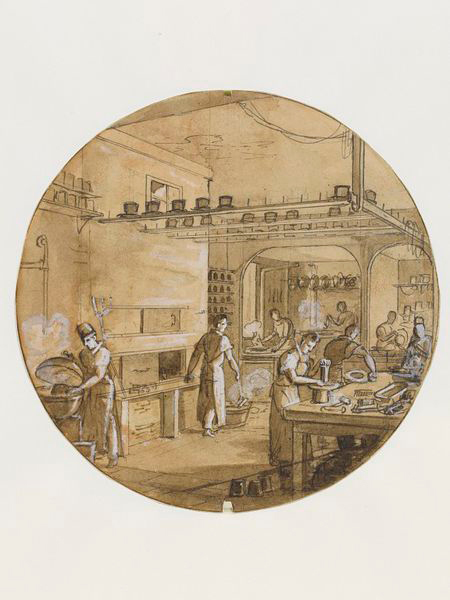

A small round print, La Chapellerie, depicting the inside of a Parisian hat-maker’s shop in the early 19th century, was recently acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum (fig. 1).1 This print is a rare survival, attesting to the production of a dinner service from which the finished wares have all but disappeared. Known as the Service des Arts Industriels (Service of the Industrial Arts), the dinner service was produced by the French porcelain factory, Sèvres, during the 1820s. Consisting of 180 pieces, the service represented 158 French technological crafts, from jewellery making to the processes used at the Sèvres factory itself. Painter Jean-Charles Develly both produced all the preparatory sketches and painted the wares by hand.

The history of the service is well known as a great deal of archival material survives at the Sèvres archives. It is likely to have been commissioned by Alexandre Brongniart, the then director of the Sèvres factory.2 Brongniart was interested in technology and chemistry and became a member of the jury for the Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie Française (Exhibition of French Industrial Products). The service was commissioned following the fifth Exposition, probably as a means of illustrating the Sèvres Company’s renewal as a beacon of the French luxury industries under his leadership – industries Brongniart had ample time to study as a juror for the Exposition.

This essay recontextualises the print acquired by the V&A within the production process of the Service des Arts Industriels. Drawn by Develly in 1828, La Chapellerie was created as the final outline for the decoration of a ceramic dinner plate. Measuring 13.9 cm in diameter, this round print was sketched in pencil, ink and chalk, on a paper base. There are two U-shaped notches at the top and bottom of the drawing, visible from the front and the back. The composition of the drawing is simple and efficient. The eye is drawn into the central part of the drawing, to the back of a male figure steaming a top hat. This single figure in an uncluttered space invites the viewer to then peruse the workshop. Framing this central element, two stages of production are shown – steaming and curling. The background of the drawing is less detailed, but the hats littering the shelves on the back wall and the racks overhead, full of finished products, leave no doubt as to the nature of the workshop.

A long process of research, multiple preliminary sketches, and a number of firings culminated in the finished product. Having initially researched whatever craft he wished to depict, Develly would then try to draw all the different stages of production into one composite sketch – as we can see in La Chapellerie. While the naturalistic rendering of the drawing might suggest that it was an accurate depiction of a working space, Develly cleverly combined various stages into one – synthetic – setting. This method was advocated and encouraged by Brongniart, who said himself: ‘In the centre of each plate has been reproduced, in a picturesque but accurate way, the principal operation of our industrial art, by combining in the same workshop the largest number of operations possible.’3

Once this final sketch was completed, its outline was transferred to a white porcelain plate, which had already been gilded at the appropriate places. The back of the drawing was covered in graphite – of which traces remain on the reverse of La Chapellerie. The U–shaped notches in the paper, observed above, mark the space where hooks were used to attach the paper to the plate. By tracing the drawing with a sharp tool, its outline in graphite was transferred to the porcelain plate. Develly’s artistic process then culminated in his hand painting the plate following the graphite outline before it was fired for the first time.4

This first stage in firing was called the ébauche. Historian Pierre Ennès published a list of firings for the entire service, assembled from the archive of the Musée National de Céramique-Sèvres. The ébauche for La Chapellerie took place on the 5th of June 1828.5 The plate then had its finishing touches applied (retouche) and was fired one final time, on the 2nd of August 1828.6

The current location of the plate is unknown, as is that of most of the service. Indeed, apart from four plates in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, there are very few examples in museums of finished wares from the service.7 The V&A’s La Chapellerie may be the only visual record that remains of an object, but is also a testament to that object’s production.

Endnotes

-

Victoria and Albert Museum, Museum no. E.287-2011. ↩︎

-

Tamara Préaud, ‘Brongniart as Administrator,’ in The Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory: Alexandre Brongniart and the Triumph of Art and Industry, 1800-47, ed. Derek E.Ostergard (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997), 43–53. ↩︎

-

Quoted in Marcelle Brunet, Sèvres: des Origines à nos Jours (Paris: Office du Livres, 1978), 211. ↩︎

-

Pierre Ennès, ‘Four Plates from the Sèvres “Service des Arts Industriels” (1820-1835),’ Journal of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 2 (1990): 89–106. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

These four plates are viewable online via the following links:

www.mfa.org/search/collections?accessionnumber=65.1908

www.mfa.org/search/collections?accessionnumber=65.1909

www.mfa.org/search/collections?accessionnumber=65.1910

www.mfa.org/search/collections?accessionnumber=65.1911 ↩︎