Abstract

Recent examination under ultraviolet light of the drawing, Study for the head of an Angel in the Dome of the Château de Sceaux, by Charles Le Brun (1619-90), enabled an inscription to be deciphered, revealing the drawing’s early provenance. This newly legible inscription stands as a tantalising reminder of two distinguished collectors: the French connoisseur, Jean Paul Mariette (1694-1774), and eminent furniture designer André-Charles Boulle (1642-1732).

In 2008, as Assistant Curator in Prints and Drawings, the author was asked to examine the inscription on the mount of a drawing by Charles Le Brun (1619-90), entitled Study for the head of an angel in the Dome of the Chapel at the Château de Sceaux (V&A D.1103-1900). Examination of the inscription under ultraviolet light revealed previously hidden details of its early history and provenance as a collector’s piece (fig.1). This investigation was part of the preparatory work for a major project documenting the collection of Pierre-Jean Mariette, which resulted in the publication of a comprehensive catalogue.1 The discovery of this information presents an opportunity to consider the development, and nature, of the collecting of drawings between the end of the 17th and middle of the 18th centuries in France.

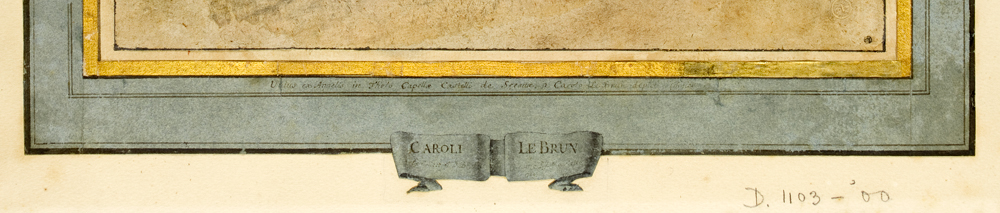

The drawing, in black, red and white chalk on light brown paper, shows the upturned head of an angel. It is one of several surviving studies that Le Brun made for the decorative scheme of the chapel of the Château de Sceaux, begun in 1674 for the French Minister of Finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert.2 In the bottom right-hand corner of the sheet is the collector’s mark, ‘lugt 1852’. This is the collector’s mark of Pierre-Jean Mariette (1694-1774), arguably one of the most significant art collectors of the 18th century.3 The blue card mount, with a gilded band surrounding the drawing, in turn framed by ruled lines, and a cartouche drawn in pen and ink at the lower centre, is also characteristic of Mariette (fig.2).4 The connoisseur devised these cartouches to allow for inscriptions giving further information about the work. This Le Brun drawing is inscribed three times: two are visible and a third invisible to the naked eye.

Most of the inscription in the cartouche of D.1103-1900 is now faded. Barely visible, the first reads: ‘Ex Collectione D. Boulle nunc P. J. Mariette 1739’. This is in the same hand as the second inscription within the lower framing lines of the mount, which reads: ‘Upius ex Angelis in Tholo Capellae Castelli de Sceaux a Carole Le Brun depict […illegible]’ (‘Head of an Angel from the ceiling of the chapel at the Château de Sceaux’). As it is difficult to read this inscription in visible light, or with the naked eye, it was first examined under infrared light. The long wavelength of infrared light shows up carbon-based inks. The inscription could not be seen under infrared light, establishing that it was not written in a carbon-based ink. As a result, we looked at it under a microscope. Further traces of the inscription could be seen, however it was still barely legible. It was then examined under ultraviolet light. The shorter wavelengths of ultraviolet light make iron-based ink appear darker and therefore legible. This revealed an earlier inscription, which reads:

CAROLI LE BRUNEx Collect ot A.C. Boulle Aunc P.J. Mariette 1739

(Charles Le Brun From the Collection of André-Charles Boulle now in that of Pierre-Jean Mariette 1739).5

All three inscriptions are in the same hand, presumably that of Pierre-Jean Mariette. The presence of an earlier inscription is intriguing, particularly as Mariette changed the provenance details from André-Charles Boulle to D. Boulle, who, according to Pierre Rosenberg, was an heir of André-Charles Boulle. Provenance details of other works in his collection were not always recorded by Mariette, suggesting that he may not always have had access to such information. However, considering that Mariette frequently attended sales as well as meeting and corresponding with fellow collectors, this seems surprising. In this case, ultraviolet light has revealed a change of thought by the connoisseur in recording the provenance history of a particular work.

Perhaps Mariette acquired the drawing early in his career and wanted to bolster the status of his own collection by linking it to the highly esteemed collector, André-Charles Boulle. This earlier inscription, placed in the lower centre of the mount, is likely to have suffered more abrasion than the others when being handled, resulting in its fading. The need to renew the inscription may have occurred at a time when Mariette had become established as a connoisseur and therefore felt less need to link his own collection directly to one of the great collectors of the previous generation. After all, if D. Boulle was a descendent of André-Charles Boulle, Mariette’s new inscription still traces the drawing back to the collection of the Ebéniste du Roi.

André-Charles Boulle (1642-1732) was perhaps the most important furniture designer working at the turn of the 18th century. He was employed by Louis XIV (1638-1715) on numerous projects. In 1672, he received the title Ebéniste, Ciseleur, Doreur et Sculpteur du Roi, along with the royal privilege of lodging in the Galleries du Louvre.6 Boulle was also an avid collector of prints and drawings and amassed many drawings by Le Brun during his lifetime. In the inventory compiled by Boulle in 1720, following a fire in his workshops, he claims to have amassed a collection of thousands of prints, drawings and paintings.7 His passion for collecting frequently landed him in debt. In his Abécédario, Pierre-Jean Mariette notes that, ‘no sale of drawings or prints took place […] at which he [Boulle] did not make frequent purchases without having the means to pay’.8 These were sold, along with his entire collection, by Boulle’s heirs, in order to pay off the debts he left on his death in 1732.

Mariette became involved with Boulle’s collection of prints and drawings when he was commissioned to catalogue and value it for the sale inventory, a value he put at 7,622 livres.9 Perhaps testament to the furniture designer’s connoisseurial eye, the sale of his collection actually achieved 14,914 livres, almost twice as much as the estimated value.10 The 1732 inventory provides an insight into Boulle’s taste. The Italian school is represented by several portfolios of mixed works from 16th-century artists including Raphael (1483-1520), Giulio Romano (1499-1546) and Tintoretto (1519-1594), while there are entire portfolios of drawings by 17th-century artists, including Guercino (1591-1666) and Annibale Caracci (1560-1609). Although there are fewer works from the Flemish school, leading artists of the 17th century, including Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641), are listed.

After the Italian school, the collection is strongest in its holdings of 17th-century drawings of the French school. For example, the inventory lists seven portfolios of drawings by Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), eleven by Pierre Corneille (1601/03-1664), and ten by Le Brun.11 Most of the artists listed from the French school are contemporaries of Boulle. Jean-Baptiste Corneille (1649-93) worked predominantly in Paris, while the Flemish artist Adam Frans van der Meulen (1632-90), along with Le Brun and Boulle, was in the service of King Louis XIV. It is possible that Boulle acquired some of these drawings directly from artists who were also working for the court.

None of the drawings by Le Brun in the Boulle inventory are identified as works for the Château de Sceaux, but then, throughout the inventory, very little information is given for each item, the description of which focuses on groupings of types, rather than the projects to which they relate. This makes identifying specific drawings very difficult. Considering the categorisation employed in the inventory, the V&A drawing (D.1103-1900) may have been part of item number 48, valued at 60 livres, which is described as: ‘A small portfolio without ties of original drawings by Monsieur Lebrun of studies, figures, heads and other subjects.’12

Mariette gave varying valuations for Drawings by Le Brun listed in the inventory. The lowest is six livres, for item 45, a portfolio of ornamental designs and tapestry borders for the Hôtel de la Bazinieres. The highest is for item 110, described as a portfolio of drawings for sculptures and history subjects, all by Le Brun, valued at 100 or more livres.13 A similar range of valuations was given to drawings by Le Brun’s contemporaries, van der Muelen and Poussin, both strongly represented in the 1732 inventory. Item 71, ‘a packet of drawings including some by Poussin’, was valued at 3 livres, while 60 livres was given for item 93, described as a portfolio containing history subjects by the same artist. Van der Muelen’s drawings ranged in value from eight livres, for item 57, a portfolio of figure studies, to 100 livres, for item 59, a portfolio of studies of towns in watercolour. Items by other artists, including item 8, a portfolio of drawings by Pierre Corneille, item 17, drawings by Callot (1592-1635), and item 22, which includes numerous drawings by Gaspar van Wittel (1652-1736) and Bartolomé Estaban Murillo (1618-1682), were also given high valuations, of 150 livres, in the inventory.

With such brief descriptions of each portfolio, interpreting Mariette’s valuations is difficult. In some cases, such as item 71, including drawings by Poussin, the small size of the lot and limited number of drawings by the renowned artist, supports the low valuation of three livres. While subject and project are not specified, Mariette takes care to note whether drawings are by the artist or their studio. Item numbers 22 and 25, which include 108 drawings of landscapes by Murillo, 109 by van Wittel, and various coloured drawings by Pierre Monier (1641-1703), are each valued at 150 livres, and appear to have been of a considerably larger size than other inventory items.

The subject does not appear to have had a bearing on the valuations in the inventory. Items 24 and 25 are landscapes, while item 59 lists city views by van der Meulen, and item 110 includes designs for sculptures and history subjects by Le Brun. Considering Marriette’s reputation as a connoisseur, it seems most likely that valuations were given on the basis of the number of original drawings by the artist listed in each lot as well as their quality.

The inscription on the V&A drawing (D.1103-1900) states that it entered Mariette’s collection in 1739, seven years after the Boulle sale, strongly suggesting that the drawing had passed into another collection prior to its acquisition by Mariette. The provenance of works was clearly something that interested Mariette, who recorded such details onto the distinctive mounts made for the drawings in his collection. Mariette gathered much of this information on provenance by attending auctions in Paris.14 His reputation as a connoisseur and dealer, along with his friendship with other amateurs, brought him further opportunities to visit and view drawings in private collections. Having valued the Boulle collection in 1732, he would have been well aware of the provenance of D.1103-1900. Yet Mariette chose to give only details of the Boulle provenance and not that of the collection from which he acquired the drawing in 1739 (unless of course it was acquired by D. Boulle in 1732 and retained by him for the seven intervening years). Perhaps Mariette was selective about which collections he recorded on his mounts. By naming Boulle, who worked with Le Brun for Louis XIV, Mariette strengthened the attribution to that artist, as well as the identification of the study as a preparatory sketch for the Château de Sceaux.

The sale catalogue compiled on Mariette’s death lists 1,466 loose and mounted drawings from the French school. As with the 1732 inventory of Boulle’s collection, the Sale catalogue for Mariette’s collection rarely identifies specific drawings, giving instead generic descriptions to groupings of works.15 Thirty-two drawings are listed as being by Charles Le Brun, including two further studies for the ceiling of the chapel at Sceaux (now in the Louvre).16 The study for the head of a cherub (inventory number 27 716) is inscribed on the mount as coming from the collection of D. Boulle and relating to the decoration at Sceaux; the study for a head in profile (inventory number RF 2372) gives no details of provenance or subject, but only identifies it as a work by Le Brun (fig. 3 and 4). Taken together, these two studies and the inscription on D. 1103-1900 reveal that Mariette was collecting drawings by Le Brun related to the same project, from a variety of sources.17 On both drawings with a Boulle-family provenance (V&A D.1103-1900 and Louvre 27 716), Mariette inscribed the details of the related project on the mount, suggesting he was aware of the relationship of these drawings to Sceaux, and it may be that this information was noted by André-Charles Boulle or his heir.

Mariette’s collecting practices reflected contemporary attitudes to the importance of drawings. During the 18th century, connoisseurship was developing in Europe; drawings were praised by contemporary theorists as offering a uniquely revealing means to study the formation of an artist’s individual style and working process.18 In his introduction to the Crozat sale catalogue of 1750, which was to cement Mariette’s reputation as a connoisseur, he wrote that ‘in a drawing, refined and enlightened eyes discover the whole of the master’s mind’.19 The practice of presenting drawings within bespoke mounts was first introduced in the 16th century by the artist and biographer Giorgio Vasari (1511-74) and copied by 18th-century connoisseurs, who inscribed their mounts with details of both artist and scheme in Latin.20 In addition to the practical purpose of protecting each drawing, these mounts created a framework for presentation and interpretation.21 Mariette’s signature mount combines line and colour to focus our attention on the work.22 His use of the mount to record details of previous ownership, following the practice first introduced by Vasari, reflects his particular interest in provenance. These inscriptions, contained in cartouches drawn on the mount in pen and ink, along with ruled lines enclosing a gilded frame, become an intrinsic part of the visual object. The presentation, along with the choice of Latin for the inscription, effectively elevates its status from a working drawing to a finished work of art and object for study.

Examination of the drawing itself reveals how much care was taken in displaying the object. Before being mounted, paper was added to the lower corners of the page, making it uniform in shape, while extending the drawing to include the shoulders of the angel on either side of its neck (fig.5), a practice typical of Mariette, who often enlarged drawings in such a manner.23 It is, however, possible that this restoration was made by Boulle, following damage incurred during the fire in his workshops in 1720, or by an intermediate owner of the drawing prior to its acquisition by Mariette. This intervention, combined with the frame of the mount, makes a complete image, or ‘finished work of art’, and creates a drawing that would be more acceptable for the 18th-century connoisseur to study and to sell.

On the portion of paper that extends the drawing in the lower right corner, is Mariette’s recognisable collector’s mark: an ‘M’ contained within a circle. The practice of using such marks to document collection history was just beginning to evolve in France.24 Mariette is known to have been selective about the drawings to which he added his collector’s mark and always placed them in the lower portion or least valuable part of the sheet.25 As Barthélemy-Labeeuw has observed, this choice of position is common to Mariette’s documentation practice as it does not detract from our experience of reading the drawing.26

Conclusion

The Study for the head of an angel in the Dome of the Chapel at the Château de Sceaux was acquired by Mariette at a time when the collecting and studying of master drawings was evolving. The presentation of the study, extended either side of the angel’s neck, stamped with his collector’s mark, mounted and labelled, reflects contemporary ideas about connoisseurship and documentation, of which Mariette was a driving force. Mariette’s practice of mounting drawings and annotating these mounts with details of artist, subject, and collection, shows a developing tendency to individualise works of art. This distinguishes Mariette’s practice from that of grouping works together with little description, as was common in art sales of the time, including the posthumous auction of his own collection as well as that of Boulle. Indeed, the fact that Mariette himself catalogued Boulle’s collection shows that his documentation practices changed over the course of his career as a collector. Commonly employed in the analysis of paint pigments and in identifying recent restorations on paintings, the use of ultraviolet light in the examination of drawings is more unusual. In the case of D.1103-1900, it has revealed significant information on the early provenance of this work.

Technical advances in the examination of works such as that of the Le Brun drawing will hopefully continue to aid future investigations into drawings and their importance in early collections formed by figures such as Boulle and Mariette. Such investigations have the capacity to change the way we think about works of art and the collections of which they form a part, revealing new information about collecting and connoisseurship in the 18th century.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my colleagues in the Conservation Department at the V&A, in particular the late Merryl Huxtable, Alan Derbyshire and Sophie Connor, for their invaluable support and technical insight, which has been crucial in researching this article.

Endnotes

-

Examination of the drawing was carried out by the V&A in conjunction with research for Pierre Rosenberg’s monograph on Mariette’s collection, the first volume of which was published in 2012. See Pierre Rosenberg, Les dessins de la collection Mariette: École française, vol. II (Milan: Electa, 2012), 834, no. F.2253. ↩︎

-

Lydia Beauvais, Charles Le Brun 1619-1690: Inventaire général des dessins École Française, vol. I (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2000), 62. ↩︎

-

Frits Lugt, Les Marques de Collections de Dessins & d’Estampes: Marques estampillées et écrites de collections particulières et publiqes. Marques de marchands, de monteurs et d’imprimeurs. Cachets de vente d’artistes décédés. Marques de graveurs apposées après le tirage des planches. Timbres d’edition etc. (San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1975), 331. ↩︎

-

For discussions of the mount used by Mariette, see Sue Welsh Reed, ‘The Mariette Sale Catalogue,’ in La vente Mariette: Le catalogue illustré par Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, ed. Pierre Rosenberg (Milan: Electra, 2011), 37-45; see also Kristel Smentek, ‘The Collector’s Cut: Why Pierre-Jean Mariette Tore up His Drawings and Put Them Back Together Again,’ Master Drawings 46, no.1 (2008): 36-61, see in particular 38-40, for Smentek’s discussion of the format and appearance of the mounts devised by Mariette for his collection of drawings. For more recent scholarship on Mariette’s collecting practices see Laure Barthélemy-Labeeuw, ‘La collection de dessins de Pierre-Jean Mariette (1694-1774): sa vente après décès, sa marque, ses montages,’ in Les marques de collection, vol. I, ed. Peter Fuhring (Paris: Société du Salon du dessin and Dijon: L’Echelle de Jacob, 2010), 106-7. ↩︎

-

This inscription has recently been published in Rosenberg, Les dessins de la collection Mariette: École française, 834, no. F.2253. ↩︎

-

Eleanor John, ‘André-Charles Boulle,’ in The Grove Dictionary of Art, vol. 4, ed. Jane Turner (London: Macmillan Publishers Limited, 1996), 531. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 531; see also Jean-Pierre Samoyault, André-Charles Boulle et sa famille: Nouvelles recherches: Nouveaux documents (Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1979), 8-10. ↩︎

-

John, ‘Andre-Charles Boulle,’ 531. ↩︎

-

Samoyault, André-Charles Boulle et sa famille, 98; see also Welsh Reed, ‘The Mariette Sale Catalogue,’ 37-45. This valuation is conservative in comparison to Boulle’s valuation of his own collection at 217,200 livres twelve years earlier, following the loss of works in a fire. However, it must be remembered that this earlier valuation was made with the intention to prompt the King to offer an allowance that would cover the loss of these works. ↩︎

-

Samoyault, André-Charles Boulle et sa Famille, 8. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 98-135. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 124 (‘Un petit portefeuille sans cordons de dessins originaux de Mr Lebrun d’etudes, figures, testes et quelques sujets…’). ↩︎

-

Ibid., 12-15. ↩︎

-

Jean Cailleux, ‘Apud Mariette et Amicos,’ The Burlington Magazine 109, no.773 (August 1967): i-vi. ↩︎

-

Laure Barthélemy-Labeeuw lists 24496 Italian, 548 Dutch and Flemish, and 1466 French loose and mounted drawings, and 953 Italian, 194 Dutch and Flemish and 2697 albums of drawings in ‘La collection de dessins,’ 100; see also François Basan, Catalogue raisonné des différens objets de curisosités dans les sciences et arts, qui composoient le cabinet de feu M. Mariette (Paris: Chez G. Desprez, 1775), Ix. ↩︎

-

Basan, Catalogue raisonné, 180. The drawings by Le Brun are divided into six lots (Lots 1178 to 1183). In the description of these lots, no works are identified as being studies for the chapel at Sceaux. However, a number of lots, 1180 and 1182, list different subjects (divers autres sujets), and it may be that D.1103-1900 was grouped amongst these drawings. ↩︎

-

For Louvre inventory numbers 27 716 and RF 2372, see Rosenberg, Les dessins de la collection Mariette: École française, 833, no. F.2252 and 834, no. F.2253. See also Beauvais, Charles Le Brun 1619-1690: Inventaire général des dessins, École française, 64, cat.103, inventory number 27 716 and 70, cat.130, inventory number RF 2372. Inventory number 27 716 is inscribed on the mount by Mariette: Chérubim in Tholo Sacrarii castelli nuncupati de Sceaux a Carolo Le Brun depicti, effigie; Caroli Le Brun ex collect. Ol. D. Boulle, nunc P. J. Mariette 1739, documenting acquisition from another member of the Boulle family. Mariette has not inscribed the provenance of the drawing on the mount of inventory number RF 2372. ↩︎

-

Jennifer Tonkovich, Jean de Julliene: collector & connoisseur (London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2011), 31. ↩︎

-

Pierre-Jean Mariette, Description sommaire des statues figures, bustes, vases, et autres morceaux de sculpture, tant en marble qu’en bronze: & des modèles en terre cuite, porcelaines, & fayences d’Urbin, provenans du Cabinet de feu M. Crozat: dont la vente se fera le 14 décembre 1750 & jours suivans, en l’hôtel où est décédé M. le marquis du Châtel, rue de Richelieu (Paris: Chez Louis-François Delatour, 1750), iii. ↩︎

-

Pierre Rosenberg, La vente Mariette: Le catalogue illustré par Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, (Milan: Electra, 2011), 38; see also Catherine Monberg Goguel, ‘Vasari’s attitude towards collection,’ in Vasari’s Florence: Artists and Literati at the Medicean Court, ed. Philip Jacks (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 111-4. ↩︎

-

Barthélemy-Labeeuw, ‘La collection de dessins,’ 106-7; See also Carlo James et al., Old Master Prints and Drawings: A Guide to Preservation and Conservation, trans. & ed. Marjorie B. Cohn (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1997), 151. ↩︎

-

Kristel Smentek discusses this in detail, comparing the theories of Mariette and the portrait painter, writer and collector Jonathan Richardson, the elder (1667-1745), amongst others; see Smentek, ‘The Collector’s Cut,’ 36-7. ↩︎

-

Smentek discusses that Mariette frequently enlarged drawings within his collection; see ‘The Collector’s Cut,’ 40. ↩︎

-

Tonkovich, Jean de Julliene: collector & connoisseur, 41. ↩︎

-

Welsh Reed, ‘The Mariette Sale Catalogue,’ 37-45; See also Laure Barthélemy-Labeeuw, ‘La collection de dessins’ 105. ↩︎

-

Barthélemy-Labeeuw, ‘La collection de dessins de Pierre-Jean Mariette (1694-1774),’ 104; see also M. Dominique Le Marois, ‘Les montages de dessins au XVIIIe siècle: l’exemple de Mariette,’ 87-96, Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français (1982): 88. ↩︎