From 23rd April to 9th November 2012, the V&A will present a small selection of original paintings and drawings by Chiang Yee augmented by archival material, relating to his life in Britain, in the T.T. Tsui gallery of Chinese Art. The display will complement the V&A’s spring exhibition Britain Design 2012, which showcases the far-reaching influence of Britain and British design around the world. The display is generously supported by the Friends of the V&A.

Introduction

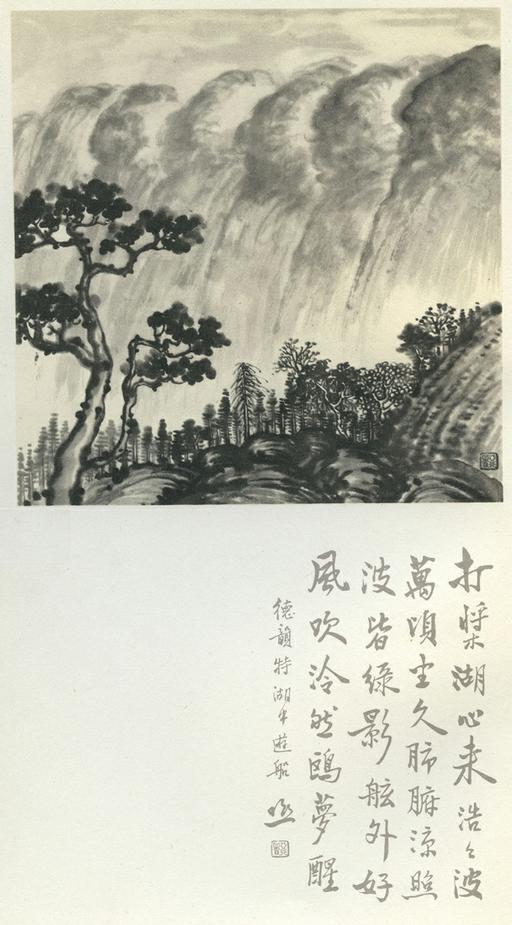

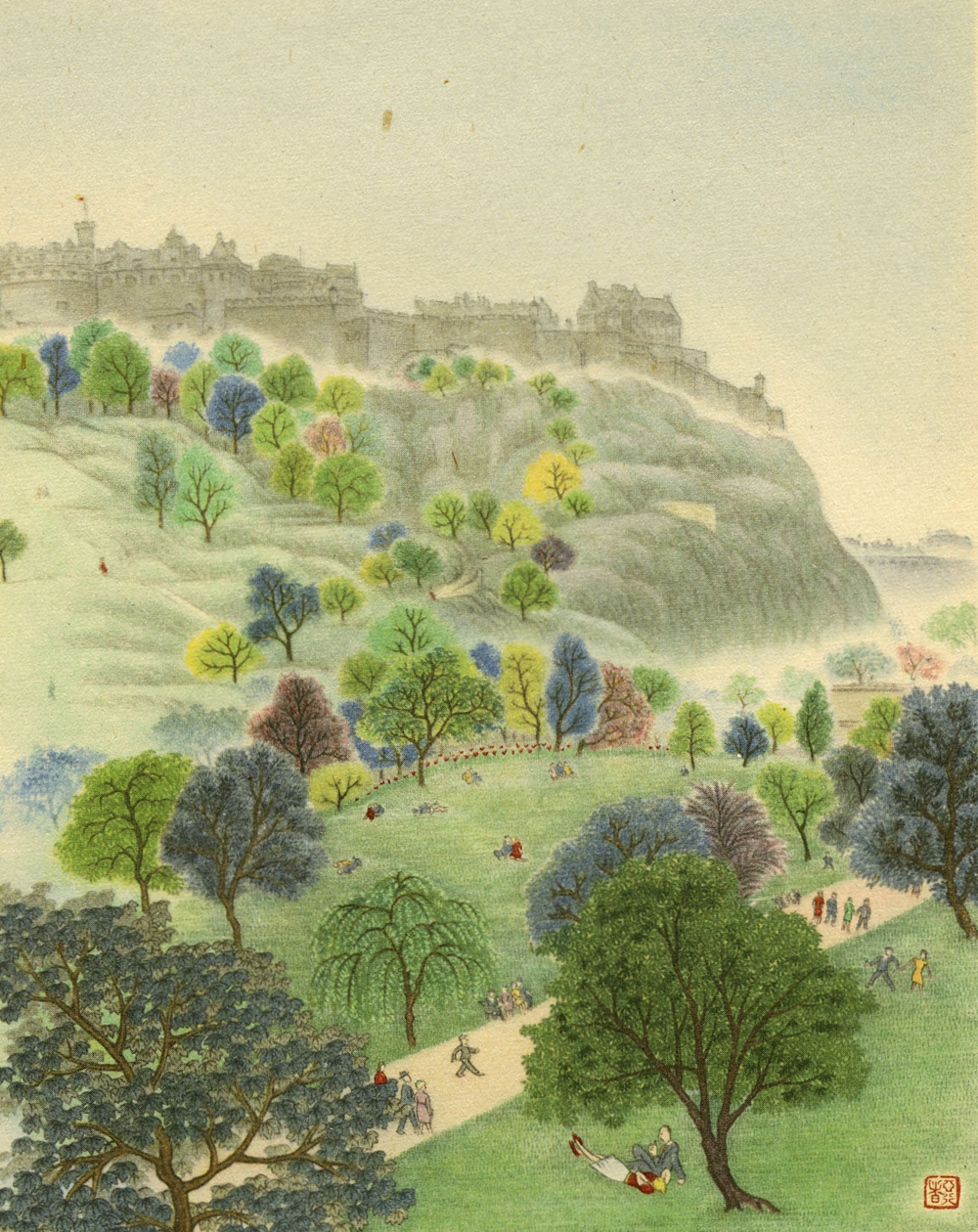

Chinese artist and writer Chiang Yee (1903–1977) came to Britain in 1933, where he lived and worked until 1955. During this time he wrote a successful series of illustrated travelogues using the pen name ‘Yaxingzhe’ or ‘Silent Traveller’.1 The books describe Chiang Yee’s life in London and Oxford during the turbulent years of the Second World War and record his travels to the Lake District, the Yorkshire Dales, Edinburgh and Dublin.2 Illustrated throughout, with his own unique ink and watercolour paintings, sketches and poems, they represent a significant artistic, as well as literary project. Notably among the first Chinese writers to write books in English in the first half of the 20th century, Chiang enjoyed a prolific publishing career in Britain, in which he also published two seminal texts on Chinese painting and calligraphy, memoirs of his childhood in China, and several children’s books.

In addition to his publications, Chiang engaged in a wide variety of other cultural and educational activities, including lecturing on Chinese art, curating and teaching Chinese language at London’s School of Oriental Studies (SOS). As a result he became a widely recognised and consulted authority on Chinese culture in Britain and served as an interpreter of Chinese culture to Western audiences at a time when general and academic interest in China was increasingly keen.

Chiang Yee has received relatively little scholarly attention compared with other influential Chinese figures of the same period, who also acted as cultural intermediaries, such as Lin Yu Tang, Lao She and Fu Lei.3 However, in recent years renewed interest in Chiang Yee has generated some significant new research on his life and work, in particular by Chinese American scholar Da Zheng, author of a detailed biography of Chiang Yee.4

This paper builds on the growing body of research on Chiang Yee, to consider him in a specifically British context; evaluating his life and work in Britain and acknowledging the significant contribution he made to the presentation and understanding of Chinese art and culture in Britain. This paper offers an analysis of Chiang’s books on Chinese art, the Silent Traveller books and the various cultural activities he engaged in between 1933 and 1955; looking not only at his personal achievements, but also at the broader implications of his life and activities, as indicators of a wider cultural shift in Britain in terms of attitudes to, and relationships with China, its people and culture, during the first half of the 20th century.

Chiang Yee in China

Chiang was born into a wealthy, middle-class family in the district of Jiujiang in Jiangxi province, south-west China, in 1903.5 His father was a successful portrait artist and he indulged Chiang’s early interest in painting and calligraphy, practices which were to become lifelong pursuits. He enjoyed the privilege of a classical education based on Confucian teachings in early childhood and later studied a broader range of subjects including Maths, Physics and Chemistry, following modernist educational reforms in China in the first decades of the 20th century.6

In 1924, Chiang married his first cousin Zeng Yun to whom he had been betrothed since birth. The loveless marriage, though deeply unhappy, nevertheless produced four children. He graduated with a degree in Chemistry from South Eastern University in Nanjing in 1926 and taught for a short period before joining his elder brother in the National Revolutionary Army. He then went on to take up a variety of roles in local government in and around Jiangxi, culminating in the post of local magistrate in his native city of Jiujiang in 1929.7

During his short career in local government Chiang cultivated a personal image and lifestyle based on that of a traditional scholar official. Although much of his time was spent attending to government business he also dedicated himself to the scholarly pursuits of painting, poetry and calligraphy. His love and pursuit of scholarly ideals, instilled in him during his early education, endured throughout his life and characterised his subsequent painting and writing career. In a letter to his closest friend Innes Jackson in 1936 he wrote, ‘You know I had a great love in the past literary men’s life of my country. I have read the records of them all. I always wanted and dreamt to be one like that’.8

Despite his devotion to these cultured pastimes, Chiang was burdened by the professional challenges he faced in his government work. He resigned from his post as magistrate in 1931, disillusioned by the corruption and nepotism that characterised local politics and government. He was not only disheartened by his career prospects, but also by his marriage and the increasingly unstable political situation in China; fraught by a bloody civil war and the persistent threat of Japanese aggression. All these factors ultimately contributed to his decision to leave China.9 In 1933 Chiang left his wife and children in the care of his elder brother and sailed from Shanghai to Marseille and then on to London, where despite his poor English, he hoped to forge a new career.

The Chinese diaspora in 20th century Britain

Life in early 20th century China was characterised by chaotic upheaval as the country was torn apart by violent struggles for political power following the end of imperial rule in 1911. In the midst of this turmoil there were calls for social change, which engendered a powerful movement to reinvigorate Chinese culture and establish a modern identity for China. This movement transformed the fields of literature and art as Chinese people searched for new modes of self expression.10 Following the end of the First World War, in 1918, many Chinese artists and intellectuals attempted to secure opportunities to study in Europe and America.11 Artists hoped to study Western artistic traditions and appreciate Western art works first hand; others hoped to learn about politics, law, science and literature from a Western perspective and bring new ideas back to China.

When Chiang arrived in Britain in 1933 there was already a small but significant Chinese community in the UK, concentrated in Liverpool and London. It had been established in the late 19th century and the 1931 UK census recorded 1934 Chinese-born residents living in England and Wales.12 Many were employed as sailors in the British Merchant Navy, whilst others worked in laundries, shops and restaurants. Despite the long-standing presence of Chinese communities in early 20th century Britain, popular perceptions of Chinese people were commonly based on sensationalist stories, put forth in the press and caricatured stereotypes presented in the popular media; the Chinese were variously described as sly, untrustworthy characters who smoked opium. These negative stereotypes were embodied by Sax Rohmer’s popular fictional character Dr Fu Manchu and Oscar Asche’s Chu Chin Chow.13

During the first decades of the 20th century there were very few Chinese scholars and intellectuals in Britain, but throughout the inter-war years their numbers grew, as more people looked outside China for intellectual inspiration as well as political refuge. Most of those who came to study abroad eventually returned to live in China but some, including Chiang Yee stayed to make a life for themselves whether or not they had initially intended to do so. Following his arrival in Britain, Chiang quickly integrated into this small intellectual community. He shared a flat in Hampstead with a Chinese author and playwright Hsiung Shi-I, who made a name for himself in Britain with his 1934 play, Lady Precious Stream, an exotic tale of romance and intrigue set in imperial China. It became a West End hit and a staple of amateur dramatic societies throughout the country for many years afterwards. Hsuing introduced Chiang to many influential contacts in London including not only other Chinese living in Britain and visiting from Europe, but also notable figures in London’s art and literary circles.14

Although very few Chinese artists came to study at London’s art schools (preferring to study in Paris and Berlin), Chiang still received many distinguished artists as guests at his Hampstead home, including Xu Beihong (1895–1953) and Liu Haisu (1896–1994).15 When Xu visited London Chiang often accompanied him to museums and galleries. He recounts one of these trips in The Silent Traveller in London, writing ‘I used to accompany Professor Ju Péon [sic], a Chinese artist, while he was copying one of Raphael’s Seven Cartoons in the Victoria and Albert Museum’.16

Following studies in Europe, both Liu and Xu went on to promote the work of modern Chinese artists in the West, staging exhibitions in Europe and America. In 1935 Chiang worked with Liu to mount An Exhibition of Modern Chinese Painting at the New Burlington Galleries. Liu brought works by many of his students and contemporaries in China to display in this exhibition and also invited Chiang to submit some of his own works.17 The works he submitted were traditionally Chinese in style and subject, executed using Chinese materials and techniques and this was notably one of the few occasions on which Chiang’s work was formally displayed alongside that of other Chinese artists.

At this time exhibitions and surveys of Chinese art generally stopped short of the 20th century, giving added significance to the exhibitions of modern Chinese paintings arranged by Xu and Liu. These exhibitions were important not only in identifying continuity in Chinese art and its production in China, but also in demonstrating that China was a modern nation with a thriving modern culture.

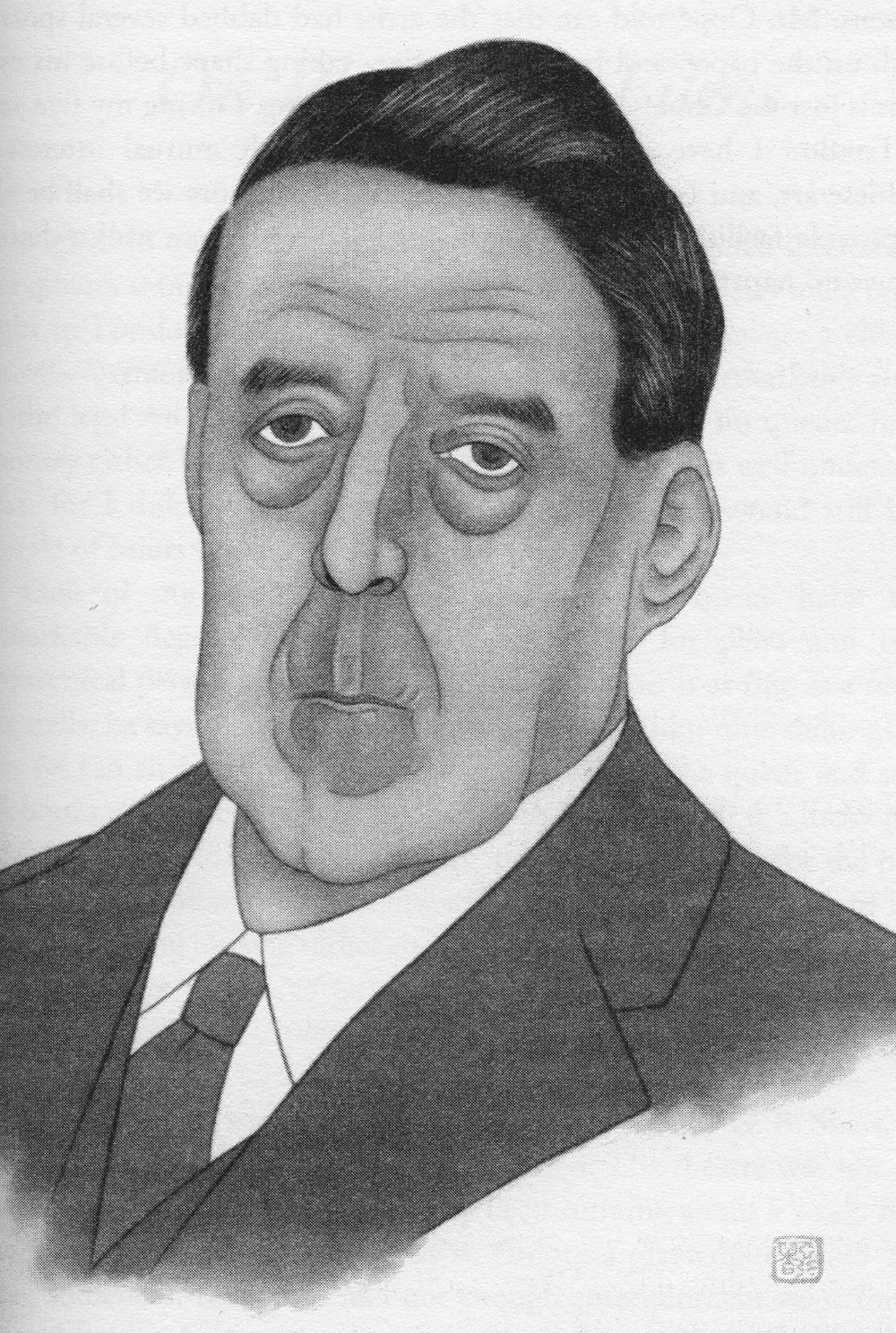

Chiang was acutely aware of the value of social and professional connections and he was an enthusiastic networker. After an introduction to Reginald Johnston, then head of the Chinese department at London’s School of Oriental Studies (SOS), Chiang secured a post teaching Chinese language at the University which he held from 1935 to 1938.18 Throughout the years that he lived in London Chiang made many more influential friends and acquaintances including W. W. Winkworth, Laurence Binyon, Herbert Read, Roger Fry and George Eumorfopoulos. Keen to demonstrate his associations and encounters with London’s intellectual and social elite, Chiang made special mention of many of these relationships in his subsequent travelogues, often accompanied by portrait illustrations.

New directions

Chiang Yee came to Britain with no directly transferable profession and soon turned to painting and illustrating as a means of survival. One of his first commissions, in 1934, was to provide illustrations for Hsiung’s play, Lady Precious Stream, when it was published in book form, shortly after its stage success. Later that year Chiang exhibited some of his works in a fundraising exhibition organised by an eccentric society for the protection of trees known as ‘Men of the Trees’.19 Despite the relative obscurity of the exhibition, one of the works he submitted (depicting trees in a Chinese style) was illustrated in the London Evening Standard, which quickly brought his work to general public attention.20 In the years that followed this exhibition, having recognised the timely opportunity to exploit renewed Western fascination with China, Chiang painted prolifically. He initially focused on traditional Chinese subject matter and techniques before slowly broadening his repertoire to include local British subjects. By 1936 he had staged his first solo show entitled, An Exhibition of Modern Chinese Pictures and Fans by Chiang Yee, at a commercial gallery in Knightsbridge.21

Chiang’s paintings, though undeniably valuable, have never been ranked alongside those of the modern masters of Chinese painting such as Liu and Xu. Nevertheless, he did successfully sell a large number of his works through commercial galleries and he relied on the income this generated for his livelihood; though it was a practice which many Chinese artists at the time would have rejected as vulgar. Chiang himself wrote in the introduction to his book The Chinese Eye: ‘From the very beginning painting has never been a profession: the practisers of it have even been ashamed to sell their works for money’.22 Despite this scholarly ideal of anti-commercialism, in reality many artists openly engaged in the sale of their works.23

Chinese art in Britain

Luxury goods from China have been a familiar presence in Britain’s material landscape since the 17th century. However, it was not until the late 19th century that intellectual opinion began to consider Chinese objects as art, and for many years they remained confined to displays of ethnographic material in British museums or as part of the elegant furnishings and interior decoration of stately British homes.24

During the 19th century and early 20th centuries, serious scholarship on Chinese art began to develop, though the decorative arts, and especially Chinese ceramics, were privileged above all other media. Although scholarship on China was gaining momentum in academic circles at this time, Chinese art remained unfamiliar and little understood by most people in Britain well into the 20th century. Indeed, the persistent vision of China as a romantic, ancient empire, established in the preceding centuries, lingered on in the collective British consciousness. Throughout the early 20th century it continued to inform general attitudes towards China, and Chinese art, whose alien subjects, forms and materials, though appreciated for their exoticism, were rarely understood in their proper cultural context. By the 20th century these visions had also come to symbolise China’s stagnation and well as its continued, ‘otherness’, especially when compared with industrialised Western nations.25

In 1925, The Burlington Magazine published a ground breaking monograph on Chinese art, presenting the first academic survey of Chinese art, as it was understood in Britain at the time.26 The introduction was written by Roger Fry; in it he describes the challenges that were faced by Western cultures in their attempts to understand and interpret Chinese art and culture. He writes, ‘I believe many people may be acquainted with some aspects of European art who still feel the art of China strange to them. For them to come upon a book like this [the Burlington monograph] is to come upon a world to which they have no key.’27 Fry goes on to argue that the lack of cultural contextual knowledge for understanding Chinese art on the part of most Western audiences is what prevents them from penetrating its deeper meanings and significance.

During the interwar years, British scholarship on Chinese art was progressed significantly by a growing number of scholars actively studying and researching Chinese art.28 These included both museum professionals and private collectors, such as Sir Percival David, George Eumorfopoulos, Arthur Waley, Laurence Binyon and W. P. Yetts, to name but a few.29 Between them their expertise ranged from Chinese painting and sculpture to ceramics and decorative arts.

Outside museums and arts societies, formal studies of Chinese art were slow to become established in Britain. Universities prioritised the provision of basic language training for businessmen, missionaries and foreign office officials over cultural studies and it was not until 1930 that the first lectureship in Chinese Art and Archeology was created, at the SOS.30

Exhibiting China: The International exhibition of Chinese art, Burlington House, 1935

Public awareness and general interest in Chinese art was heightened considerably by the landmark International Exhibition of Chinese Art, at Burlington House in 1935. The Exhibition was directed by Sir Percival David, in collaboration with the Chinese Nationalist government and an extensive committee of international experts and collectors. It included over 3,000 examples of Chinese painting, sculpture and decorative arts, of which over 800 were loaned by the Chinese government.31 This collaboration with the Chinese government greatly enriched the academic content of the exhibition and resulted in a more complete survey of Chinese art than any previously seen in Britain. According to David, the exhibition aspired to:

… illustrate the culture of the oldest surviving civilisation in the world. The culture itself is so composite, so esoteric and so storied in its long tradition that it is difficult at once to glean from it a simple significance. Yet the significance exists… the scope of the exhibition is wider and more ambitious than any of its brilliant predecessors. An endeavour has been made to bring together as far as possible, the finest and most representative examples of the arts and crafts of China from the dawn of its history to the year 1800.32

Despite the somewhat patronising language used by David in this excerpt, which appears to reinforce Imperialist views of China as an exotic and esoteric ‘other’, the exhibition played a vital role in introducing the British public to a very broad presentation of Chinese art, such as had never been seen before in Europe.33 Media frenzy ensued during the weeks leading up to the arrival of the British warship sent to collect exhibits from China, and the eventual opening of the show. The exhibition was a resounding success; it was seen by almost half a million people and marked a pivotal turning point in public awareness and appreciation of Chinese art, as well as attitudes to China more generally.

New literature on Chinese art

The interest generated by the 1935 exhibition presented writers and publishers with an excellent opportunity to produce new literature on Chinese art, and numerous books on the subject were published to coincide with the show. Despite the involvement of several Chinese experts on the general organising committee and the significant number of loan objects from China, only one of these new publications was written by a Chinese author; Chiang Yee. Prior to the Burlington exhibition almost all literature on the subject of Chinese art in English had been written by Western authors with few contributions by native Chinese experts. Consequently, London publishers Methuen sought to find a Chinese writer to author a new book on Chinese art, and following a recommendation from Hsiung Shi-I, Chiang was asked to write a book on Chinese painting.34

The Chinese Eye: An interpretation of Chinese painting, was Chiang’s first book. It is divided in to eight chapters and illustrated with 24 black and white images of masterpieces of Chinese painting. The first chapter provides a succinct historical background within which to contextualise discussions in the succeeding chapters about painting’s intimate relationship with both literature and philosophy. The remaining chapters introduce the subjects of Chinese painting and elucidate the importance of inscriptions; and the last chapters describe the traditional materials and tools of the Chinese artist. All of this is achieved in 230 pages in a style that is at once simple and informative. The book fulfilled a vital role in demystifying Chinese art as a practice and a subject for study, which at the time was unknown to most people in the West. It offered readers an introduction to the fundamental principles of Chinese painting and a clearly defined cultural context within which to appreciate it. The book was not intended to be an academic study of Chinese painting, but offered a more accessible approach based on the personal experience and perspective of a practising Chinese artist.35

A small volume entitled Chinese Art was also published to coincide with the International Exhibition, with a chapter on painting by Laurence Binyon.36 In it he describes the importance of understanding Chinese views and approaches to Chinese art, and painting in particular:

If we are truly to appreciate any work of art it is idle to approach it from the outside, bringing with us all our prejudices and preconceptions. We must try to enter into the mind of the man who made it, discover what his aim was and consider how far he has achieved his aim. In the case of Chinese painting, produced by a race so remote from Europe, while it is easy to enjoy the decorative qualities presented by its surface, we cannot understand it without some knowledge of the Chinese conception of picture making, of the Chinese painter’s approach to his subject, and the mental background behind his art.37

This is exactly the viewpoint and important context that The Chinese Eye provided; capitalising on the authority and authenticity that Chiang was able to bring to the book as a Chinese artist himself. It was the first major publication on Chinese painting written in English by a Chinese author and marked the beginning of a period in which Chinese intellectuals were, for the first time, able to communicate information and ideas about their culture to Western audiences directly, without mediation by Western writers.38 The book was met with critical acclaim from the general public as well as the academic community. Art critic Herbert Read wrote of it, ‘… he has explained the Chinese conception of art so clearly and thus enabled us to appreciate its qualities with a true aesthetic understanding’.39 Laurence Binyon also reviewed Chiang’s book, writing, ‘this book tells much in small compass, and to all who take an interest in Chinese painting, and want to know more about its essential qualities, it will be an initiation.’40 The Chinese Eye identified Chiang as a respected authority on Chinese painting and marked the beginning of his prolific publishing career.

Following the success of this publication, Chiang quickly became established on London’s art and literary scene as a lecturer and commentator on Chinese art and culture. During the Burlington House exhibition, Chiang gave a series of lectures on the principles and techniques of Chinese painting at SOS, which were well received and even included the renowned collector George Eumorfopoulos among the participants.41 Throughout the 1930s and 1940s Chiang was regularly invited to contribute to BBC radio programmes, despite initial concerns about his strong accent, to discuss Chinese art, poetry and literature.42 He was also a regular speaker on the circuit of various London societies and charitable events as well as at literary festivals.43

In 1938, Chiang went on to write a complementary volume on Chinese art, this time on Chinese calligraphy. A similarly insightful and accessible introduction to the art and practice of calligraphy in China, Chinese Calligraphy was the first single volume in English dedicated to this then little understood subject matter and was significant in bringing this art to the attention of the wider public.44 The book describes the origins of the Chinese writing system, introduces various styles of calligraphy, and devotes four chapters to expounding practical techniques and the art of composition. The remaining chapters discuss the aesthetic beauty of calligraphy and its relationship to the arts of painting, literature and philosophy. It is illustrated throughout with ideograms and examples of calligraphy, by Chiang and known masters of the tradition. Ultimately the book allowed those without any knowledge of the Chinese language to understand and appreciate the refined beauty of Chinese calligraphy, its relationship to other art forms and its revered status in Chinese culture. It was reprinted in several subsequent editions and met with enthusiasm by reviewers, with comments including ‘[…] no praise is too high for this book, which is at once instructive and delightful. It is emphatically commended to all lovers of Chinese art.’45

The Silent Traveller

Chiang Yee’s illustrated travelogues represent his most significant commercial and artistic success. Informative, thought provoking and unusual,they found a wide readership among Anglophone audiences around the world and are still enjoyed by readers today.46

The appeal of The Silent Traveller books lies not only in their unfamiliar aesthetic beauty, but also in their novel approach to recording Chiang’s particular experiences of Britain, ‘from the point of view of a homesick Easterner’.47 They offer a unique perspective on Britain, through the eyes of a Chinese exile at a time when Western literature about China was common, but books about the West by a Chinese author were exceptionally rare. In this way they challenged traditional conventions of travel writing taking Britain as their ‘exotic’ subject matter. The books provide an intimate exploration of Britain with detailed descriptions of British culture, society and landscape, delivered with poetic prose and perceptive illustrations.

A Chinese Artist in Lakeland: The modern expression of national tradition

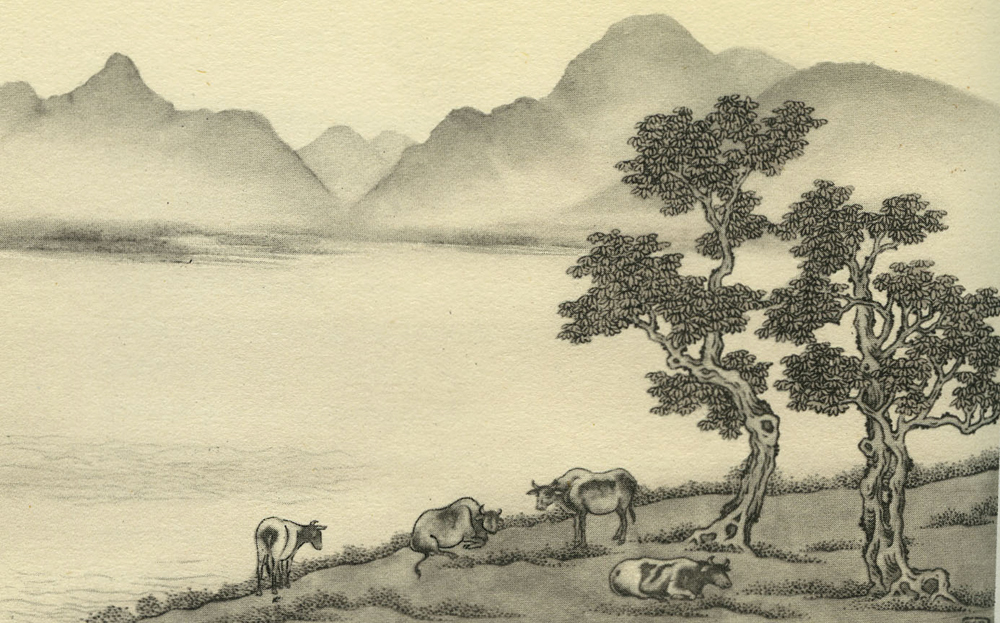

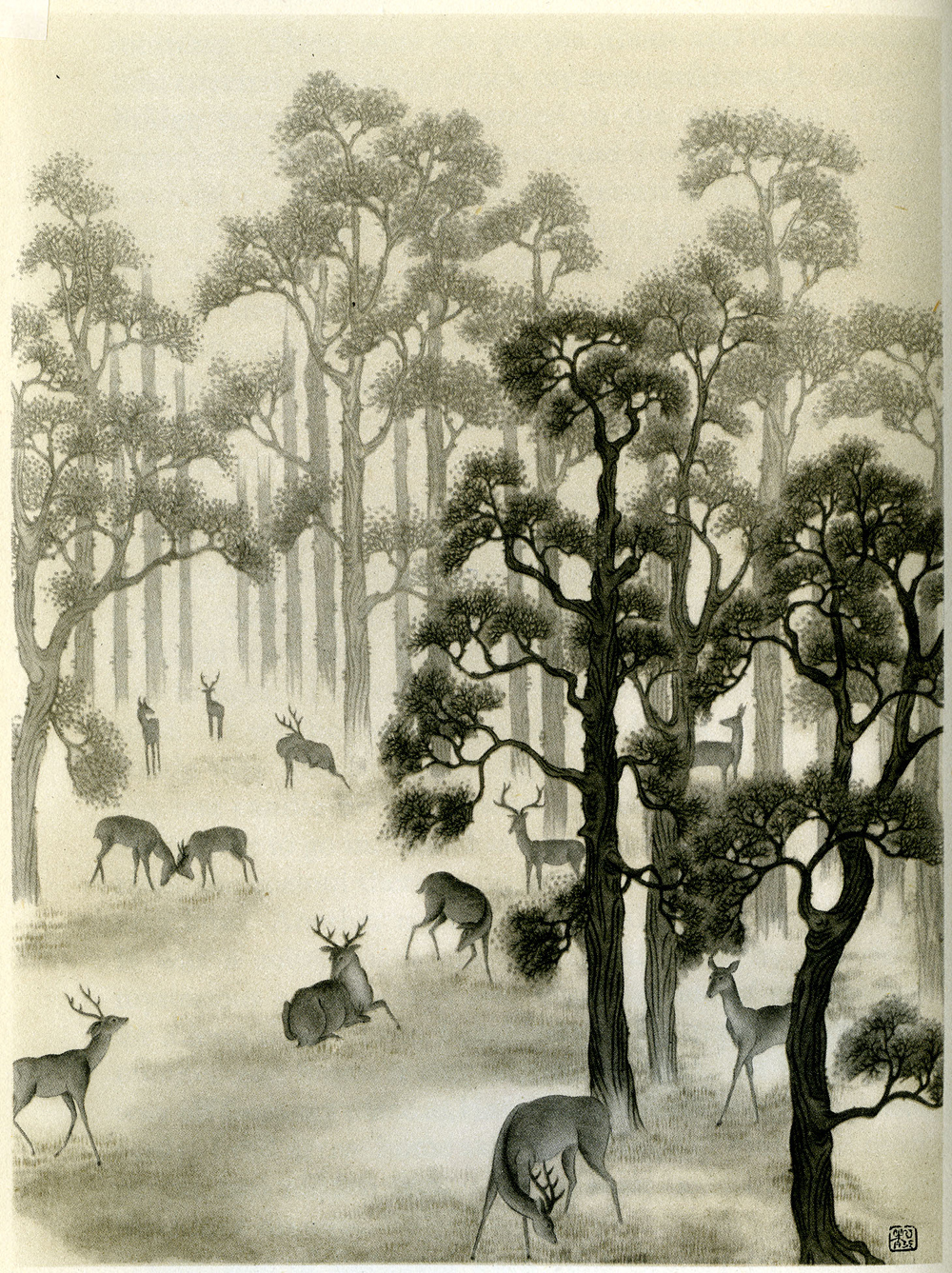

In 1937 the first of the Silent Traveller books was published, under the title, The Silent Traveller: A Chinese Artist in Lakeland. It is a slim volume of just 67 pages divided into five chapters, each dedicated to a different Lake area and describes Chiang’s two week journey through the region, in 1936. Using a combination of detailed, descriptive narrative and 13 monochrome illustrations, he conveys the distinctive character of the landscape and the people in each place he visits. For Chiang, the Lake District held particular appeal as a subject for his first travelogue because of the region’s historical associations with several of Britain’s literary and artistic elite, including Wordsworth, Constable and Turner. Chiang saw a connection between the activities of these artists and the traditions of China’s literati, in terms of their common love of natural beauty and their efforts to capture it, which he felt transcended cultural boundaries. In this book Chiang makes his own contribution to the artistic legacy of the Lake District.48

Chiang’s illustrations of Britain were executed using traditional Chinese materials; ink, brushes and absorbent paper, and he applied many of the principles of Chinese painting to them; though he says he did ‘not set out to turn the British scene into a Chinese one’, rather ‘to interpret British scenes with my Chinese brushes, ink and colours, and my native method of painting’.49

Recognisably Chinese in style the illustrations succeeded in capturing the particular character and atmosphere of the landscapes in the Lake District, with striking and unusual results. In the preface to The Silent Traveller: A Chinese Artist in Lakeland, Herbert Read identifies Chiang as, ‘a master of the art of landscape painting’ and his art work as ‘… the modern expression of national tradition’.50

Although Chiang openly acknowledged the ‘different flavour’ of his illustrations he did not want them to be appreciated simply on the basis of their ‘Chinese’ character.51 Chiang’s artistic aims lay in capturing the essence of what he saw, not in identifying his work with the Chinese tradition or otherwise, which he saw as an arbitrary exercise. He writes,

…most people nowadays know something about the general appearance and subject matter of Chinese paintings. Unfortunately, they are apt to be biased. If they see a picture with one or two birds, a few trees or rocks piled together, they will certainly say that that is a lovely Chinese painting. But if they see anything like Western buildings or a modern figure there, they will suddenly say “that is not Chinese”. In this book I have painted from the surroundings in which I have lived these last few years, and I hope my readers will not be so biased as to say that they do not like the paintings because they are not “Chinese”. And I also hope some of my readers are not biased in another way and will not say that they like this painting because it has a Chinese flavour. I should like them to criticise my work without preconceptions.52

Chiang breathed new life into many of Britain’s most iconic landscapes and landmarks in a unique style that allowed them to be both instantly recognisable and yet different looking; capturing the essence rather than an exact visual record of the subject. (fig. 4) The ability to capture the atmosphere and spirit of his subjects is arguably indebted to both the use of Chinese media and techniques, and traditional Chinese conventions of painting from memory rather than life; allowing a scene to become imbued with the particular emotional responses of the painter. In the introduction to The Chinese Eye, Chiang writes:

The painter’s aim is to convey an atmosphere, a poetic truth… Whether we paint a small orchid, a young tit or the rugged cliffs of the Yangtze gorges, we must always have some poetic message to convey. If only we can transfer to the mind of the onlooker this fruit of our dreaming contemplation, we have no care for verisimilitude…’53

Regardless of Chiang’s artistic intentions to create works that transcended cultural definition or categorisation, the ‘Chinese flavour’ of his works, which are necessarily created by his choice of materials and methods of working, undoubtedly accounted for much of their particular appeal to Western audiences and the subsequent success of his illustrated travelogues.54

Poetry and prose

Poetry is central to all the Silent Traveller books. Poems written by Chiang and other poets, in both Chinese and English are scattered throughout the text, and many of the illustrations are accompanied by poems written in elegant Chinese script (with English translations). This combination of visual and literary arts reflects the traditional Chinese practice of inscribing poems on paintings. The prose itself also has clear poetic qualities. Describing the morning of a boat trip in the Lake District Chiang writes:

Next I came to the boats’ landing stage; looking across to the other side as far as I could see, the mountain ranges stood out clearly against the blue sky and even the beams of sunlight could be separately counted. The morning smoke was steadily puffing up from the chimney of some house hidden in the mass of trees and only a roof might be hazily discerned through the mist.55

For this quality of the writing Chiang was greatly indebted to his student and friend Innes Jackson, who selflessly reworked and edited the text of this and many of Chiang’s other books, including The Chinese Eye. The book was beautifully produced with high quality plates and Chiang’s name embossed on the spine and front cover in flourishing Chinese characters, adding to the Chinese aesthetic and exotic appeal of the book. It sold out in its first month and was republished in nine subsequent editions.56

Other ‘Oriental’ travellers in London

Despite the relative rarity of such literary accounts of Britain, Chiang’s first travelogue, written in 1937, was not without precedent. At least two other ‘Oriental’ writers had previously written accounts of their lives in London, with varying degrees of illustration.

In 1907, Japanese author artist Yoshio Markino (1869–1956) illustrated a book called The Colour of London with innovative interpretations of London scenes, in a style heavily influenced by traditional Japanese woodblock printing techniques. In 1910 he went on to write and illustrated a travelogue entitled, A Japanese Artist in London.

In 1920, a Chinese law student and journalist M. T. Z. Tyau, also wrote an account of his life in Britain in a book called, London Through Chinese Eyes, though he did not provide any of the illustrations. It is not clear whether Chiang was influenced by, or even familiar with Markino’s work, but he was certainly familiar with Tyau, whose book he quotes several times in The Silent Traveller in London. London Through Chinese Eyes clearly provided inspiration, if not a model for Chiang’s book, not least in terms of its idiosyncratic structure.57 However, although the concept of an illustrated travelogue about Britain, by an Asian author seems not to have been a new one, Chiang’s certainly became the most popular and successful. This was due to the particularly observant and erudite style of the narrative as well as the unique quality of the illustrations, but also because of increased interest in China at the time of their publication.

The Silent Traveller in London

While the Lakes book took the form a travel journal with a clear chronology and sense of journey, Chiang took a much more idiosyncratic approach to his subject in The Silent Traveller in London. It is characterised by themed ruminations on a wide variety of seemingly trivial subjects such as the weather, teatime, children, books and the theatre. The book is divided in to two parts. Part one takes the reader on an alternative tour of London exploring the unique character of the city in each of the four seasons. Part two examines London life and society; describing museums and galleries, parties and people, habits and customs, all in intimate detail with a combination of sharp observation and conversational charm. The Silent Traveller in London represents one of Chiang’s most intimate portraits of Britain as it was his home for over seven years and the first British city of his acquaintance. The narrative not only provides detailed descriptions of the city, but also describes many of the personal relationships that coloured his life there.

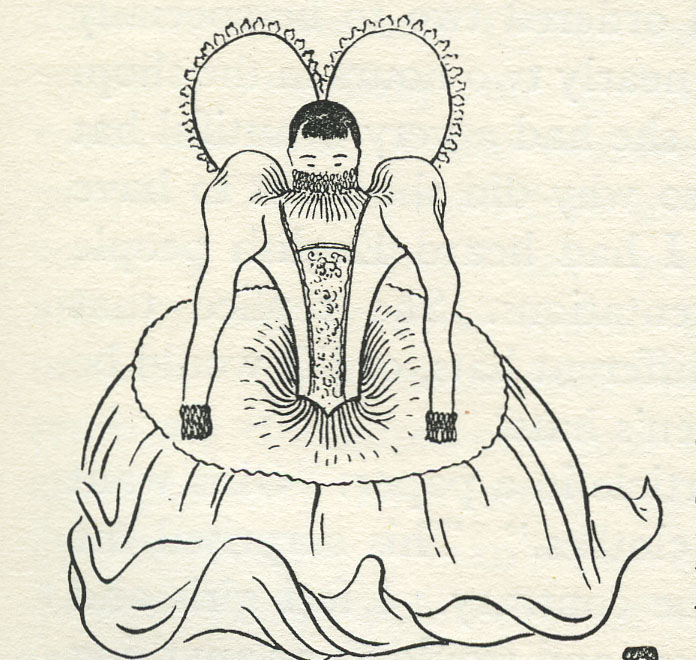

In each of his travelogues Chiang takes obvious pleasure in drawing the reader’s attention to the smaller details of life. He writes, ‘I am diffident of fixing my eyes on big things, I generally glance down at small ones. There are a great many tiny events which it has given me great joy to look at, to watch and to think about.’58 Describing the pleasure of London parks he writes, ‘I like to wander in London parks when it is windy, because I can see the quivering shapes of the tree-branches and the leaves being blown all in one direction or in confusion, producing a special sound very agreeable to listen to.’59 Such descriptions exemplify the sense of false naivety that often characterises the narrative of the Silent Traveller books, despite their positive attributes. This coupled with his generally flattering portrayal of Britain and his avoidance of more serious issues such as politics and the more unpleasant realities of life in early 20th century Britain lend the books a certain superficiality. However, Chiang does occasionally adopt a more critical tone, even if in a light hearted manner. In his chapter ‘On Women’, Chiang wryly remarks on the current fashion for wearing historic Chinese garments, among ladies of his acquaintance:

I was once struck by a lady who wore an old Chinese robe at a party. She was very proud of her gown… but I am inclined to wonder what English people would think of a small and short Chinese lady wearing an Elizabethan type costume picked up from the drawer of a repertory theatre. I can almost imagine the head of the lady would not even emerge from the huge skirt.’60

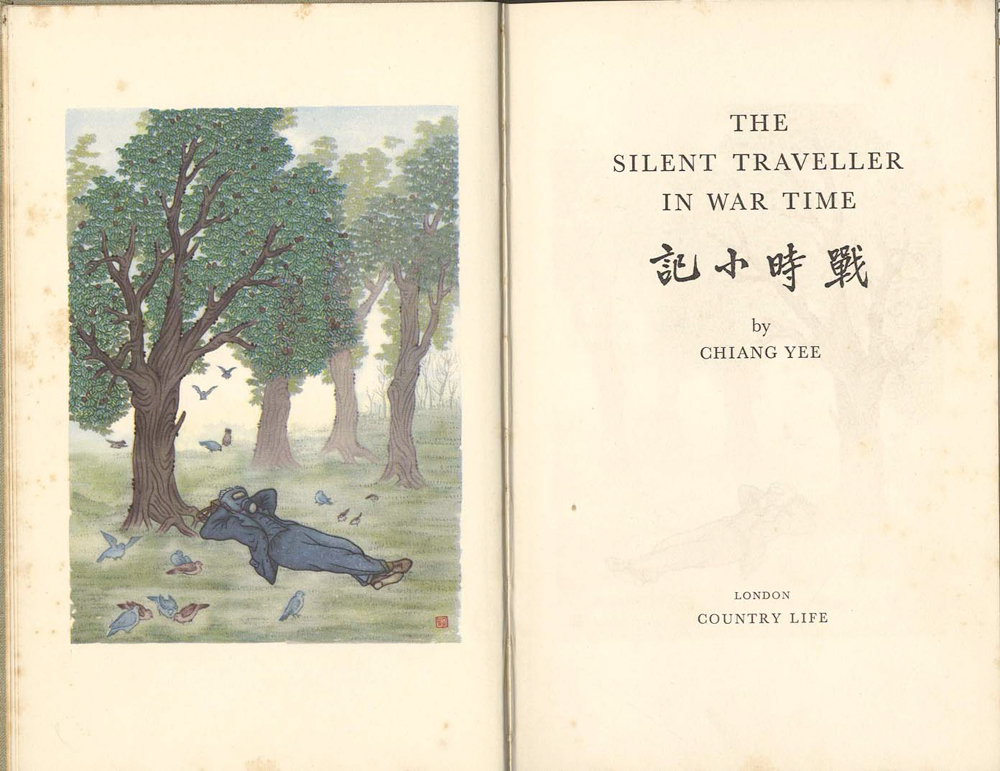

The Silent Traveller in War Time

War overshadowed Chiang’s life in Britain and had a profound effect on him, not least because of the outbreak of the second Sino-Japanese war in 1937, which wrought terror and violence throughout China, blighting the lives of his family and friends. He recorded the details of his own experiences of life in wartime London in his third Silent Traveller book, The Silent Traveller in War time, published in 1939.

The book is dedicated to his brother who was killed in the first months of the Sino-Japanese war and is poignantly written in the form of a letter to him. Despite the potentially distressing premise of this book, the narrative is upbeat and Chiang frequently describes scenes of beauty in his wartorn surroundings, such as silent shoals of barrage balloons drifting in the moonlit sky. The illustrations are a combination of paintings in newly colourful and naïve style and atmospheric monochrome ink paintings.

A Means of Escape

The Silent Traveller books offered readers the novelty of an ‘Orientalised’ view of Britain, coupled with a comforting account of familiar British landscapes, which provided gentle escapism during the dark days of the Second World War and the depression that followed it.

Although the travelogues are ostensibly about Britain, the narratives are interwoven with references to China, and reflections on Chinese cultural history and traditions. Consequently, the reader cannot forget that this view of Britain is that of ‘a homesick Easterner’. In this way, the Silent Traveller books represented, not only a new perspective on Britain, but also fascinating insights into Chinese life, culture and ways of seeing. In this excerpt from, The Silent Traveller in London, Chiang writes about the Chinese Mid-Autumn Festival: ‘It is supposed to be the birthday of the moon. At this time all the sweet-shops produce a great variety of seasonable cakes, which we call ‘Moon-Cake’… We generally have a specially good dinner on all festival days, and this certainly is no exception.’61

Although the Silent Traveller books present a charming, light-hearted personality intoxicated by his experiences of a new culture and eager to share his own, the narrative is pervaded by a sense of longing for home. It seems clear that as well as serving as an outlet for his creativity and a practical source of income, the Silent Traveller books also fulfilled Chiang’s own need for escape, from the realities of his difficult personal circumstances. Throughout his life in Britain, Chiang struggled with depression, anxiety, loneliness and the guilt of having abandoned his family, and his writing provided an opportunity to re-connect with the China of his past; untouched by the war by which it was being ravaged at the time he wrote these texts.62

Chiang discovered a successful literary formula in the Silent Traveller travelogues, and went on to write four more Silent Traveller titles about his travels in Britain, interspersed with other projects in the years leading up to 1954. (fig. 10) They simultaneously offered the appeal of the exotic and an antidote to equivalent Western accounts of China many of which, Chiang lamented, were based on scant evidence and experience of the country. He writes:

Many travellers who have gone to China for just a few months come back and write books about it, including everything from literature and philosophy to domestic and social life, and economic conditions. And some having written without having been there at all. I can only admire their temerity and their skill in generalising on great questions. I expect I suffer together with many others in the world, whose characters have been mis-generalised in some way.’63

This feeling of woeful misrepresentation provided the impetus for many of Chiang’s subsequent efforts to bring a better understanding of Chinese culture to the British public.

A Nationalistic instinct

Chiang’s autobiographical account of his childhood in China offers an intimate insight into Chinese life and culture. A Chinese Childhood (1940) details not only a personal history but a way of life that died out when modern social reforms were introduced to China. As such it is a valuable historical record as well as a fascinating account of Chiang’s early life. It is illustrated throughout with sketches and drawings, which accompany anecdotes and stories about life in China; from festivals and school life to food, clothes and hairstyles of the time.64

Presenting an accurate picture of China and Chinese experiences was central to much of Chiang’s work. In 1938, he accepted a short contract at the Wellcome Museum of medical history to work on displays of Chinese medicine, which he did on a part-time basis until 1940. During this time he curated several new displays on East Asian medical practice, and created instructive illustrations to accompany the objects. In his letter of acceptance for the post Chiang wrote:

I have been thinking of coming to do something for you as you suggested. I suppose you would like to make a proper show of Chinese exhibits in your museum, as you said yours is the first and best medical museum in the world, so it must be adequately arranged for the world appeal. We Chinese have suffered sometimes from the inadequate and not proper arrangement of our things in some museums in Europe. […] Therefore, this nationalistic instinct has driven me to accept your suggestion and I would like to do my best for you if possible.65

This letter clearly demonstrates Chiang’s concern to establish anauthentic representation of Chinese culture; to display Chinese artefacts in a proper context and as they were understood and used in China. In addition to satisfying his ‘nationalistic desire’ to accurately present Chinese culture, the job at the Wellcome Museum also represented much needed additional income for Chiang, especially as his teaching contract at SOS was not renewed after 1938. In 1941 the Wellcome Museum was hit by German bombs and the new displays that Chiang had created were sadly destroyed.66

Conclusion

Observant and articulate, Chiang Yee built a career on his knowledge of Chinese art and culture as well as his experiences as a Chinese exile in Britain. His books and lectures on Chinese art and culture gave much needed explanation and context to this then little understood subject, and signalled the beginning of a new era in which Chinese people were, for the first time able to represent their culture directly to Western audiences. The Silent Traveller books, with their alternative presentation of Britain, were an innovative attempt to synthesize two very diverse cultures at a time when the Orientalist model, characterised by a fictitious dichotomy between Occident and Orient, persisted as a dominant influence in the collective British consciousness.

The body of work that Chiang produced whilst living in Britain provides further interest when considered in the context of the emergence of the field of Chinese studies and Chinese art in particular; when imperialist frameworks established in the preceding century began, gradually, to be dismantled by more rigorous academic studies and presentations of China and Chinese culture, resulting in a noticeable shift in public attitudes towards China.

Through his activities as an artist, writer and educator Chiang played an active role in establishing a new era of cultural exchange between Britain and China, driven by the desire for improved scholarship and representation of Chinese art and culture as well as new commercial opportunities. Chiang was just one of a group of influential actors who contributed to this growing field of cultural interaction, but one who stands out for his unique approach to both literary and artistic projects.

Endnotes

-

Chiang’s pen name 哑行者‘ Ya Xing Zhe’was inspired by Confucian traditions of scholarly retreat, a practise associated with many of China’s best known painters and literati. Chiang elucidates his thoughts on this practise of scholarly retreat in: Chiang Yee. The Chinese Eye: An Interpretation of Chinese painting. London: Methuen, 1935: 70–72. In adopting this pen name Chiang clearly identified himself with this tradition, further enhancing the image that he cultivated for himself, as a modern literatus. ↩︎

-

Chiang Yee recorded his explorative journeys, initially around Britain and latterly in many other parts of the world including America, Australia and Japan writing a total of 12 Silent Traveller books during his life. ↩︎

-

Lin Yutang was one of the most influential Chinese writers and intellectuals in the first half of the 20th century. He moved from China to America in 1936 where he established himself as an eminent writer and essayist on the subject of modern China. His most famous works include My Country, My People (1935) and The Importance of Living (1937). ↩︎

-

Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010. Further research on Chiang Yee, in English includes: Huang, Suchen S. ‘Chiang Yee’, in Asian-American Autobiographers: a bio-bibliographical critical sourcebook, edited by Guiyou Huang. Greenwood Press, 2001; Janoff, Ronald. Encountering Chiang Yee: A Western Insider Reading Response to Eastern Outsider Travel Writing AnnArbor.MI, UMI Dissertation Services, 2002; Tzu-Chiu, Esther. Literature as Painting: A Study of the Travel Books of Chiang Yee. Masters Dissertation: University of Northern Colorado, 1976; Chen, Anna. Chinese in Britain. Seriesbroadcast on BBC Radio 4 in April/May, 2007. Chiang Yee is discussed by Diana Yeh (Keele University) in episode 8; Wright, Patrick. English Takeaway: Reflections on The Anglo-Chinese Encounter. Series of essays, Broadcast on Radio 3 in 2008. One episode is devoted to a discussion of Chiang and his work.Further sources on Chiang Yee’s life include:Chiang, Yee. Memoirs of a Chinese Childhood. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd, 1940; Chiang, Yee. China Revisited. New York: Norton, 1977. ↩︎

-

This region has strong associations with many of China’s best known artistic and literary figures including Li Bai (701–762) and Su Shi (1037–1101). Throughout his life Chiang felt the strong influence of this legacy and he attempted to model his own image and later career on the lives of China’s revered literati. He fondly reminisces about his hometown in many of his Silent Traveller books as well as in his memoirs. ↩︎

-

Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: 12–15. ↩︎

-

Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: 21–22. ↩︎

-

Correspondence between Innes Jackson and Chiang Yee, quoted in Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: 66. ↩︎

-

Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: 33–49. ↩︎

-

Sullivan, Michael. Art and Artists of Twentieth-Century China. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1996: 36. ↩︎

-

Ibid: 36 According to Michael Sullivan many Chinese students were sent to France after World War 1 ended in 1918, on the ‘diligent work and frugal study’ program, launched by Cai Yuanpei. ↩︎

-

British Museum.Chinese Diaspora in Britain. Accessed January 25, 2012. ↩︎

-

Chu Chin Chow was a popular musical comedy set in the Middle East, combining the two main locations and cultures at the centre of European Orientalist fantasies. The character after whom the show was named was a wealthy Chinese merchant and was one of the key ‘Chinaman’ caricatures of early 20th century Britain. The musical premiered in 1916 but its popularity saw it return to the London stage in 1940 and it continued to be performed throughout the war years. In The Silent Traveller in London Chiang recalls the influence of this musical on his own reception in London: ‘Four or five years ago I used to hear them (children) singing a chorus from the play Chu Chin Chow, when I passed them.’ In Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in London. London: Country Life, 1938:109. ↩︎

-

Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: 51, 57, 60. ↩︎

-

Liu Haisu was founder of the Shanghai Academy of Art. He was instrumental in introducing Western artistic practices not only into his own work but to that of his students in China; including life drawing and drawing from nature, which for many traditionalists at the time was seen as radical and controversial. ↩︎

-

Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in London. London: Country Life, 1938:151. ↩︎

-

Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: 59. ↩︎

-

Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: 57. ↩︎

-

Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: 53. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

An Exhibition of Modern Chinese Paintings and Fans by Chiang Yee. London: Mrs Betty Joel Gallery, 1936. ↩︎

-

Chiang, Yee. The Chinese Eye. London: Methuen, 1935:4. ↩︎

-

Sullivan, Michael. Art and Artists of Twentieth-Century China. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1996: 8–9. ↩︎

-

Clunas, Craig. ‘Oriental Antiquities/Far Eastern Art’. Postions east asia culture critique 2.2 (Fall, 1994): 324–326. ↩︎

-

In the introduction to The Silent Traveller in London (1937) Chiang recalls a comment made about him by a London critic which exemplifies this lingering imperialist attitude towards China and Chinese people. He writes, ‘As I am an Oriental (actually one of those strange Chinese people who “belong to an age gone by” as a London critic said of me) […]’. In Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in London. London: Country Life, 1938: ix. ↩︎

-

Pierson, Stacey. Collectors, Collections and Museums: the Field of Chinese Ceramics in Britain, 1560–1960. Oxford; New York: Peter Lang, 2007:115. ↩︎

-

Fry, Roger et al. Chinese Art: An Introductory Review of Painting, Ceramics, Textiles, Bronzes, Sculpture, Jade,etc. Burlington Magazine Monographs. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd., 1925:1. ↩︎

-

Stacey Pierson points out, many collectors and researchers were attracted to Chinese art by the Chinese tradition of art connoisseurship in the early 20th century and a small number were sufficiently proficient in Chinese language to be able to translate original texts on Chinese art and collecting practices. This fostered a more balanced reading of Chinese art compared beyond the more Euro centric surveys to the preceding centuries. S. W. Bushell, Percival David, Arthur Waley and Osvald Siren all translated and published Chinese texts on art and art collecting in English during the early 20th century. See Pierson, Stacey. Collectors, Collections and Museums: the Field of Chinese Ceramics in Britain, 1560–1960. Oxford; New York: Peter Lang, 2007:127. ↩︎

-

Waley was Assistant Keeper of Oriental Prints and Manuscripts at the British Museum from 1913–1929. He taught himself Chinese and Japanese and later devoted himself entirely to the study of Chinese and Japanese literature producing many translations throughout his life. ↩︎

-

Bickers, Robert. A. ‘“Coolie Work”: Sir Reginald Johnston at the School of Oriental Studies, 1931–1937’. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Third Series, Vol. 5, No. 3 (November, 1995): 387–9. Former naval medic and scholar of Chinese bronzes and Buddhist art, Walter Percival Yetts was the first to hold the lectureship in Chinese Art and Archeology at SOS. ↩︎

-

Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Chinese Art 1935–6. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1935. ↩︎

-

David,Sir Percival. ‘The Exhibition Of Chinese Art: A Preliminary Survey’. The Burlington Magazine, Vol.1, No.393 (December, 1935): 239. Quoted by Pierson, Stacey. Collectors, Collections and Museums: the Field of Chinese Ceramics in Britain, 1560–1960. Oxford and New York: Peter Lang, 2007:154. ↩︎

-

Stacey Pierson argues that despite the unprecedented collaboration with the Chinese government and the resulting range of objects on display, the exhibition ultimately represented a British interpretation or view of Chinese art. According to Pierson’s research, despite requests from the Chinese government that Palace museum staff should select the objects for the exhibition, David insisted that selections should be made by the British executive committee. ↩︎

-

Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: 60. ↩︎

-

Swedish art historian Osvald Sirénalso became another key contributor to the study of Chinese painting, writing in English in the first half of the 20th century. His major works on the subject include; The Chinese on the Art of Painting: Translations and Comments (1936), A History of Later Chinese Painting (1938) and Chinese Painting: Leading Masters and Principles (1956). Although their approaches were different, Sirén’s as an academic and Chiang’s as an artist, they both attempted to present a Chinese approach and understanding of Chinese painting to Anglophone audiences. ↩︎

-

Laurence Binyon became Keeper of Oriental prints and drawings at the British museum in 1913. ↩︎

-

Binyon, Laurence. ‘Painting and Calligraphy’. In Chinese Art, edited by Leigh Ashton. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co. Ltd, 1935:1. ↩︎

-

Chiang received significant assistance from Innes Jackson in refining his manuscript, which he acknowledges in the book. ↩︎

-

Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller: A Chinese Artist in Lakeland. London: Country Life, 1937: Preface. ↩︎

-

Binyon, Laurence. ‘The Chinese Eye: An Interpretation of Chinese Painting by Chiang Yee: Book Review’. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society No. 1 (January, 1937): 165–166. ↩︎

-

Chiang makes specific mention of Eumorfopolous’ attendance at his lectures in Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in London. London: Country Life, 1938:248. ↩︎

-

Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: 78–9, 118. Da Zheng notes the doubts expressed by BBC producers about Chiang’s accent and also lists the broadcasts Chiang participated in which included: ‘Another poet’s world’ (December 29, 1937). On which he talked about particular qualities of Chinese poetry and recited some works in Chinese (November 1937).‘The Northern Program’(11 February, 1938). A discussion of landscape around Lakes with a local farmer.‘Chinese Art’ on The Home Service BBCWAC (31 March, 1943). ↩︎

-

Including the Sunday Times National Book fair in 1937. He also supported several fundraising events organised by charitable organisations sending aid to China with lectures and painting demonstrations, including the Artists Aid China Exhibition, March 31-May 25, 1943 and various charitable events organised by Lady Cripps British United Aid to China fund throughout the late 1930s and 1940s. ↩︎

-

In the preface to his detailed biography of Chiang Yee Da Zheng notes the enduring relevance of this text which continues to be used as a standard text for college level calligraphy classes in North America see:Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: xx. ↩︎

-

Li, Ch’i. ‘Chinese Calligraphy by Chiang Yee: Book Review’. The Far Eastern Quarterly Vol.14, No.4, Special Number on Chinese History and Society (August, 1955): 578–579. ↩︎

-

London publishers signal books republished The Silent Traveller in London in 2001 and The Silent Traveller in Oxford in 2003 as part of their Lost and Found travel series. The Mercat Press in Edinburgh also republished the Silent Traveller in Edinburgh in 2003. Between 2009 and 2010 the Lakes, London, Oxford and Edinburgh books have been translated and published in China for the first time, by the Shanghai People’s Press. ↩︎

-

Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller: A Chinese Artist in Lakeland. London: Country Life, 1937: 3. ↩︎

-

Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller: A Chinese Artist in Lakeland. London: Country Life, 1937: 1–2. ↩︎

-

Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in Edinburgh. London: Methuen, 1948:2–3. ↩︎

-

Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller: A Chinese Artist in Lakeland. London: Country Life, 1937: Preface. ↩︎

-

Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in London. London: Country Life, 1938: xvi. ↩︎

-

Ibid: xvi-xvii. ↩︎

-

Chiang, Yee. The Chinese Eye: An Interpretation of Chinese Painting. London: Methuen, 1935:104. ↩︎

-

E.H. Gombrich cites Chiang’s painting ‘Cows at Derwent Water’, reproduced in The Silent Traveller: A Chinese Artist in Lakeland (1937), in his seminal text Art and Illusion, to support his thesis that the artist’s tendency is to ‘[…] see what he paints rather than paint what he sees’ in accordance with the artist’s own specific cultural idiom. For an in depth discussion on representation in art specifically citing Chiang Yee’s work see:Gombrich, E.H. ‘Part Three: Form and Function’. In Art And Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. London: Phaidon, 1960. ↩︎

-

**Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller: A Chinese Artist in Lakeland. London: Country Life, 1937: 32. ↩︎

-

Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: 74. ↩︎

-

Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: 72. Zheng writes that Markino’s book A Japanese artist in London (1910) was discussed at a meeting Chiang had with publishers Country

Life prior to the publication of The Silent Traveller: A Chinese Artist in Lakeland, but it is not clear from his discussion whether or not Chiang’s book was based on Markino’s or not. ↩︎ -

Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in London. London: Country Life, 1938: x-xi. ↩︎

-

Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in London. London: Country Life, 1938: 83. ↩︎

-

Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in London. London: Country Life, 1938: 220. ↩︎

-

Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in London. London: Country Life, 1938: 38. ↩︎

-

Chiang relates his grief and anxiety in a letter to Innes Jackson: Letter from Chiang Yee to Innes Jackson, 23 August, 1937 quoted in: Zheng, Da. Chiang Yee: The Silent Traveller from the East. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2010: 77. ↩︎

-

Chiang, Yee. The Silent Traveller in London. London: Country Life, 1938: x. ↩︎

-

This text continues to be a useful reference for scholars and researchers today and was recently referenced by Pauline Le Moigne in: ‘La symbolique auspicieuse des chapeaux populaires d’enfants en Chine’. In Costumes d’enfants :Miroir des grands: Hommage à Krishna Riboud: Exhibition catalogue, Musée Guimet, Paris, 20 October - 24 January 2011. ↩︎

-

Letter from the Wellcome collection archives relating to Capt. Johnston-Saint. File WA/HMM/ST/Lat/A41. ↩︎

-

Letter from Chiang Yee to Capt. Johnston-Saint, dated June 2nd, 1941; The Wellcome collection archives File WA/HMM/ST/Lat/A41. ↩︎