5.1971, ministerial suggestion to Library Councils]. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/19/13. Press Cuttings 1965–77. Vaizey, Marina, ‘National Loan Service’. Arts Review. London (29 January, 1972). ‘There are three separate David Hockney print exhibitions on tour, and top of the pops at the moment is Hockney’s 39 etchings published in 1971 which illustrated Six Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm… In 1964–5, for instance, these consisted of seventy travelling exhibitions and 500 school ‘sets’… larger exhibitions (some 90 at this moment) which go to museums and galleries throughout the country, and the other (some 240) which go to ‘schools… the Circulation Department itself, which is really in some ways an alternative museum, a museum broken up into small, coherent units, and constantly on the road’. VAA: MA/19/13. Press Cuttings 1965–77. Rosenthal, Norman, ‘Circulation’. Spectator (12 February, 1977). ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/19/13. Press Cuttings 1965–77. Rosenthal, Norman, ‘Circulation’. Spectator (12 February, 1977). ↩︎

-

‘Artists oppose V & A cut’ by Our Arts Reporter. The Times (16 December, 1976): 8. ↩︎

-

VVVVAA: MA/19/13. Press Cuttings 1965–77. Nurse, Keith. V&A economy cuts ‘will deprive regions’. Telegraph (10 November, 1976). ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/19/13. Press Cuttings 1965–77. No full reference: cutting of letter from Hugh Adams, Department of Modern Arts, Southampton College of Technology, East Park Terrace, Southampton, headed ‘The museum as a metro-monolith’. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/19/13. Press Cuttings 1965–77. No full reference, article headed: ‘A Disaster For Doncaster’, quoting Mr. John Barwick, Director of Doncaster Museum and Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Nieswand, Peter. ‘Regions versus V and A’. The Guardian (26 November, 1976). ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/19/13. Press Cuttings 1965–77. Rosenthal, Norman, ‘Circulation’. Spectator (12 February, 1977). ↩︎

-

Thornton, Peter, ‘Furniture Studies – The National Role’. The Burlington Magazine Vol. 120, No. 902, Special Issue Devoted to The Victoria and Albert Museum (May, 1978): 284. ‘Fig.19. This chair, made by Rupert Williamson in 1976 and bought by the Department last year as a telling specimen of modern design and craftsmanship, reflects the Museum’s continual concern with advanced developments in taste which has recently been re-affirmed by the Director. The strengthening of the Museum’s representation of twentieth-century design is now a major pre-occupation for all the Departments, the planned twentieth-century Primary Gallery providing an additional incentive.’ W.18:2-1977. The Burlington Magazine Vol. 120, No. 902, Special Issue Devoted to The Victoria and Albert Museum (May, 1978): i-lxxxiv. ↩︎

-

The National Archives. DCMS Sponsored Museums Performance Indicators 2009/10 Accessed September 12, 2011. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/6/74. Acquisitions Register. Misha Black, Ekco mains wireless receiver model Ekco UAW78, made by E. K. Cole Ltd, 1938, purchased for £40 from Norman Jackson, 5 Pyrmont Road, Strand-on-the-Green, London W4. Museum no. CIRC.47-1977. ↩︎

-

VAA: MA/6/74. Acquisitions Register. CIRC.124, A&B-1977, Derek James Fawcett, Nautech Auto-Helm System, 1976, Nautech Ltd, Asser House, Airport Service Road, Portsmouth, Hampshire; for tiller-steered yachts, vane, housing for motor, rod and halyard, DCA 1976. Approved 2 November 1977. ↩︎

-

89 VAA: MA/15/7: Transport Schedules. 7 – 12 November 1977, Minton: Barnard Castle to VAM. The travelling version of the V&A Minton exhibition was prepared by Jennifer Opie but not sent out; source, interview, Joanna Weddell with Jennifer Opie, Geoff Opie and David Coachworth, V&A Research Department, 4.7.12. ↩︎